DENTSU Ecosystem LAB addresses various challenges in ecosystem conservation and considers communication strategies for solving them.

This time, LAB members interviewed Associate Professor Shigeki Morimura of Kyoto University's Wildlife Research Center and Ms. Seiko Fukushima of the Ministry of the Environment about how to consider the global decarbonization efforts from an ecosystem conservation perspective. From their insights, we explore the benefits for companies in considering ecosystem conservation and how to approach decarbonization measures.

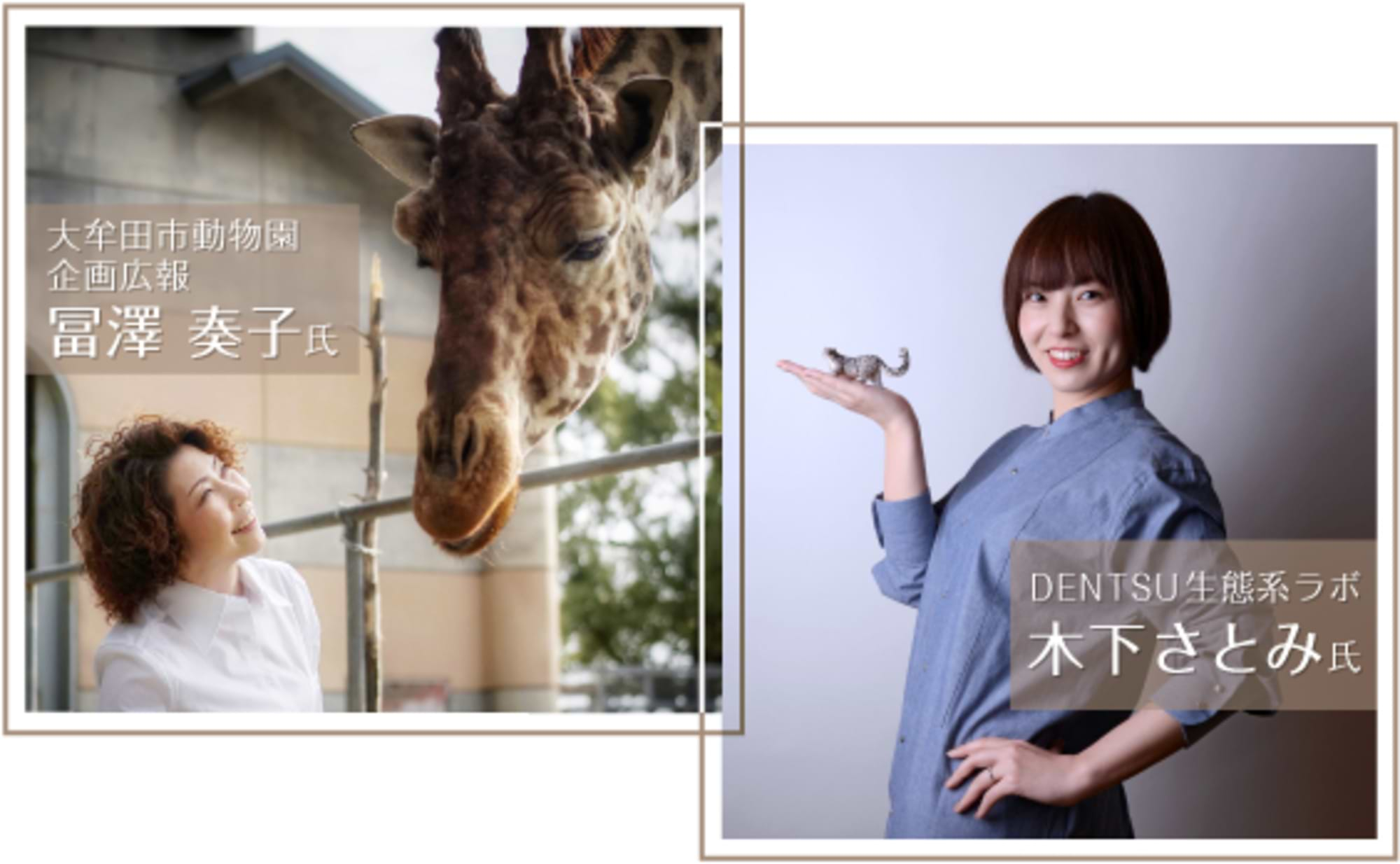

【DENTSU Ecosystem LAB】

A planning and creative unit that collaborates with researchers of wildlife, forests, rivers, and oceans, endangered species conservation groups, zoos, and aquariums to create communications centered on environmental challenges, ecosystem conservation, and the SDGs.

