Creating a "Nostalgic Future" with Digital Fabrication ~ Yuka Watanabe, Representative of Fab Lab Kamakura

Watanabe Yuka

Fab Lab Kamakura

The rapid spread of 3D printers has led to visions of a future where every household has one. This technology, which creates various objects from digital data, is called digital fabrication or personal fabrication and is a cutting-edge field attracting attention in IT. Fab Lab Kamakura, a pioneer in this field, also draws attention for its uniqueness, operating out of a building converted from an old storehouse. This time, we spoke with Yuka Watanabe, who heads Fab Lab Kamakura.

(Interviewer: Yuzo Ono, Planning Promotion Department Manager, Dentsu Digital Inc. Business Bureau)

Photo by FabLab Kamakura

Next-generation infrastructure that unlocks individual talent and proposes new ways of working

──How did you first encounter digital fabrication?

Watanabe: I first encountered it around 2011 when I co-founded Fab Lab Kamakura with Hiroya Tanaka, then an associate professor at Keio University. Having worked in urban planning after graduating from university, I approached digital fabrication more as a system than a personal desire to create something. I sensed it could become the infrastructure of the next era, and that this infrastructure would transform how people work.

I myself had a period of being bedridden after an accident. During that time, I realized anew that I could do almost anything using the internet and technology without even leaving my home. Technology can be a solution. For example, designers are often extremely busy, frequently working all-nighters or having to sacrifice family time. It would be wonderful if there were alternatives to quitting their jobs in such situations. I believe digital fabrication can propose new ways of working. Right now, I am my own test subject.

──So you became interested in digital fabrication as infrastructure, rather than just making things.

Watanabe: That's right. Also, it's fascinating to see how people's thinking and behavior change. In architecture and urban planning, I've focused on how people interact with space, how they transform, and how that revitalizes a place. But when space becomes too localized, everything, including human relationships, inevitably starts to contract. The boundlessness of digital creates a sense of openness. It's not just the people who come to participate in the Fab Lab who change; we, the ones running it, change too.

──What were your initial impressions when you first saw a 3D printer?

Watanabe: I thought it was amazing. That moment when zero becomes one creates a strange, profound emotion. I don't know why, but it moves me every single time.

──Fab Lab Kamakura has undertaken various initiatives over the years. Which ones stand out most to you?

Watanabe: My top pick is definitely the "Fujimock Festival." With the theme "The Forest in Our Daily Lives," participants experience thinning in the hinoki cypress forests at the foot of Mount Fuji. Then, under professional guidance, they use that wood to create items like cutting boards and sake vessels through digital fabrication. It connects the forest to the kitchen via digital technology, bringing nature and the forest into daily life. We spend half a year preparing for this, and then we party (laughs).

Another area we're focusing on is education. The word "education" comes from Latin: "e" means "out," and "ducation" means "to draw out." It's said to also imply drawing out talents dormant within a person. Using digital fabrication as a catalyst to draw out individual talents, serving as a trigger to guide them to the right place for them—and if that sparks various chemical reactions, that would be wonderful.

──Fab Lab Kamakura is located in the historic town of Kamakura, and I find it unique that the building itself utilizes an old storehouse. Is there a particular reason behind that choice?

Watanabe: I've personally researched the relationship between renovation and art projects. Rather than scrap-and-build, I believe in finding new interest by changing the context of existing things and utilizing past memories. Kamakura is a city where there's already a shared understanding about blending old and new. As a Fab Lab, we can also rapidly generate solutions.

For example, we're working on an initiative to pass down traditional techniques, like the construction methods of the old storehouse we're currently using, through digital technology. This storehouse was actually originally in Akita; we dismantled it, reconstructed it here, and updated it with new elements. What strikes me as futuristic is how we color-scan the earthen walls to reproduce their hues for painting. The paint shop blends colors from this scan data to recreate them. Despite operating in a space about the size of a 4.5-tatami-mat room, they can produce over 3,000 colors on the spot. Since they store color information as digital data, they can create the exact same paint color within 30 minutes just by receiving a phone call. This approach of utilizing only data without holding inventory is truly remarkable.

