In today's world of diverse values, it's crucial for companies to articulate their purpose within society. Amidst this, the introduction of "philosophy" into corporate philosophy formation and training is now gaining attention in Japan.

This series introduces the benefits and approach of "philosophical dialogue," which incorporates philosophy not as mere "ideology" but as a "method." The first installment covered the fundamentals of philosophical thinking and philosophical dialogue.

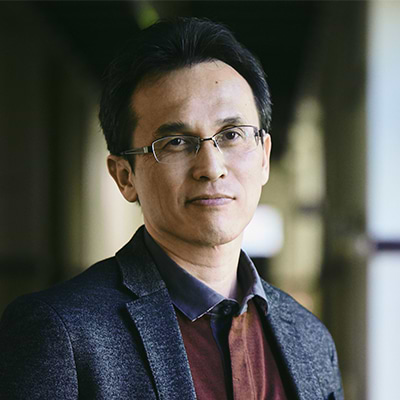

This time, Naota Nakamachi from Dentsu Inc. Corporate Transformation Department interviews Shinji Kajitani, Director of the University of Tokyo's Center for International Philosophy Education and Research for Coexistence (UTCP). We asked about the effects philosophical dialogue brings to companies and the challenges facing Japanese companies from a philosopher's perspective.

Most people have never truly experienced "proper conversation"

Nakamachi: First, Professor Kajitani, based on your experience implementing philosophy dialogue and philosophical thinking programs in corporations, could you share any differences you've observed compared to conducting them in educational settings or communities? Also, what reactions do you feel are unique to business professionals?

Kajiya: For example, when conducting philosophical dialogue in schools, students who lack motivation clearly show reluctance, and some teachers even express resistance. However, while corporate participants might initially seem confused—"What is philosophical dialogue?"—they approach it seriously as part of their work.

On the other hand, for the same reason, I sense an atmosphere where they consciously ask, "What's the point of this?" or "Will this help my work?" This stems precisely from their sense of responsibility and motivation toward their jobs. Because organizers also expect results, they often try to set dialogue themes related to "the company" or "work." For example, they might want to discuss "How can we get motivated about work?"

However, when facilitating philosophical dialogues in companies, I advise avoiding themes about work or the company. Why? Because if the theme is "how to get motivated," it stifles the very possibility of expressing the fundamental opinion: "Maybe it's okay not to be motivated."

Such themes often carry an implied "correct answer" or reflect the direction management or the company wants to steer things. Engaging in philosophical dialogue within this framework stifles free expression. In philosophical dialogue, it's crucial to first build relationships where people feel comfortable discussing even trivial topics properly, and to practice this. Only then can we begin to talk about the important, complex matters related to work.

Nakamachi: I think whether philosophical dialogue takes its proper form and works is a crucial point. In the workshops of our consulting programs, we're responsible for reaching conclusions or some form of consensus on the theme within a limited time. But philosophical dialogue doesn't rush to conclusions. In fact, I think the key point is that it's okay not to reach one. Why is it defined, as a principle, that "it's okay not to reach a conclusion"?

Kajitani: Even among adults, I believe a surprisingly large number have never truly experienced "proper conversation." Yet that experience is the most crucial. What does it mean to have a proper conversation? It's something you can't understand without actually experiencing it. Because they lack that experience, many people mistakenly believe that a good discussion is one where you efficiently lay the groundwork beforehand or persuade others to reach a conclusion smoothly.

In fact, after experiencing philosophical dialogue, we often hear feedback like, "I finally understood what it means to truly listen to someone." Other comments include, "It felt incredibly good to just say what I thought," and "I felt a sense of liberation."

This is a different kind of enjoyment from casual chatter among like-minded friends. Enjoying the act of "listening" and "speaking" itself forms the foundation for all discussions, whether in companies, schools, communities, or any setting. That's why the fundamental goal of philosophical dialogue lies precisely in this point.

Get to know 10 employees' personalities in just one hour!? By talking as people, not just in their roles, you discover new things.

