(※Affiliation at time of publication in "Ad Studies")

As marketing and consumer behavior research advances, concerns grow about the disconnect from practical application. What, then, is truly expected of academia?

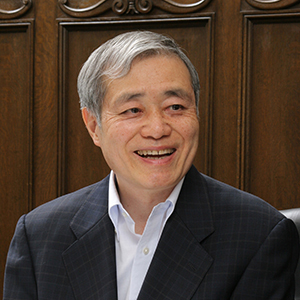

We welcomed Professor Shuzo Abe of Waseda University, a distinguished visiting professor who has focused on analyzing consumer behavior and building highly accurate, predictable theories within academia, as our guest. Together with Professor Satoshi Hikita, formerly of Toyo University, who has engaged in theory research applicable to reality based on his practical experience as a businessperson, they discussed the intersection between academia and practice, as well as new forms of collaboration.

Inside and Outside Academia

Hikita: First, Professor Abe, could you tell us about your journey within the world of academia?

Abe: At Meiji University, I studied under Professor Takeharu Tone. At Hitotsubashi University's graduate school, I studied under Professor Koichi Tanai. After that, I served as a full-time lecturer and associate professor at Nihon University's Faculty of Economics for five years. Then, at the invitation of Professor Ryusuke Kubomura, I spent about 30 years at Yokohama National University. Since turning 64, I have been working as a special professor at Waseda University.

Regarding connections to my own research, I spent a year studying under Professor James R. Bettman, a leading expert in consumer information processing, at the University of California, Los Angeles. After that, I studied for about half a year under Professor Richard P. Bagozzi, a leading expert in covariance structure analysis, at the University of Michigan. I believe this experience in the United States had a significant influence on my research style.

Hikita: I joined Professor Murata's seminar at Keio University. After entering graduate school, I became interested in advertising and business, while also studying a little philosophy of science. Upon completing my doctorate, I consulted with Professor Murata and decided to join the Nikkei newspaper. I maintained connections with academic circles afterward, but being away made me miss the university environment. By chance, I found a position at Toyo University. My life philosophy is that it's better to try various things (laughs).

By the way, people often ask whether academic studies or theories are useful in practice, or claim that theory and reality are different. However, based on my own experience, I don't take the position that practice and theory are different. The media, critics, and so-called intellectuals who say theory and reality are different seem to know very little about reality and haven't studied theory thoroughly either.

Abe: I believe practical work becomes superior when grounded in theory. Consider the lunar rocket, for example. Precise orbital calculations and mission success were only possible because we applied Newtonian physics, like the law of gravity. The notion that theory and reality are polar opposites fundamentally misunderstands theory, doesn't it?

I was purebred in the academic world of universities, but for the first ten years, I kept a close eye on practical work too. I worked with industry professionals at the Japan Productivity Center to build simulation models of consumer behavior, and I was involved in decision-making for private companies. We predicted how many customers a large shopping center could attract and were able to forecast annual sales with considerable accuracy. That was because theory proved useful.

However, since we haven't yet sufficiently developed theories or models capable of high-precision forecasting, I think there's an element of inevitability to many practitioners saying theory is useless.

Explanation, Prediction, and Control

Hikita: Is there a difference in what practitioners and academics mean when they talk about "theory"?

Abe: They might. Researchers in marketing and consumer behavior strive to create theories that explain the real world, so they don't consider detaching from reality. Practitioners, however, might think theory is too difficult and not practical for real-world use.

Hikita: I looked up the general definitions of "academic discipline" and "research" in the Kōjien dictionary. It states that "academic discipline" means "the pursuit of learning," while "research" means "thoroughly investigating and contemplating to uncover truth." In your recent book, Consumer Behavior Research and Methods, you use the phrase "academic disciplines born of necessity." What kind of necessity was there? Who felt this necessity? Or, are there academic disciplines that emerge even when there is no apparent necessity? What are your thoughts on this?

Abe: I don't think it matters how theories are born or how they are used. For example, when studying the movements of distant stars out of intellectual curiosity, it doesn't immediately serve a practical purpose. However, certain fields of study do arise from necessity, not just curiosity. They emerge from needs like wanting to cure diseases, eliminate waste, or—in marketing terms—avoid risks. As for who drives this need, it could be companies, consumers themselves, government agencies, or consumer groups—any of these entities is fine.

