Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

Three Things I Realized During My 12-Year "Proposal Writing Career"

Yuichiro Kojima

This series features Dentsu Inc. employees who served as instructors for the 2018 internship, introducing their own thinking methods, planning techniques, and approaches to work. In this final installment, Yuichiro Kojima from Dentsu Business Design Square shares key points for communicating ideas in a proposal document.

Utilize techniques across three phases to reveal the essence of your idea

"We don't need proposals," "Spending time on PowerPoint is foolish"

I often hear such statements. Yet, I've continued writing proposals for 12 years. It wasn't just for presentation materials. When I was younger, whether organizing a drinking party or mentoring juniors, proposals were my primary means of communication.

To gain trust in my ideas and make them happen, I needed to create proposals that everyone could agree on.

However, the "proposal skills" I honed then have proven invaluable in countless situations. When I wanted to write a book, having a proposal was what got me to publication. When a multi-million yen business investment was approved internally, it wouldn't have happened if I hadn't been able to translate the business concept into a proposal.

Based on these experiences, in the student internships I oversee, I emphasize it as "A day to learn skills that will be useful even if you don't end up joining an ad agency." I share insights gained from my 12-year "proposal-writing journey." Let me introduce three of them here.

I teach students not "how to generate ideas," but "how to present ideas." Saying that might invite criticism like, "What good is teaching superficial techniques?" or "You should teach more fundamental things." However, what I teach isn't merely presentation techniques. It's techniques for distilling the essence of an idea.

When translating ideas into proposals, there are three major phases:

1.Create a story

2.Choosing words

3.Organizing with Structure

First, let's discuss the key points for "creating a story."

1.Crafting a Story That Highlights the Main Character

When you hear "proposal," you might immediately want to open PowerPoint or Keynote. However, during my internship, I prohibited this. These tools, based on the "one slide, one message" principle, make it difficult to grasp the big picture and are not well-suited for story creation.

Instead, I recommend WordPad, Notepad, or Evernote. The first step in creating a proposal is to outline the entire presentation with one line per slide, keeping in mind that you'll eventually transfer it to PowerPoint or Keynote. The materials for our internship actually start from notes like this.

After creating this overall story outline, we then develop each slide into something like the examples below, adding visual elements and other design touches.

So, how do you develop the crucial "storytelling ability"? That's where the internship provides this training.

