"First, let's generate lots of ideas and broaden our thinking!"

This is a phrase business professionals developing new products or ventures have likely heard at least once.

But what happens after you generate ideas?

Many people get lost after brainstorming and covering the wall with Post-its, unsure what to create next.

In this article, So Yamamoto of Dentsu Consulting Inc.—who has supported future-oriented strategy development and new business creation at numerous companies—and Yuhei Imai, a former Dentsu Consulting Inc. employee now at design firm kenma where he consistently creates hit products, explore how to elevate idea generation into a valuable process.

What mindset is truly essential for leveraging individual creative thinking in business settings—neither a mere list of random ideas nor rigidly formulaic organization?

The Limits of "Organizing with Frameworks"

Yamamoto: Mr. Imai, you're active as a business designer behind various hit products, including appearing on "Cambrian Palace" in March 2024. You were with Dentsu Consulting Inc. from December 2010 to September 2016, correct?

Imai: Yes. I joined Dentsu Consulting Inc. after working at a major design firm and other consulting firms. I feel like I'm in the same cohort as Mr. Yamamoto, who joined in the same summer.

Yamamoto: That's right. I think a common thread between us is the belief that it's crucial to fuse both the "logical stacking" typical of consulting firms and the "creative thinking" highly compatible with Dentsu Inc., rather than leaning heavily toward either one.

Imai: That's probably true. Since kenma's final deliverables are concrete products or services, purely consultative organization isn't enough. I see every day that simply organizing things into frameworks doesn't create anything new.

Yamamoto: Precisely, this idea of "merely organizing into frameworks" is a theme we must overcome as a consulting company within the Dentsu Group. Concepts like "framework thinking" and "MECE" are becoming commonplace in society, and we increasingly encounter clients concerned about whether something is "MECE." I feel that approaches traditionally considered quintessentially consulting are rapidly becoming commoditized.

Imai: In that case, simply organizing things in a formulaic way makes it harder for consultants to create value.

Yamamoto: Precisely why I believe incorporating unique perspectives into the thought process will become even more crucial going forward. Even when organizing using frameworks, it's not about forcing things into pre-made boxes. We must first answer the question: "How can we create the framework itself tailored to that specific situation?" It's certainly not easy, but I view it positively as a necessary step for delivering fundamental value.

Is Simply "Generating" Ideas Insufficient!?

Imai: This idea of creating frameworks while delivering unique value aligns with the message I wanted to convey in "Amazing Ideas," published this February.

Yamamoto: I had the chance to read it, and it was fascinating. This book explains "what makes an idea great" through reproducible formulas and concrete examples, overlapping with James W. Young's classic "A Technique for Creating Ideas" on a similar theme.

Great Ideas: The Formula for "Selling with Edge" Business Thinking

Written by Yuhei Imai / Shodensha

Imai: Exactly. My initial concept was to write a Reiwa-era version of that book. On top of that, what I really wanted to emphasize was

"Ideation" is great, but isn't "judgment" and "measurement" also crucial?

Even if you generate tons of ideas, if you don't have a clear process for narrowing them down, they'll never take shape as a viable business.

Yamamoto: It's true. While there are many books on "idea generation," there aren't many that guide you on "idea evaluation."

Imai: Often, it boils down to talk about how "sense" is crucial, or ideas are judged solely based on the size of the accessible market. That's precisely why in "Great Ideas," I wrote about how defining the "requirements" an idea solves is essential, and that an idea is truly great when it clears those requirements all at once.

Yamamoto: Among the examples in the book, the "Morning Bottle" idea that hits all the requirements at once really stands out. By renting out bottles for cold-brewed green tea outside stores during the morning commute, it simultaneously expands the target audience and creates a societal buzz.

The hit product "Morning Bottle," developed by Nagoya's Japanese tea cafe "mirume (Mirume) Fukamidori Sabo" in collaboration with kenma. It features cold-brewed green tea in a glass bottle (300ml), allowing users to enjoy up to three infusions by refilling with water.

Imai: I believe the key to its success was concretely defining "success." When aiming for "sales," how vividly can you describe the specific events that would occur upon achieving them? Things like who is using it or which media outlets are featuring it.

If you can paint a high-resolution picture of the state of success, the points you need to consider become clearer. This process is nothing other than "creating your own framework."

When you clearly define "this is the goal to achieve in this project," it simultaneously establishes the overall picture you need to consider now. Reaching that state also reduces the likelihood of getting bogged down in debates about whether something is MECE or not.

Yamamoto: Having criteria for evaluating ideas and concretizing the image of success – I strongly agree with both. In Dentsu Consulting Inc. projects, we often use tools like the "Dentsu Future Mandala" to expand ideas about future society and consumers before deriving business ideas and strategic points. In those cases, we always structure the process to include "convergence" alongside "divergence."