"Decarbonization," with its clearly defined goals, versus "ecosystem conservation," requiring a long-term perspective

—First, please tell us about the work and research you are currently involved in.

Fukushima: I currently work at the Kinki Regional Environment Office of the Ministry of the Environment, promoting community development based on the concept of "Regional Circular Symbiotic Areas." This initiative aims to shift from our current urban-centric society toward a self-reliant, decentralized society. By effectively utilizing and circulating local resources within each region, we seek to solve regional challenges and foster economic circulation. To make it easier to visualize, we also refer to it as "Local SDGs."

Morimura: My research focuses on chimpanzees. I conduct fieldwork with wild populations living in Bossou Village and the forests of Mount Nimba in Guinea, West Africa, alongside psychological studies using captive populations in zoos and similar settings. When advancing ecosystem conservation and climate change countermeasures, I believe it's crucial not to consider only human comfort, but to ensure all living creatures can enjoy behavioral freedom.

―From the perspective of ecosystem conservation in your current work and research, have you observed any impacts or changes stemming from the global push for "decarbonization"?

Morimura: In Guinea, fire is a crucial tool, and traditional slash-and-burn agriculture is common. However, the scale is so large that it causes wildfires, such as those that burned the entire Nimba Mountain range, leading to the long-term loss of forests where chimpanzees live. Continuing this practice simply because it's "traditional agriculture" has devastating consequences.

Scenes of slash-and-burn farming in Bossou Village. A chimpanzee is pictured within the photo. See if you can spot it.

If Guinean farmers could continue farming without using fire, forests wouldn't be lost on the current scale. I feel the global spread of the "decarbonization" concept is helping to drive this shift in methods.

Fukushima: Decarbonization is also a major pillar within the "Regional Circular Symbiotic Sphere" concept. Transforming the relationship where rural farming, mountain, and fishing villages are developed solely as power sources for cities, leading to one-sided resource extraction, is also a direction the Regional Circular Symbiotic Sphere aims for.

Furthermore, considering the global environment that sustains human life, both decarbonization and ecosystem conservation are said to require critical efforts by 2030. Both are essential conditions for a sustainable society and must be pursued in parallel. However, decarbonization, for which Prime Minister Suga has set clear targets, is now accelerating rapidly.

Decarbonization efforts focus on identifying where carbon dioxide is emitted and how to reduce it, making the necessary actions relatively clear and easier to quantify. Ecosystem conservation, on the other hand, requires examining the interconnectedness of all elements—living organisms, their surrounding environments, and human activities—making it highly complex. It's difficult to determine what needs to be done and to what extent. I feel a sense of urgency, concerned that decarbonization might be prioritized over ecosystem conservation before we can adequately address the latter.

Morimura: Of course, what Mr. Fukushima said is true, but furthermore, I feel there's a widespread misunderstanding that "ecosystem conservation" is included within "climate change countermeasures." That is, there seems to be an image that "climate change countermeasures" refer to things like forest protection, and that "ecosystem conservation" is done as part of that forest protection.

But that's not actually the case. For example, no matter how much we protect a forest, if the wildlife living there becomes extinct due to poaching, the animals in that region won't recover. While "climate change countermeasures"—which include forest conservation and decarbonization—and "ecosystem conservation" are closely related fields, they are by no means the same thing.

Current "climate change countermeasures" focus on how to protect forests, mountains, and rivers, and how humans can live within them. But wouldn't it be valuable to shift the perspective of "how humans live" to "how we coexist with the animals already there"?

Focusing solely on "decarbonization" risks disrupting the ecological balance.

―As decarbonization efforts accelerate, what concerns do you have regarding impacts on ecosystems?