However, while my book clearly positions consumer behavior theory as a specific topic within marketing theory, I don't insist this is the only way. I believe it's fine to research it from any perspective. When we say it's a specific topic within marketing theory, what significance does that hold? There are three major purposes:

The first is an explanatory purpose: to understand why consumers choose a particular product. The second is a predictive purpose: to forecast future behavior. The third is a control purpose: to steer behavior in a desired direction. Consumer behavior researchers tend to show less interest in this third control aspect, as it often becomes a matter of marketing or practical implementation.

Consumer behavior researchers focus on explanation and prediction. This is where the philosophy of science comes into play; I believe the philosophical stance naturally follows depending on whether explanation or prediction is prioritized. Many people, including practitioners and researchers, seem more interested in prediction than explanation. Companies, too, often prefer systematically and economically grasping the phenomena before them over using knowledge or theory to explain them.

Hikita: That aspect certainly exists.

Abe: Those who emphasize explanation and downplay prediction tend to think that how their theories are used in practice is irrelevant. Their goal is to bring explanation closer to deeper truth. This approach, which places weight solely on explanation, aligns with the falsificationist position in the philosophy of science. Prediction is seen more as the technician's job. Prediction is induction. It's based on the observation that certain things have occurred under certain conditions in the past, so we expect the same to happen tomorrow. However, induction has logical problems.

For example, if we observe 100,000 crows and conclude "all crows are black" because they all appear black, discovering a single non-black crow invalidates that proposition. Falsificationism argues we should build knowledge systems free of such induction, demanding induction be excluded from science. However, I acknowledge that since we haven't yet developed explanatory theories or models that reliably aid prediction, this approach is vulnerable to criticism. Nevertheless, I believe the work of researchers and scholars is to pursue both explanation and prediction.

The Limits of Instrumentalism

Hikita: By the way, if we pursue how much explanation is possible to its extreme, it becomes increasingly abstract and may end up merely chasing an ideal. To put it somewhat bluntly, while seeking the bluebird may indeed be noble, it might be acceptable for an ordinary citizen. But for someone in the position of an academic, who at least bears a certain responsibility entrusted by society, there is also the question of whether that is permissible.

Abe: I think it's problematic to pursue only ideals while ignoring practical realities. Science strives to enhance explanatory power toward that ideal. My position is scientific realism, which seeks both explanation and prediction. It's the idea that science is an approach to truth. While theories certainly possess fallibility and the potential for error, I believe they will inevitably prove useful in reality over the long term.

Consider current consumer behavior theories or models: at best, they explain only about ten to fifteen percent of the statistical variation in phenomena. Does that mean we should discard them as useless because the remaining eighty-odd percent remains unexplained? I don't think so. What matters is making various improvements and striving to expand the areas we can explain.

For instance, practitioners gain a competitive edge by possessing knowledge that puts them ten or so percentage points ahead of their rivals. Similarly, by coherently combining several effective theories—each contributing 10%, 5%, and so on—we can create a significant gap, even if it doesn't deliver a decisive blow. Researchers bear the responsibility to elevate this level and make it as usable as possible.

Hikita: We often discuss separating theory and practice. Does this mean we fundamentally understand that practice must be guided by theoretical principles?

Abe: Since the goal is to produce something useful through praxis, this doesn't mean instrumentalism—the view that theory is merely a tool for prediction—is useless. Instrumentalism has produced quite excellent research results. However, if we accept that something is acceptable simply because it works, even if it contradicts fundamental premises, we risk settling for something fundamentally different from what we truly aimed for.

To take an extreme example, the lunar calendar stems from the idea that the moon and sun revolve around the Earth. Following this, it allows predictions like when the spring tide will occur or when it will get cold, making it quite useful for agriculture and fishing. However, if we simply say it's fine because it works, that could lead to the conclusion that knowledge of the Earth revolving around the sun is unnecessary.

However, when we have a consistent explanation and prediction system—that the Earth and Moon orbit the Sun—it leads to higher precision and practical utility. Science strives to explain the real world and phenomena with increasing accuracy. Just because an explanation works once doesn't mean it's the ultimate truth. Science aims for better explanations. It's fine for practitioners to adopt instrumentalism, but it's not desirable for researchers and academia to become steeped in an instrumentalist atmosphere.

〔 To be continued in Part 2 (Final) 〕

※The full text is available on the Yoshida Hideo Memorial Foundation website.