Imai: That's great. When people talk about "idea generation," I think it's undesirable to focus solely on expanding. I tend to be pretty strict with people who feel like they've done their job just by generating a lot of ideas (laughs).

Yamamoto: It's a waste to just keep expanding without direction. When defining the conditions for convergence, we invest time in building consensus with the client.

Also, it's crucial to clarify "what we ultimately want to achieve" right at the start of the review phase. In business settings, abstract language tends to dominate, and concrete discussions often get sidelined.

If we can define the goal beyond a general phrase like "growth in XX" to include "who, where, in what mood, and how it's being used," the path forward becomes clear. This allows everyone involved to move forward without hesitation. I'm always mindful of how to navigate between the concrete and the abstract.

Imai: However, one thing to be careful about is that even though defining success is important, asking a client, "What is your definition of success?" doesn't necessarily guarantee a clear answer.

Yamamoto: Exactly. I think we need to hold hypotheses while combining multiple questions to pinpoint the precise goal.

When gathering information, "Don't start with the issue."

From left: Dentsu Consulting Inc.'s So Yamamoto, kenma's Yuhei Imai

Imai: You mentioned "having a hypothesis," but I imagine people have different styles for creating a well-founded one. In my current work, I don't really do much "researching the industry."

Yamamoto: Really? That's surprising.

Imai: I believe it's important to acknowledge that "there are things I don't know." I focus on clearly understanding what I don't know and then ask the client questions about those gaps. That's the process I use to refine my hypotheses.

Yamamoto: I see. I probably don't start with a "research first" process either. When thinking about the value chain, we often say things like "create, make, sell." But if you first organize things within that framework—where value is created, how the actual product or service is assembled, and how it's delivered—you can start to imagine the industry structure. I often think that far through before starting research to fill in the gaps.

Imai: So you mean there's a kind of thinking template?

Yamamoto: Yes. But what you just said made me realize—perhaps what creates that "thinking pattern" is the massive input that comes before it. I'm kind of an "information junkie," the type who can't relax unless I'm listening to a podcast or something, even during those few minutes of getting ready (laughs).

I feel like the information I'm constantly exposed to daily—whether business-related or not—accumulates within me. When a work-related theme is thrown into that mix, it sparks a "hypothesis."

Imai: I'm not really interested in much outside of work (laughs), so I might be quite different in that regard. My approach is more like becoming deeply interested in a subject when a project starts, then grasping the crucial points from the limited information available.

Yamamoto: In consulting, there's the saying "Start with the issue." Because you have to deliver answers within limited time, it encourages focusing on the most critical questions. But when it comes to daily input, I actually think "Don't start with the issue" is more important.

Imai: So, not being too fixed in your thinking is the source of value, right?

Yamamoto: Research starting with issues is efficient, but it often leads to "ordinary conclusions." In fact, such information gathering will eventually be handled by AI. Precisely because of this, I believe it's crucial to constantly engage with diverse information to cultivate your own perspective on the world—your , or worldview.

Consulting Evolves Through "Want" and "Subjectivity"

