We spoke with Hiroaki Iima, who, while engaged in the work of dictionaries, constantly observes how the meaning and usage of Japanese words change in response to shifts in society.

Why dictionaries?

The catalyst for aspiring to compile Japanese dictionaries was encountering a book titled "The Trash Bin of Words" by dictionary compiler Hideto Kenbo. This book lists "unused words" collected by Mr. Kenbo during dictionary compilation but ultimately not included. It featured fascinating words, like how department store clerks use the slang term "shinegari" (literally "item reduction") to refer to shoplifting. Learning that dictionary compilers exist who collect such rejected terms, along with an absurdly vast number of modern words, made me want to create a Japanese dictionary myself.

But when I went to bookstores, the spines of Japanese dictionaries bore names like Kyozo Kindaichi or Izuru Niimura. It seemed you couldn't compile a dictionary unless you had some kind of cultural honor. I thought, "This is impossible for me."

Then, while in graduate school at Waseda, I had a professor involved with Sanseido's Thesaurus. I got the chance to contribute by writing drafts. Influenced by Mr. Kenbo, I'd started collecting modern words myself and showed them to the Sanseido people. After that, they invited me to "become an editorial committee member." I became one without having a Cultural Medal.

When I could observe something myself and write an explanation that captured its essence—something that truly described the subject—it gave me immense pleasure. I became addicted to the work of "observing and explaining words."

"Love" is fleeting

Japanese dictionaries have their own personalities. Look up "love" in the Kōjien dictionary, and the very first definition states: "A strong, yearning attraction to someone you cannot live with or who has passed away." So if you say, "I'm in love," someone might ask, "Has someone died?" And in the era of the Manyoshu anthology, that was actually the case. The meaning of romantic love comes later in the definition. The Kōjien is a dictionary that broadly surveys meanings from ancient times to the present.

In the previous edition (6th edition) of our Sanseido Japanese Dictionary, "love" was defined as "an unfulfilled feeling between a man and a woman, involving liking someone, wanting to meet them, and desiring to be with them forever." You might think love can sometimes be fulfilled, but the core meaning of expressions like "to pine for" (恋い焦がれる) centers on feelings for someone not present. To say you yearn for your wife who lives with you is a bit odd in Japanese usage. Love requires that the other person is distant or doesn't return your feelings, creating an unfulfilled longing.

When love is fulfilled, it takes on a different name. It becomes the emotion of cherishing the other person – "love."

Actually, in the latest 7th edition, we've subtly changed the explanation for terms like "恋." Previously, the old edition stated "between men and women, liking someone, wanting to meet them." We've now changed it to "liking a person, wanting to meet them," shifting the focus to "person." This is because LGBT (sexual minority) rights have come into sharper focus, and "between men and women" is now considered discriminatory against minorities.

Criticism often targets "language evolution." Yet change is the very essence of language. It's as inseparable a quality as a fish swimming or a flower blooming.

Words are meant to stretch and contract like rubber, adapting to rapidly changing situations. Think of changing them as the normal way to use language. Differences in meaning across generations and societies arise because they are necessary.

Advertising and Language

Ad copy intentionally shifts the usual meaning of words just a little. Observing this, I sometimes find the resulting shift in meaning uniquely interesting.

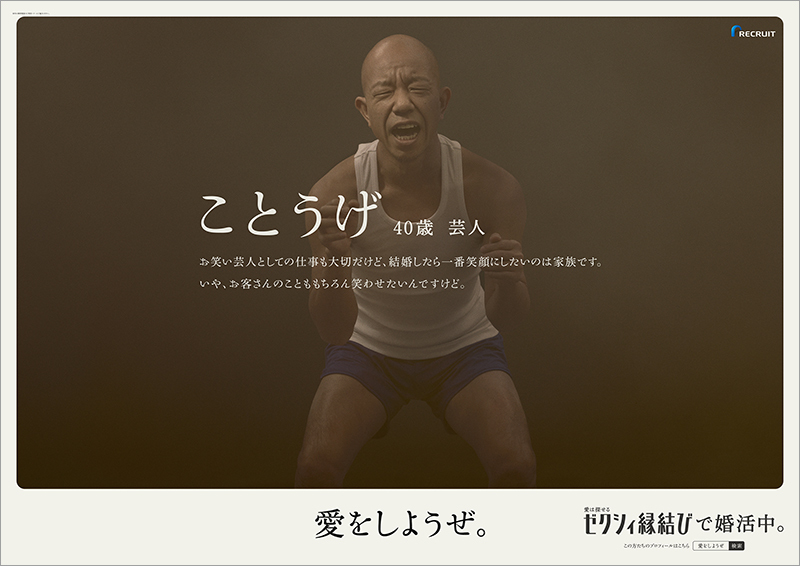

The station ad for "Zexy Enmusubi" that says, "Let's make love." I saw it at Shibuya Station just as I was pondering "romance" and "love." I stared at it intently, thinking that while you can "fall in love," you probably can't "make love."

The Sanseido Japanese Dictionary defines "love" in multiple entries. The first is "a feeling of cherishing and wanting to protect someone or something." The second is "a feeling of cherishing someone you're romantically attracted to." Referring to these definitions, a clear message emerges from the "Let's make love." copy.

Most of the unmarried men targeted by the ad have already experienced plenty of "romance"—that longing for someone. So the message is: "Gentlemen, say goodbye to your single life of romance. How about considering loving a spouse from now on?" By shifting the usage of the word, it cleverly conveys what it wants to say.

A shift in word meaning or usage isn't considered a change in Japanese just because it appeared in one advertisement. However, if people find the word interesting and start imitating it, and if enough people do so, that meaning or usage might eventually make it into dictionaries. That's when criticism like "language is becoming corrupted" tends to surface.

But note that this change happens with the support of many people. New words, meanings, or usages don't become established without reason. They take root precisely because many people think, "This is useful for new situations."

It's like when a comedian who wasn't very popular suddenly becomes wildly famous, and everyone starts imitating them. The same thing happens with words. Let's celebrate a word's rise to prominence.