In this way, when tradition is updated through digital means in various forms, it becomes more accessible to modern life. If ordinary people can incorporate it as a subtle accent, then tradition won't fade away. As laser cutters and 3D printers become more widespread, I believe such initiatives are what make Japan appear attractive on a global scale. Sometimes I view Japan with the perspective of an international student. The techniques, the depth, the sheer Japanese craftsmanship is truly remarkable. I hope we can embrace this as a new material, leading to a renewed appreciation for the brilliance of our ancestors.

Rediscovering the joy of making, recycling resources within the home—an old yet new future

──Co-founder Tanaka once said, "Personal fabrication means reinterpreting the spirit of the era before mass production through a modern lens and updating it for today's technological environment." I deeply resonated with this perspective of reevaluating mass production and bridging the spirit of the past to the present. Indeed, I believe making things was a far more enjoyable activity in the era before mass production.

Watanabe: We call it a "nostalgic future." It's like being able to make a chair with the same feeling as baking a birthday cake. Adding the option to "make" even small things gives a sense of returning to a time not so long ago. Many people who come to Fab Labs are involved in manufacturing at large corporations but feel disconnected from actually creating something. They come to Fab Labs to resolve that sense of unease.

──I think the term "personal fabrication" carries a nuance in the "personal" part, suggesting that individuals are reclaiming a significant power that was previously only held by large organizations.

Watanabe: Exactly. In today's consumer society, the barrier to making things is high, and it's disconnected from daily life. But if you want something simple, like a small hook to hang something here in your house, you can make one that's just the right size in about ten minutes with a 3D printer. Mass production is convenient and will remain a necessary option, but personal fabrication is about fulfilling those small, "I wish I had this" needs. It doesn't conflict with large corporations.

When you actually see it finished, it's incredibly moving. It gives you this deeply satisfying feeling—it's kind of like learning how to pickle umeboshi, you know? (laughs) And having that extra option makes you feel a bit freer.

But the impact this has on individuals is quite significant. Something shifts dramatically within them, and their thinking becomes more positive. I believe that when this reaches a certain critical mass in society, it could become a tremendous force. I'm thrilled to be living in an era where such small innovations create big waves, and I'm incredibly curious about what services will be introduced next and how they'll radically transform society.

──Mass production also leads to mass disposal, but digital fabrication carries a strong awareness of environmental considerations, right?

Watanabe: We're having ongoing discussions about turning waste into resources. The conventional mindset is to discard things when they break, but imagine if you could put them in a special box and they turned into something like multi-purpose powder. Then, if you could use that powder as material to print something new with a 3D printer, the very concept of objects would change. Today it's a bowl, tomorrow it becomes a hanger—things would persist by changing form. Such cycles would become commonplace, circulating within homes, leading to a society where waste doesn't exist in the first place. That's the future we envision. We often say the 21st century is the era of materials. There are naturally derived ones, and it would be fascinating if a universal material emerged. For instance, glass is already practically used as a 3D printer material—it's incredibly beautiful and can be melted down and reused.

──It's wonderful to imagine things circulating within the home without producing waste. Like not needing to buy new shoes as children grow, but gradually resizing them instead (laughs).

Watanabe: With sweaters, you can unravel them and reknit them, right? The number of molecules on Earth remains constant; on a planetary scale, even earthquakes and volcanic eruptions don't change it much. I think it would be great if we could achieve that within our homes. Frankly, if we keep discarding things at this rate, it'll lead to serious problems, so I believe we should start sooner rather than later.

The "Earth People" and "Wind People" Supporting Digital Fabrication

──What's the situation overseas?