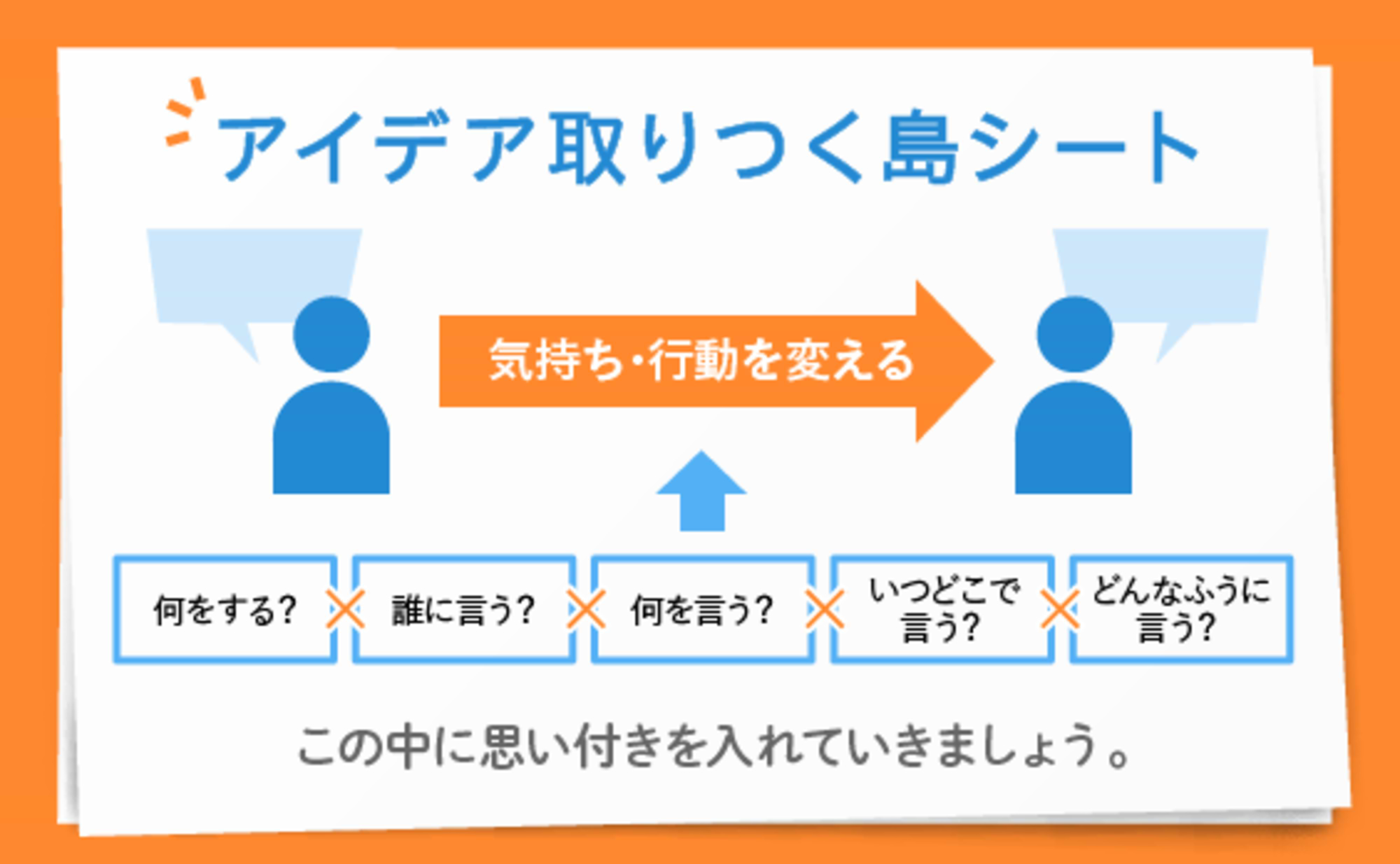

First, designate a "main character slide" in your proposal. This is the "core idea" part, as in advertising. Story creation revolves around this central character.

For example, in the diagram above, the sentence appearing in the fifth line becomes the protagonist. To make this protagonist compelling, how do we craft the story's opening? How do we develop it after its introduction? We complete the seven-line story as if we were a screenwriter.

At first glance, this might seem like training to "force a story." While it does build logical thinking skills, that's not the main goal.

The key point of this exercise is "fixing the protagonist and repeating it multiple times." Shining light on the same protagonist from various angles allows us to verify their appeal from multiple perspectives.

Ultimately, it serves to confirm whether the protagonist is truly strong enough to carry the role, while also sparking the discovery of new charms. In my daily work, I use this technique to verify whether a "core idea" is truly substantial enough to be the protagonist. A good idea is one that naturally evokes a compelling story.

2.Be mindful of the horizontal and vertical axes of language

Once the broad story framework is set, the next step is to scrutinize the words. The key here is the "horizontal axis" and "vertical axis" of language.

The horizontal axis refers to synonyms with the same meaning, while the vertical axis signifies a sequence of flow.

For example, the word "plan" can be rephrased as "scheme," or, with a slightly broader meaning, as "planning." This is the horizontal axis.

The vertical axis is the sequence of words that form a logical flow, like "planning → presentation → execution." The goal of this phase is to eliminate unnecessary rephrasing within a single presentation by being mindful of these axes.