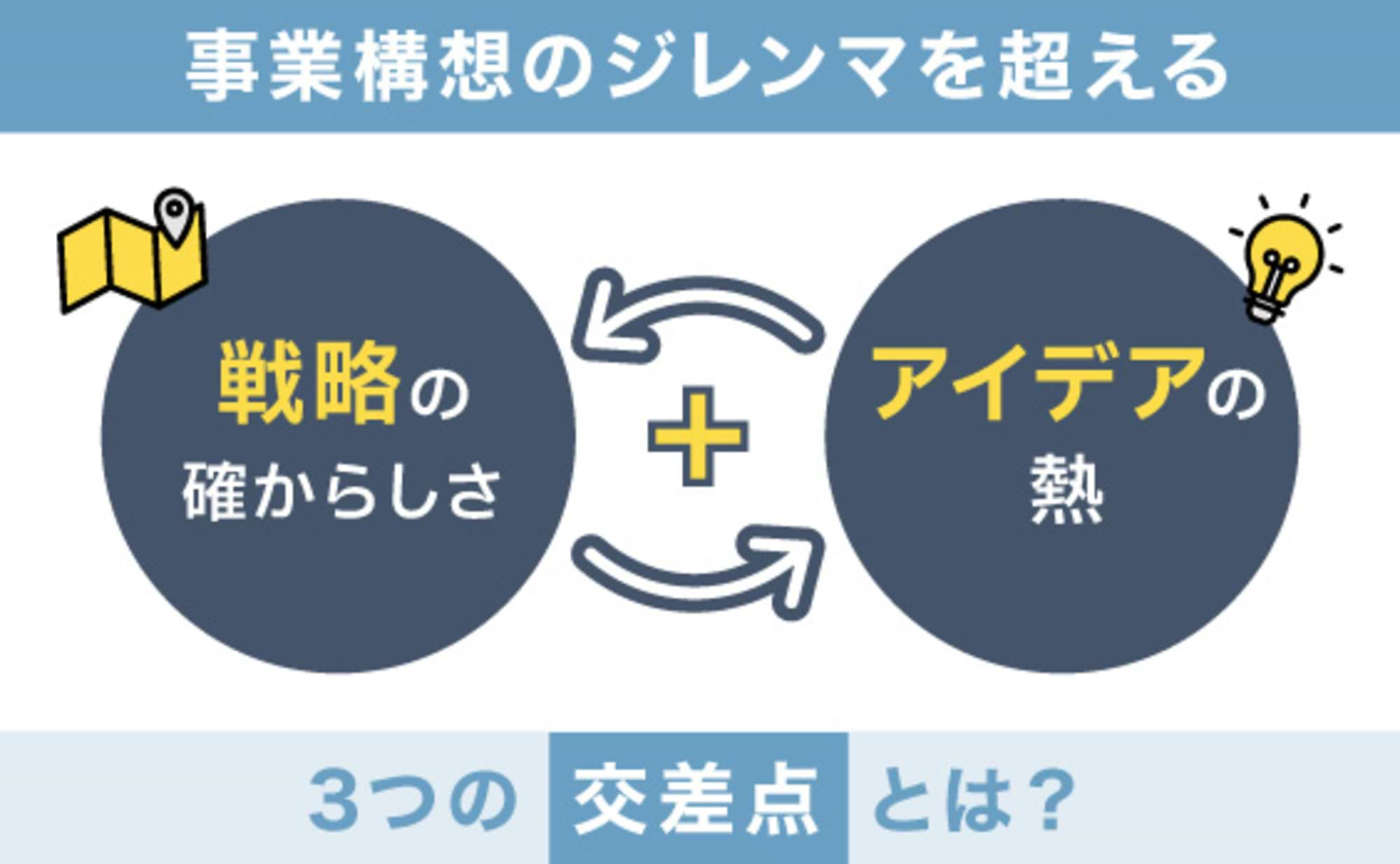

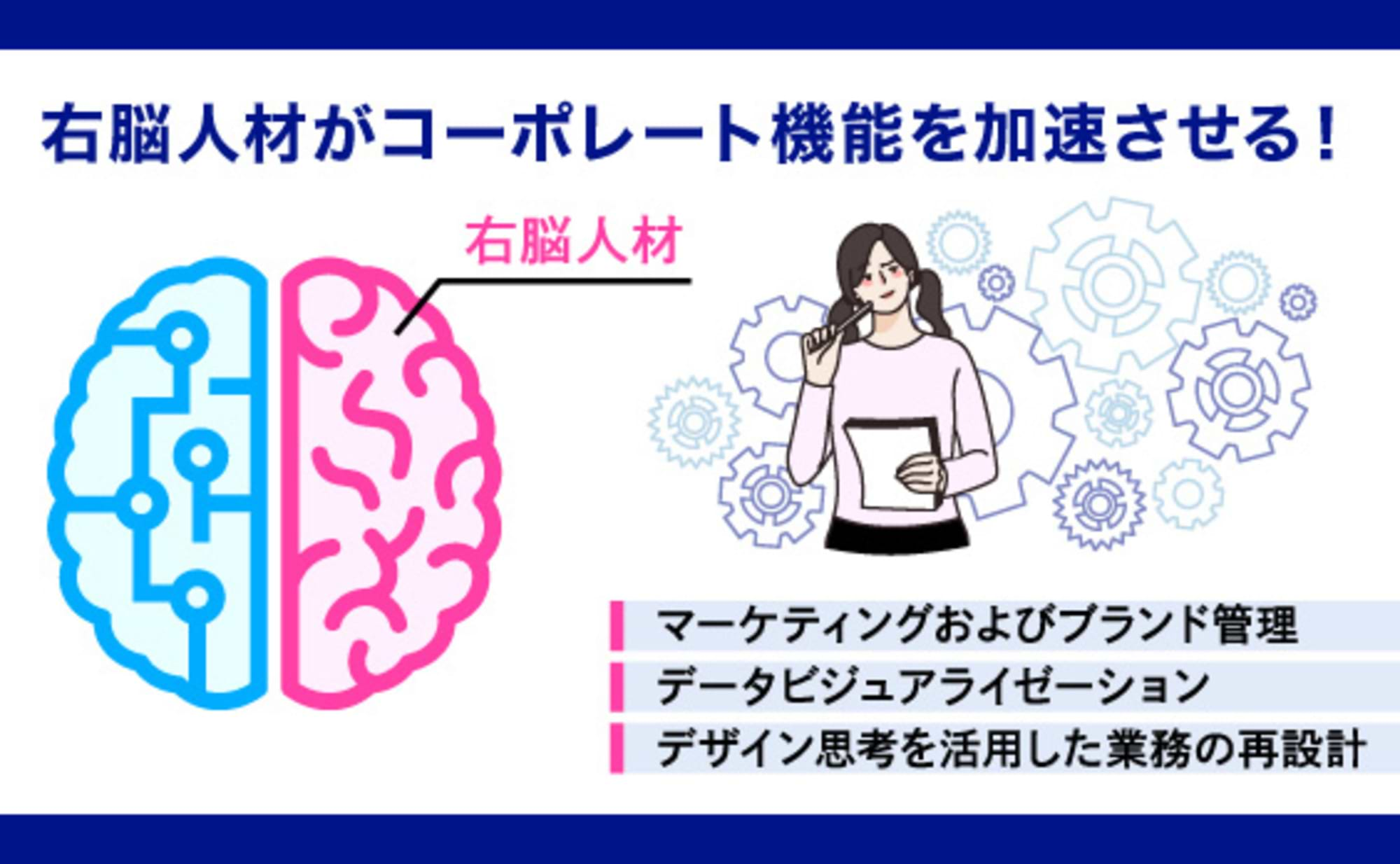

Yamamoto: From your perspective, Imai-san, if you have any insights on how to make what's called consulting work more relevant to today's times, I'd love to hear them. At Dentsu Consulting Inc., we champion "unique certainty" or "right brain × left brain × extraordinary talent," aiming for outputs that move people beyond just logic.

Imai: Well... Looking back, I think I used to be like that too. As consultants, we tend to focus on "musts" and overthink things. "The market is like this, so we should do that," or "The competition is doing this, so we have to do that." While that's certainly important, if you're aiming for uniqueness and creativity, I think it's difficult without also addressing "wants."

Yamamoto: So it's about valuing "this is what we want to do" and "this would be great if we could do it," rather than just "this is what we should do" or "this is what we must do."

Imai: The other day, I had the chance to see the final report from a well-known consulting firm. It was very well put together, and I thought, "Wow, that's impressive." But at the same time, I felt a bit stifled by the strict rule that "only facts can be written."

Yamamoto: I see. As someone who works in consulting, that dilemma is painfully familiar (laughs).

Imai: While it's natural that many situations require solid facts, it's crucial to remember that relying solely on facts won't produce anything truly interesting.

Yamamoto: That's very insightful. Lately, in seminars and articles, I've been advocating a concept I call "New Consulting Thinking." I'm interested in how we can expand the consulting thought process, which often leans too heavily toward "factual correctness" and "overview-based organization." I see a direct connection to what you just pointed out.

Simply put, "New Consulting Thinking" is illustrated in the diagram below.

Imai: Indeed, to arrive at answers different from the increasingly generalized consulting mindset, "does it excite you?" is a crucial point.