Nakamachi: The reason people often struggle to "listen to others" or "communicate effectively" is likely because they're trapped within business frameworks. There's an unspoken expectation where we listen to superiors but don't place much importance on junior employees' opinions. Is the purpose of philosophical dialogue, in a sense, to break that?

Kajitani: It's not just about companies, but in organizations, many people speak within their respective "relationships." Everyone has a "role" within the situation—new employees speak as "new employees," department heads as "department heads." They aren't speaking as individuals.

This happens often in schools too. For example, students who don't do well academically usually stay quiet during class. But in philosophical dialogue, those same students suddenly start expressing their opinions clearly. Teachers are surprised when kids who rarely speak up suddenly offer well-thought-out views. What's valuable about this is how it changes perceptions of others. What was once thought as "this kid can't do it" becomes "actually, this kid is thinking deeply."

The same applies in companies. A junior employee who seemed unresponsive and unreliable at work might, the moment they engage in philosophical dialogue, clearly state their own opinions. This makes you rethink, "Actually, they are quite capable," and the relationship changes.

I believe that when human relationships form the foundation and individuals then take on roles, versus when people interact solely through roles without that foundation, the interpersonal dynamics within an organization change significantly. In that sense, philosophical dialogue in companies is relatively easy to introduce within a "team building" context. After the discussion, everyone shares a sense of enjoyment, fostering closer bonds. Many participants likely feel it genuinely helps improve the workplace atmosphere.

Nakamachi: For company employees, situations where roles are defined and acted upon are inevitably common. Thinking of team building as rooted first in mutual understanding and trust between people, rather than just business-like defined role division, makes me feel philosophy dialogue is a good fit.

Kajitani: Some companies now have managers holding one-on-one meetings with subordinates. But those typically take 30 minutes to an hour per person. I've heard feedback that using philosophical dialogue instead allows participants to gain a good understanding of ten people's personalities within just one hour. Moreover, it doesn't just change perceptions of subordinates; sometimes, views of the manager themselves shift. For instance, discovering that a boss you thought was extremely strict and nagging actually loves ice cream. It allows you to truly see the other person as a human being.

In philosophical dialogue, "cognitive safety" doesn't mean speaking without fear of being hurt; it means "any question is valid."

Nakamachi: Recently, the term "psychological safety" is often used in corporate settings. It's frequently applied to mean communication under a sense of trust where "you won't be blamed or scolded for anything you say." Honestly, though, I feel this term has taken on a life of its own lately. In communication, a state where people genuinely avoid hurting each other—I suspect most people haven't actually experienced that.

Kajitani: It's true that "psychological safety" is discussed not just in companies but across various organizations, and it conjures an image of everyone feeling comfortable, harmonious, and able to speak without fear of being hurt. Some people emphasize this as crucial in philosophical dialogue too. However, at least in the "safety" I learned about philosophical dialogue in places like Hawaii, the term used was "intellectual safety." Translated, this means "intellectual safety," meaning "any question is acceptable." It doesn't imply feeling comfortable speaking or that no one gets hurt.

In organizations, there are often situations where it's difficult to ask fundamental questions. If you ask "Why?" you might just get "Because that's how it is." Even in everyday conversation, asking too many questions can make people wary, wondering "Why is this person asking all this?" However, in philosophical dialogue, participants are simply exploring together with the pure purpose of wanting to know the reason or clarify the meaning of words. So, any question is valid; we just think about it together. That creates a certain sense of security.

Of course, depending on the question posed, the atmosphere can suddenly tense up with reactions like, "You're asking that?" But even then, no one says, "How dare you ask that?" That's the essence of philosophical dialogue: everyone properly receives and considers the question together.

Nakamachi: I see. So "intellectual safety" means that your intellectual curiosity—your thoughts and questions, no matter what kind—isn't stifled. It doesn't mean you can complain freely. What companies truly need is this "intellectual safety," isn't it?

Especially when generating ideas or creating something new, it's crucial not to be told "What nonsense are you talking about?" That felt like the essence of it.