Watanabe: Spain and the Netherlands are about five years ahead of Japan. They're already rapidly advancing the digitization of urban planning and lifestyles, putting into practice concepts like what it means to be a smart citizen and how this intertwines with government big data. The groundwork is already laid. When we hear "3D printing," we often imagine small items like phone cases or prosthetic limbs. But globally, research is underway to build entire houses with 3D printers. I visited Barcelona for an inspection, and they've launched smart city projects integrated into urban planning. Each citizen shares information via smartphones, and they aim to build entire lifestyles from that big data. The sheer scale was inspiring. Digital fabrication feels as commonplace as air there, like they're two phases ahead of Japan. European Fab Labs are now focusing heavily on the bio field. They're delving into physical nervous systems, measuring brain data, and even creating edible houses where mushrooms grow, or bacteria (algae) that generate electricity at a size comparable to a tatami mat. Despite high unemployment and living costs, there's a culture of tackling these challenges positively. The government recognizes that relying solely on public resources is inefficient, so projects involving private companies are expanding. Moreover, they embrace releasing things to the public even when incomplete, allowing for improvement through test marketing. If Japan could shift away from companies bearing full responsibility, it might gain more freedom.

──Conversely, I think that meticulousness has been one of Japan's strengths until now. But perhaps it doesn't necessarily fit the society of the future.

Watanabe: I think it's a mixed bag. Products that are already well-established don't need to be disrupted. But when corporate employees consider creating something new, waiting three years for commercialization is too slow. It would be good if we gradually embraced that sense of urgency and the idea of developing while building.

──I've also heard that companies introducing 3D printers into their development departments see ideas flowing freely, accelerating the pace of innovation.

Watanabe: I think that's true. Presentations aren't just PowerPoints or videos anymore; you can actually build and show prototypes. Plus, you can spot failing projects earlier. Some people are really good at writing proposals, but when you see the actual thing, it just feels off (laughs). Recognizing that reduces wasted costs and fosters a healthier environment where genuinely good ideas survive. That might actually have a bigger impact.

──Digital fabrication has this worldview where information circulates globally while physical goods circulate locally. How do you see the relationship between global and local in the internet age?

Watanabe: In my view, local is where people train to use digital fabrication tools and "grow." Meanwhile, making things connects globally; people move, gather in different places, and make new discoveries. I imagine it as facilities serving as communication infrastructure, linked by global connections, with both data and people moving. People feel uneasy without a home base to return to, so having more rootless, floating individuals doesn't lead to happiness. When nurturing something, I believe you need both "people of the soil" who put down roots and protect it, and "people of the wind" who bring in new things. Global and local aren't separate; they mutually invigorate each other. I feel the Fab Lab comes alive just when members from Kamakura return after participating in workshops in places like Taiwan or elsewhere in Asia. And those "people of the wind" and "people of the soil" don't have to be the same people forever; it's okay for them to change. Like, this month, I'll be the wind, haha.

──You pointed out that what we see in digital fabrication isn't "collective intelligence" but "derivative intelligence." Does that kind of thing happen often?

Watanabe: There's a leather slipper project by the unit "Kuruska," formed by leather artisan Naoki Fujimoto and design director Aya Fujimoto, after they learned to use the laser cutter at Fab Lab Kamakura. Originally, it was a project for people with disabilities: parts were pre-cut with the laser cutter, and they handled the final gluing and sewing. But one day, a Fab Lab nomad traveling the world contacted them wanting to make these slippers. Since cowhide is expensive, he made them using the leather of a local white-fleshed fish called Nile perch, right where he was in Kenya at the time. They turned out incredibly cool. They were even gifted to the grandmother of former U.S. President Obama, who lives nearby.

In this way, ideas as "derivative knowledge" are added to the open data, adapted to local environments and contexts. Right now, I'm working with an artist to create a robot. He says it's incredibly interesting to see something like an evolutionary theory of derivative forms emerge after I create the first one.

──In terms of freely expressing your thoughts and seeing them connect, digital fabrication shares similarities with social media. How do you view social media?