Fukushima: For instance, to promote renewable energy for decarbonization, the Ministry of the Environment and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry are currently relaxing environmental impact assessment (EIA) regulations for wind farms. EIA is a mechanism—essentially a form of regulation—used for large-scale development projects to investigate, predict, and evaluate environmental impacts beforehand, aiming to refine project plans from an environmental conservation perspective.

Relaxing these regulations could encourage companies to build more wind farms. While this might advance decarbonization, it also risks development proceeding without sufficient prediction or evaluation of impacts like increased bird strikes from wind turbines crowding flight paths, or habitat loss for animals due to clearing mountain ridges.

Beyond environmental assessments, as deregulation discussions take precedence, mechanisms to ensure ecosystem conservation are not being sufficiently considered. While advancing decarbonization is critically important, making it an end in itself risks creating such imbalances.

Morimura: Indeed. Ensuring that the balance, including ecosystems, is not disrupted will likely become a new role for us researchers going forward.

Ecosystem conservation isn't just about protection; it's crucial to consider how to effectively match it with development.

―Considering the decarbonization trend, what significance do you see in companies thinking about ecosystem conservation? Also, if there are things they can start doing now, please tell us.

Morimura: For example, when aiming to protect a chimpanzee forest, we must also consider alternative livelihoods for the local residents. To advance nature and ecosystem conservation, we need a perspective focused on how to effectively pursue development that allows local people to live without destroying nature. Conservation isn't just about protecting; it's about finding the right balance with development. This is where collaboration with companies becomes highly meaningful.

Fukushima: Among corporate initiatives, decarbonization is gaining momentum, but progress in ecosystem conservation remains slow. A long-term perspective is indeed essential. I believe unexpected business opportunities lie in delving deeply into why both decarbonization and ecosystem conservation matter, rather than being confined by the mindset of "our company does this because..." Grasping the essence of these issues should also enhance corporate value.

In that regard, focusing on carbon offsets is also important. The Ministry of the Environment has compiled guidelines titled "The Approach to Carbon Offsets in Japan." Carbon offsets are a mechanism where, while making efforts to reduce carbon dioxide emissions, the portion that cannot be reduced is compensated for by purchasing credits representing CO2 reductions or absorptions achieved by other companies or organizations.

While making decarbonization the "goal" itself is dangerous, at this stage where achieving the ultimate goal of a 100% renewable energy cycle is difficult, I believe it remains an important system. Whether a company takes even minimal action using methods like carbon offsets, or does nothing at all, will likely create a significant difference in corporate value down the line.

<From DENTSU Ecosystem Lab, after the discussion>

"We built a human-centered world, only to create an Earth where humans can no longer live comfortably." I felt this statement by Mr. Morimura during our discussion encapsulated everything.

Looking around, society appears to function on the flow of people, yet all economic activity is intrinsically linked to the Earth's environment and ecosystems. While companies advance toward concrete targets like CO2 emission reduction goals, we must not forget the importance of maintaining a long-term, broad perspective – one that transcends immediate challenges and numbers.

On the other hand, this "decarbonization" trend can also be seen as an opportunity for companies to "enhance their own value through business." Fundamentally, corporate decarbonization (including measures to avoid penalties) is becoming the norm, and the next phase of action has already begun.

Overseas, even in carbon offsetting, initiatives that contribute broadly to the entire SDGs—such as ecosystem conservation and supporting local economic activities—are gaining greater value. A structure is emerging where approaching decarbonization as a business, rather than mere "social contribution," directly benefits the company's own interests.

In other words, the "society" in decarbonized society encompasses not just the environment, but the entire ecosystem's mechanisms, the lives of its inhabitants, and the whole economic system. Companies that can develop initiatives incorporating this broader societal perspective—beyond mere energy-saving or renewable energy business development—may be the ones expanding globally in the future.

Furthermore, I sensed that considering "ecosystem sustainability" might actually offer significant insights for our daily lives. "Pursuing only our own short-term profits may conversely shorten our own lifespan." "Depriving ecosystems of diversity diminishes their very capacity for survival." Applying this to one's own company, organization, or business could yield diverse perspectives for achieving sustainable evolution.