Organizations made up only of top performers are fragile. Sometimes you need to question your own company's rules and incorporate the perspective of "less capable" people.

Kajiya: I believe a pleasant workplace is extremely important for working. That pleasantness isn't just about the work itself; ultimately, it's about human relationships. A workplace where you feel heard when you think, "Something's off here. Is this really okay?" should fundamentally be a comfortable place.

In companies, there's often a sense that the more capable people work hard, while it's understandable if others don't. But through philosophical dialogue, I feel each person has their own role, not just in terms of job duties. For example, there are people who don't speak much, just nodding and listening. Sometimes, it's precisely because such people are there that others feel comfortable speaking up. Conversely, you might see someone who speaks a lot, but you realize their contributions aren't particularly significant.

In this way, each person's presence and significance tends to become apparent. Even if someone isn't clearly "excellent," they can be surprisingly important. How companies actually evaluate people is a difficult issue, but I think it's possible for companies to recognize that people who seem inconspicuous or inadequate at first glance might actually be fulfilling very important roles. In fact, I suspect that organizations built solely on excellent people are actually quite fragile.

Nakamachi: It's similar to how a baseball team can't win games by just lining up cleanup hitters.

Kajitani: For instance, new employees often have little say because they must first learn the company's rules and mindset. But flip that around: precisely because they haven't been molded by the company yet, they're often the ones who notice its oddities first. The same goes for "ineffective employees" – in a way, they simply haven't adapted to the company's methods. While that might seem problematic at first glance, it raises the question: are the rules they're supposed to adapt to even correct? You could say these people are the most sensitive to that issue.

Nakamachi: It's true that people who can't perform well exist outside the organization's "norms," in a different culture. Rather than simply labeling them as "bad," it might be more beneficial for companies to consider how they can effectively incorporate the unique qualities of those outside the organizational culture. That might be what diversity is all about.

Kajitani: Diversity often becomes a situation where companies or schools push to accept people with different personalities. Efforts focus on making accommodations and improving facilities. However, the design world has a different perspective: "Extreme is mainstream."

This idea posits that if you create a space where those facing the greatest challenges can be "natural," everyone else will also feel comfortable. For example, elevators and escalators are fundamentally for people with physical disabilities, yet everyone else benefits from them. Tablets and keyboards were originally developed for people with physical or visual impairments.

If a company is comfortable for people who can't perform their jobs, it should also be comfortable for those who can.

An organization that embraces diverse questions will naturally foster transformation.

Nakamachi: Finally, from a philosopher's perspective, could you share any advice or insights for transforming Japanese companies and fostering co-creation?

Kajiya: In Japanese companies, evaluations tend to follow strict criteria, with rankings determined by those assessments. Those at the top are seen as good, while those below are considered unfortunate. Of course, some people strive because of these evaluations, and many argue that without coercion, people won't push themselves—that competition is what drives growth.

Nakamachi: That's true. I think that logic is particularly prevalent in the business world.

Kajitani: However, when I say it's good to have diverse people, I mean something slightly different from saying it's good to have people ranked from top to bottom in evaluations. In companies, the top and bottom are ultimately the result of cutting people based on the same standard. I believe we should stop ranking people according to a single criterion like that. While that kind of effort can achieve certain things, people strive because they find it interesting, feel recognized, or believe their efforts are worthwhile. Isn't trusting that aspect crucial?

This doesn't mean it's okay to be lazy or avoid anything difficult. There doesn't have to be just one standard, and we don't need to rank everyone constantly. Diversity is important because having different people generates diverse questions. If all those diverse questions are embraced, minor differences become acceptable, and society becomes more comfortable for everyone.

Philosophical dialogue lets you experience that feeling in just one hour. Understanding what it means to acknowledge different people, listen to their perspectives, and feel free to ask questions can transform how you work and build relationships. I believe "change" is a result. If an organization fosters an environment where everyone feels free to raise diverse questions, change will naturally emerge.