Watanabe: As creation methods diversify, so do sales methods. Buyers look at details and stories—who made it, their intentions, the process, materials—so it's ideal to share the process on social media while leaving room for personal touches, creating something collaboratively. Even for company projects, "who is behind it" becomes crucial. Advertising approaches will likely change too.

Also, it pairs well with making gifts for birthdays or anniversaries. People then post those creations on social media.

Creating future lifestyles and ways of working tailored to each individual

──Do you have a vision for the future of digital fabrication?

Watanabe: I hope we can create a society where everyone can choose their own balance of lifestyle and work at various stages. The current social system is like forcing your body into ready-made clothes and shoes—it causes wear and tear, blisters, and significant mental strain. If each person could tune themselves to society, it would be positive. Seeing the changes in people who come here, the act of creating is full of positive power. I believe it's not about adapting oneself to new things in the future, but that each individual exists, and there is a future tailored to them. That way, we can break free from stagnation and move a little further ahead.

Even large corporations are now fostering internal ventures. If we can envision a scenario where smaller entities tackle what larger ones couldn't, nurturing these initiatives to grow together, both sides can thrive. For workers, it would be ideal if they could choose between options offering the same pay. For instance, Singapore's education system operates on the principle that a society where everyone becomes a venture isn't necessarily happy. It identifies early on what people enjoy or have aptitude for and trains them accordingly. People who find joy in meticulously executing tasks as instructed, supporting those in ventures, are absolutely essential. Large corporations need this diversity, and many people seek it. It would be ideal to have that flexibility—the ease of moving between roles without leaving the company, that kind of acceptance. No matter how open the data becomes or how good the equipment gets, what matters is how many people can use it, and that requires training. You can't truly know what you can do until you've tried it and become familiar with it to some extent; imagination is also needed. We believe the current high school students, the digital natives, will generate new ideas, so we see ourselves as the bridge until then.

──Some experts envision a future where 3D printers themselves create other 3D printers, driving overall evolution.

Watanabe: Next year's theme is Fab Lab 2.0. The concept is that if you have one Fab Lab, you can create all the equipment needed for the next Fab Lab right there. It's about self-replication, building machines tailored to the users' needs. Eventually, specialized Fab Labs might emerge, and such derivatives could be fascinating. At Fab Lab Kamakura, when we expand for the next phase, we want to gather materials from the mountains or utilize local resources to build things ourselves. We plan to make finished products open-source, with all data available for download.

──How do you think digital fabrication will change society and people going forward?

Watanabe: I believe it's a double-edged sword. But if used properly, it becomes a truly positive and powerful tool. I want to steer it in that direction and cultivate people who can use it that way. I also want to propose a new way of learning – one that's not rigid, but fun, immersive, and where you realize you've acquired skills without even noticing. I think becoming engrossed is a talent. But the trigger for that varies from person to person, so I want to create spaces where that switch gets flipped.

I want to change people and provide opportunities for that change. But it's incredibly demanding for teachers to learn all this in schools. To support them and co-create programs, we're first organizing an international conference this year-end, co-hosted with Stanford University, to explore digital fabrication and the future of education ( http://www.fablearnasia.org/ ). I want to see what kind of people gather there and what happens.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

2015/09/20

What is Post-Internet? ──The Cutting Edge of Contemporary Art Born from Digitalization: Media Artist Akihiko Taniguchi