Yamamoto: Yes. And that "excitement" starts from personal subjectivity. "New Consulting Thinking" calls for valuing not just logical organization, but also those moments that truly resonate with you as an individual living your own life. By properly incorporating individual subjectivity—often overlooked in consulting work—into the deliberation process, we believe the quality of the output will improve.

Imai: I agree. In "Great Ideas," we emphasized the importance of the "desirer." Do people genuinely exist who would pay their own money for this idea? At the idea-generation stage, I believe having even one such desirer is sufficient. The key point here is not to immediately jump to "What percentage of people want it?" Instead, by deeply exploring why they want it and what value it holds for them, the strength of the idea becomes more robust.

In terms of considering whether it sparks excitement and avoiding hastily introducing a bird's-eye perspective, there may be some overlap with "New Consulting Thinking."

Yamamoto: Prioritizing excitement while advancing discussions positively impacts project team motivation. Perhaps because of this, we often hear feedback like "Working together helped me grow" from projects with Dentsu Consulting Inc.

Imai: That's wonderful. Since kenma's work is product development, the final product created becomes the company's focal point. In that sense, I imagine it's not easy to draw out motivation within the client company in consulting projects, which don't necessarily produce a visible product.

Yamamoto: What the project members want to do, and what will get them personally excited beyond just the company's success—that sense of purpose is actually crucial. We've gradually built up insights into project design that doesn't neglect that perspective. Moving forward, we want Dentsu Consulting Inc. to increase the number of projects that balance business soundness with that sense of excitement.