Why eliminate unnecessary rephrasing? For instance, if within the same presentation you say "When I plan..." and then later rephrase it as "When I do planning...", the listener will switch to unnecessary thinking: "Wait, what's the difference between planning and planning?" This extra mental effort becomes "noise" that diminishes the presence of the core idea (the main focus).

I frequently encounter presentations and proposals ruined by this "noise." This is especially common among those with extensive vocabulary or knowledge.

When the perspective of "organizing the listener's thoughts" is missing, and the presentation or proposal becomes self-centered and full of noise, the result is often, "What exactly was that person trying to say?"

The function of this technique is to narrow down the types of words used and minimize noise as much as possible, thereby impressing upon the audience the "core idea you truly want to convey" (the protagonist).

3.Create a level playing field for discussion through structure

While there are countless other techniques for presentations and proposals, I'd like to conclude this discussion with structure.

While I've broadly referred to them as "proposals," I actually tailor my approach based on four distinct scenarios.

First, consider whether you can explain it yourself. If you can supplement it verbally, just include keywords in the proposal. Next, consider whether it will exist in written form. If it will be on paper, there's a chance the proposal could take on a life of its own. In this case, aim for a minimum level of readability.

Looking at these four quadrants, the most challenging type is the "proposal I can't explain myself, but will be documented on paper." This is where "structure" comes into play.

"Proposals I can't explain myself, but will be documented" often involve proposals going up to management or people beyond my direct reach. These individuals are usually busy and want conclusions quickly. However, writing only the conclusion risks multiple back-and-forth exchanges if it doesn't resonate, which is inefficient.

Therefore, always include a single page in your proposal that summarizes its core purpose through structure. The key here is "comprehensiveness."

Comprehensiveness means presenting not just "Our goal is A," but "Among options A through D, we aim for A." It's crucial that A through D cover all possibilities. This is known as MECE (Mutually Exclusive and Collectively Exhaustive). The explanation using the "four quadrants" structure mentioned earlier is one example that ensures this comprehensiveness.

The structure's effectiveness lies not only in speeding up comprehension ("understand at a glance") but also in creating a "field for discussion" – as in, "in this diagram, it's here." Preparing a comprehensive field allows for flat, unbiased discussion, free from personal preferences or biases.

This field is especially crucial for creative work, where ideas are often subject to personal preferences. If a proposal is rejected, using the prepared field to ask, "Where in this field does the idea we were seeking fit?" helps identify the direction for revisions when presenting again.

That's why internships also include training in structuring. For example, the prompt might be this:

Whether using a standard four-quadrant model, a Venn diagram, or an original chart, the structure itself isn't specified. What matters is comprehensiveness. We want participants to create a framework where discussion can happen when someone asks, "What about the movie XX?"

By learning to explain phenomena in the world through structure like this, you'll also be able to objectively explain the meaning and significance of your own ideas.

The misconception that good ideas will be adopted

My insistence on "how ideas are presented" doesn't stem from dismissing ideas as "something that can be manipulated however you present it." Precisely because ideas are important, I don't want to fail in how I present them.