2015/09/03

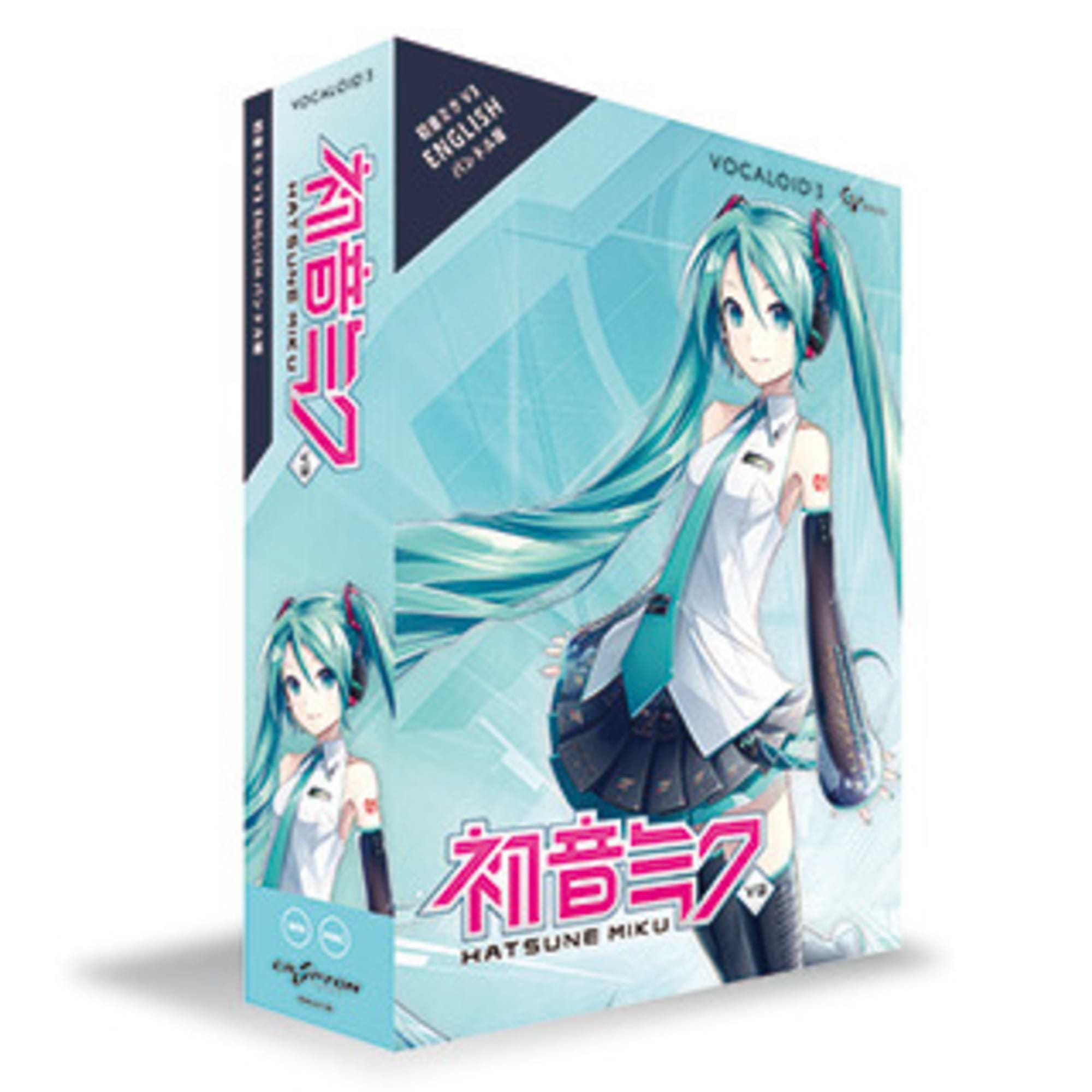

Designing the Digital Shapes the World—The Creator of Hatsune Miku Speaks on the "Future" ~ Mr. Wataru Sasaki, Crypton Future Media

Author

Watanabe Yuka

Fab Lab Kamakura

Fab Lab Kamakura Representative / Representative Director, International STEM Learning Association (General Incorporated Association) Born in 1978. Graduated from Tama Art University, Faculty of Art and Design. After working at an urban planning office and a design firm, co-founded Fab Lab Kamakura in 2011 with Associate Professor Hiroya Tanaka of Keio University, establishing East Asia's first Fab Lab. Engaged in activities to build 21st-century creative learning environments that connect local communities with the world through the proliferation of digital fabrication tools. Co-authored books include Practical Fab Project Notes and What is Possible with FAB.