Today, many companies continue to invest significant time and effort into formulating their "Mission, Vision, Values" (commonly referred to as "MVV").

The stated purpose—"to codify the mission, philosophy, and guiding principles that form the foundation of corporate management, fostering shared understanding from top management to the front lines to enable unwavering decision-making"—sounds perfectly reasonable. The same goes for the "purpose" trend popular in recent years. The explanation—"clarifying an organization's reason for being (beyond just making money) to build a fanbase that transcends competition with rivals"—is appealing.

But what about reality?

I've witnessed countless cases where MVVs and purposes, painstakingly formulated through endless meetings involving everyone from the president down to the front lines, sadly end up as pie in the sky. Even when communication investments are ramped up to embed them, the situation often remains unchanged, and before you know it, they settle into being mere words decorating a corner of the company profile.

To be a bit more candid, I've even heard members involved in creating purposes like "Delicious food for smiling tables" or "Miso, reimagined" express their own doubts: "Was this really okay?"

A lingering unease remains: "I understand we shouldn't voice dissent since it's a shared value, but there were more compelling discussions during the meetings..." or "Maybe trying to unify the organization around a purpose is inherently flawed..."

The goal itself was sound, so where did we go wrong?

The root of this problem likely lies in the very attitude of trying to "correctly" set the "purpose" or "MVV." You might be thinking "Huh?" at this sudden statement, but actually, modern businesspeople are unconsciously bound by the organizational view that "an organization is an information processing device; if you give the right instructions, it will function correctly (so 'correct instructions' are necessary)." When the front lines are also constrained by this view, management that doesn't give "correct instructions" appears negligent. This leads to the belief that "if there's anything requiring judgment, we need a purpose as the definitive 'incarnation of correct answers' (a sacred text) to serve as the standard."

In contrast, there's a perspective that views the organization as a "knowledge-creating ecosystem." This sees each member as a creative agent—not merely someone who executes correct instructions. From this organizational viewpoint, what drives the organization isn't "correct instructions" but "dialogue." Above all, we fear that the workplace will become "stagnant" due to the existence of "scriptures" that are so unquestionably correct. In other words, it is important that management-side terms such as purpose and MVV become "good questions" that encourage "dialogue."

When considering what constitutes a "good question," a useful hint can be found in the concept of "realistic idealism" advocated by Jim Collins, author of the classic book Built to Last: Successful Habits of Visionary Companies. Unlike "flawless (correct) ideals" such as "delicious food and smiles at the dinner table," this is a "hypothesis" that sometimes provokes controversy but has a "flexibility" that motivates the frontline to take action, and that is why it induces "dialogue" with management.

And here's the important part: a "good question" is not something that needs to be asked only once at the beginning. It is something that should be asked repeatedly, over and over again, as long as the organization continues its activities. And it is not necessary for there to be only one question per organization. As society's values change, management should ask countless questions about each and every organizational activity, such as, "Is this the right thing to do here and now?"

Because it's a "dialogue," management's own ideals may evolve through the process of experiencing the realities on the ground. And through repeating these countless interactions (dialogues), the organization may eventually arrive at a single, overarching "purpose."

Articulating and sharing this is wonderful, but even the "purpose" born this way must not be fixed as a sacred scripture of truth. Instead, it must be used as a "question" that challenges the creativity of each and every member of the organization.

Simon Sinek's approach of starting with "Why" is a highly effective "communication tool," but it is distinct from "how to create products and services that move customers emotionally."

*Simon Sinek =

An American consultant. He proposed the "Golden Circle Theory," which suggests that effective leaders communicate their vision in the order of "Why ⇒ How ⇒ What" to inspire action and foster empathy.

As previously discussed in this column, it is the "Golden Spiral" of top management's "power to question," frontline staff's "power to create," and middle management's "power to choose" that serves as the driving force propelling an organization toward autonomy.

Now then.

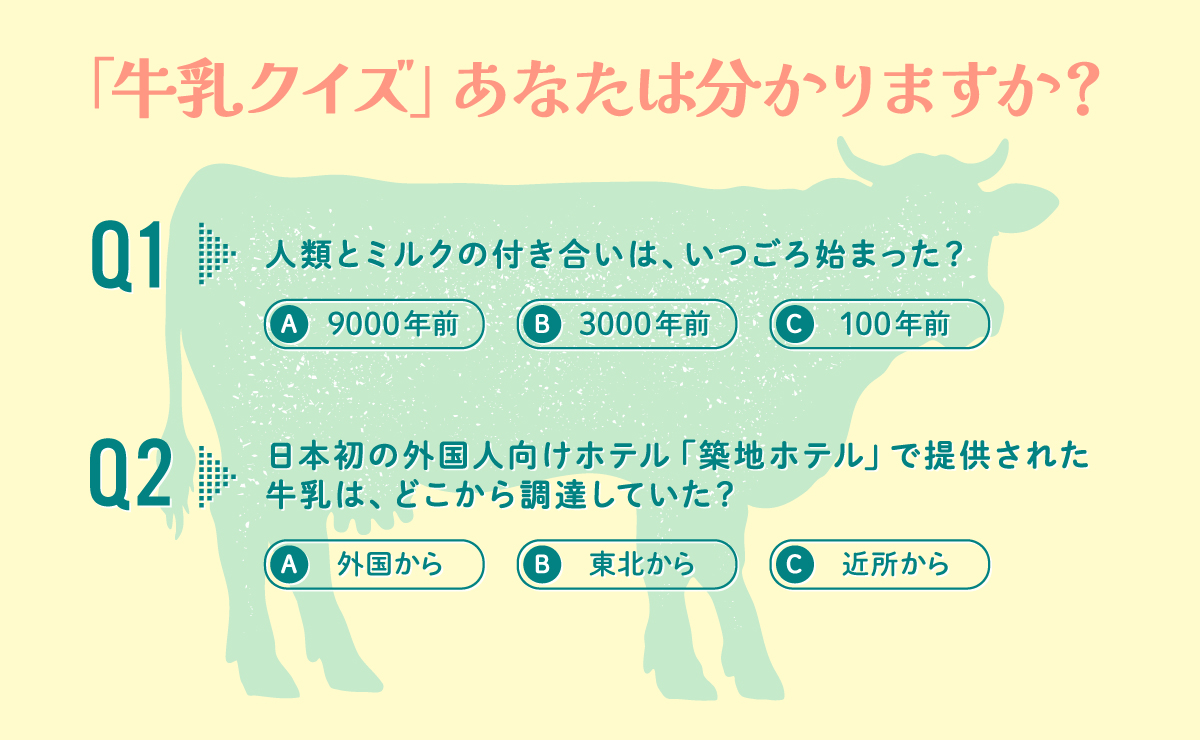

If asked, "Why do I keep going back to my wife's hometown of Takamatsu?" I'd say, "For the endless loop of udon → tennis → Setouchi whitefish and local sake – I just want to relax."

But the other day. A friend took me to this hidden gem of a Moroccan restaurant tucked away in the city center, and it was absolutely amazing.

From the diverse mezze to the couscous, the famous mutton tagine, and more, I thoroughly enjoyed an encounter I never expected. Definitely going back. It really seems like challenging yourself and new experiences are important in everything.

Enjoy!