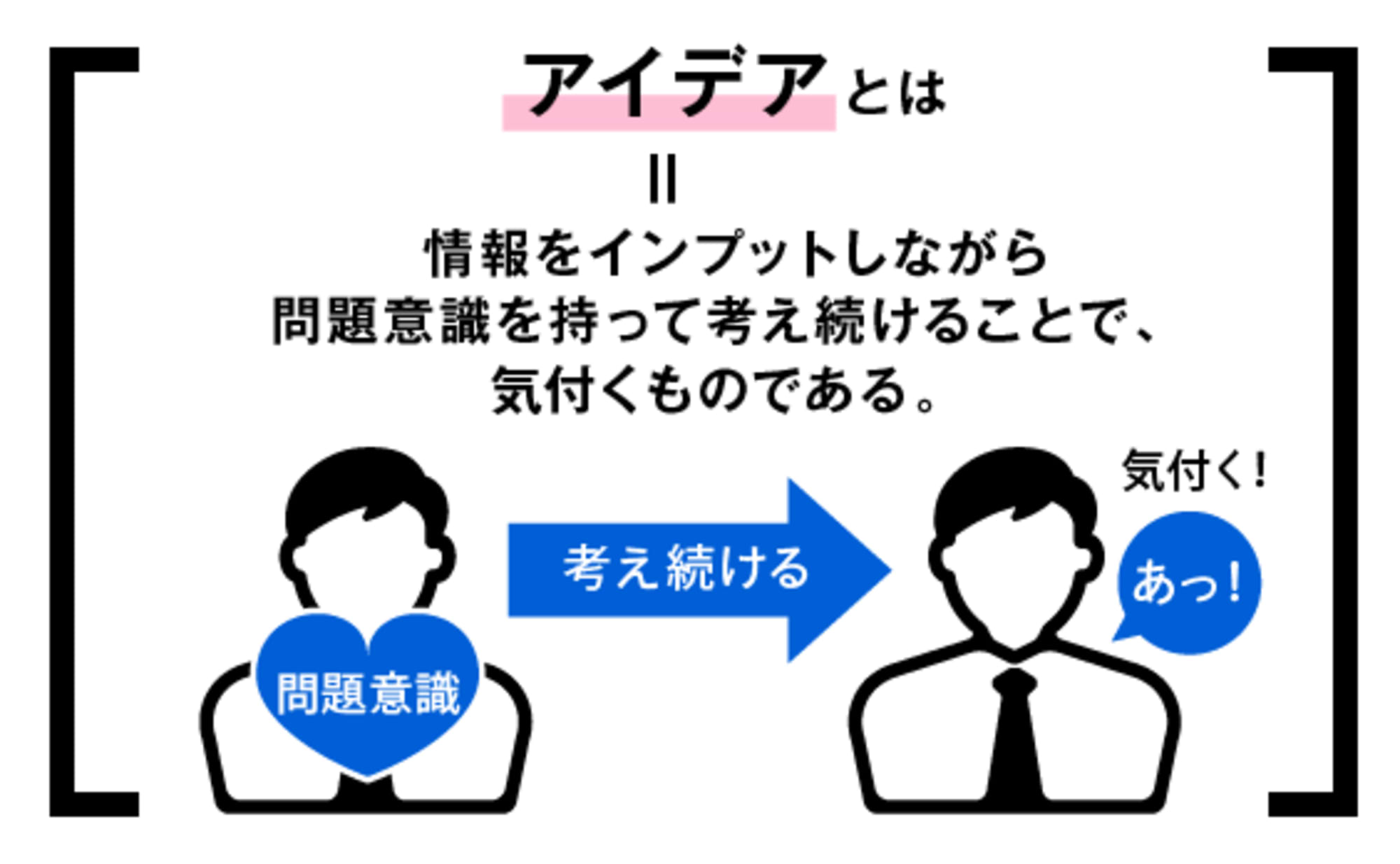

Just as "making a good product guarantees sales" is a myth, "coming up with a good idea guarantees adoption" is equally untrue. In fact, "good ideas" often exist in places beyond people's immediate understanding; their unexpected nature is precisely what makes them "good ideas."

In other words, the higher the hurdle for a "good idea" to be adopted. That's precisely why we need to properly explain the meaning and significance of that unexpectedness. I'd be delighted if the points I wrote about here contribute even a little to spreading "good ideas" in the world.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Yuichiro Kojima

While working in sales at Dentsu Inc., he won the inaugural Sales Promotion Conference Award and transitioned to a planning role. He subsequently placed in the competition for five consecutive years. While working in promotions, he launched the university club initiative "Circle Up" in 2013, which won the Good Design Award in the Business Model category. His book is titled "I Tried Job Hunting Using Advertising Methods." Other awards include the One Show in the US and the Red Dot Award in Germany. He left Dentsu Inc. at the end of November 2023.