In the early 1990s, a foreign employee stationed at an advertising agency in Moscow would often approach his Russian colleagues' desks and ask, "Hey, why does every single Russian have the same books?" The Soviet Encyclopedia. Mayakovsky. Tolstoy. Victor Hugo. Jules Verne. Ideology painted bookshelves a single color, and the state-controlled economy produced identical goods. Nothing else was to be found. From furniture to children's toys, everything was exactly the same.

Now, when we go to an IKEA store, we're overwhelmed by the sheer variety of products. It's unimaginable that 30 years ago, my parents' generation would gather scraps of wood from around town to build a dresser by hand, then invite neighbors over to show it off. Masterpieces of everyday life were crafted by amateur artisans back then.

Creativity is born when confronting adversity. It thrives despite the uniformity of the landscape and the lack of detail. An unchanging environment can sometimes foster the most passionate creativity. A man raised in the Ural countryside smashed teapots and plates to decorate his home. I later learned that creativity like his existed in another world. When Russians could finally cross borders, I visited Barcelona and witnessed Gaudí's architecture. How could a craftsman in the Ural, in an era without access to information, have built a house inspired by the same ideas as Gaudí?

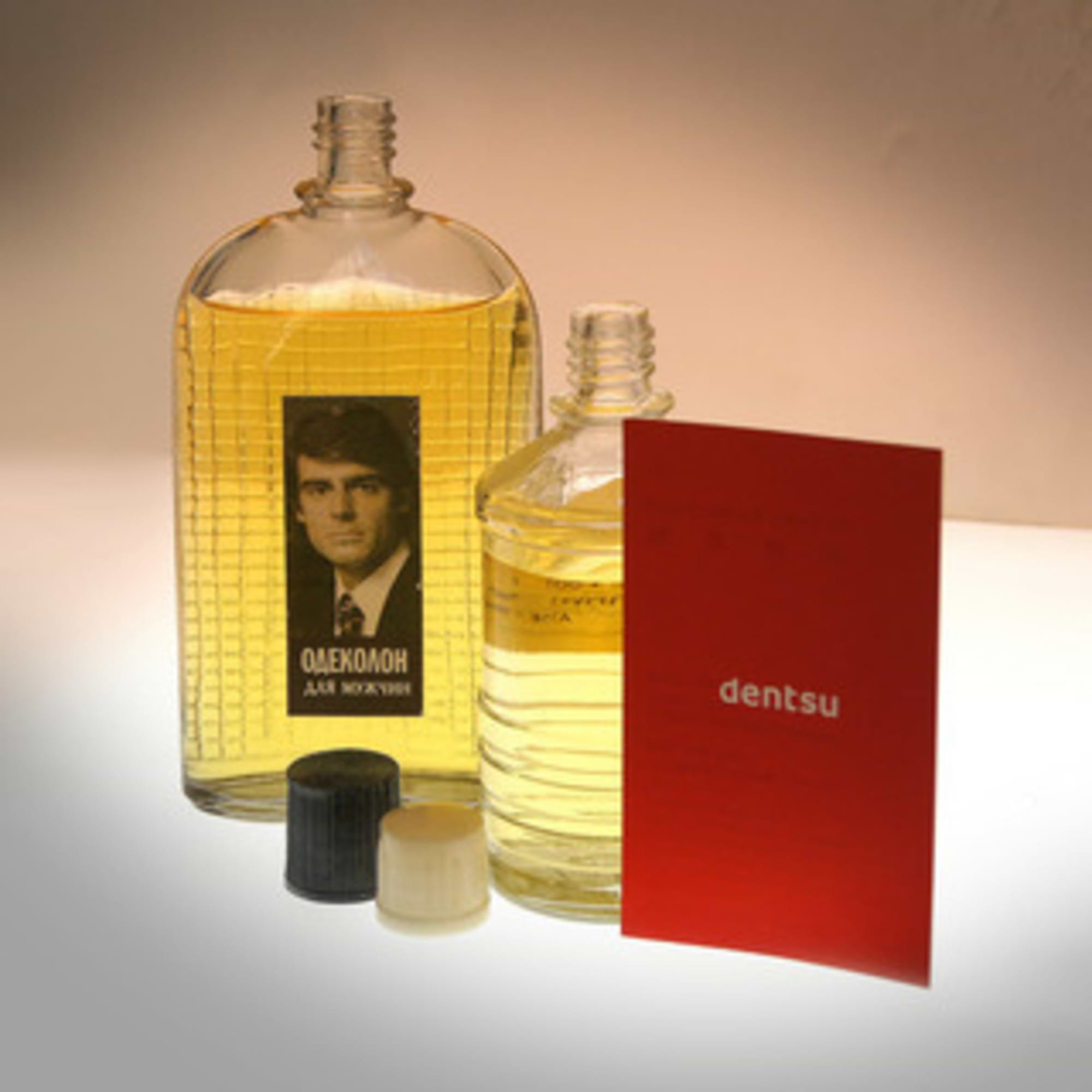

Children play with whatever they can get their hands on. Perfume bottle caps were especially popular. We'd remove just the caps from my father's cologne or my mother's perfume and play, giving them names of our own: "Baby Elephant," "Officer," "Festival."

Tracing back to childhood memories brings me to this scene. I was a five-year-old boy. My late grandmother's old house. Grandmother and I were making toy cars. Using what might have been a plow handle, she sawed a log into wheels, slicing it like a sausage. She heated knitting needles over the gas stove and burned spoke patterns onto the wooden wheels. A perfume box transforms into the car body. We rolled brown clay into a ball for the driver's head, placed it on the body, and it was complete.

I no longer remember what the finished car looked like. What I still recall is how excited I was by the process of creation—that process itself was magic. That magic remains magic to this day. Children raised in the 90s amidst colorful books, furniture, and toys have grown up and started working in the Russian advertising world. In a few years, they will completely replace our generation, who played with perfume bottle caps.

(Supervised by: Dentsu Inc. Aegis Network Business Bureau)