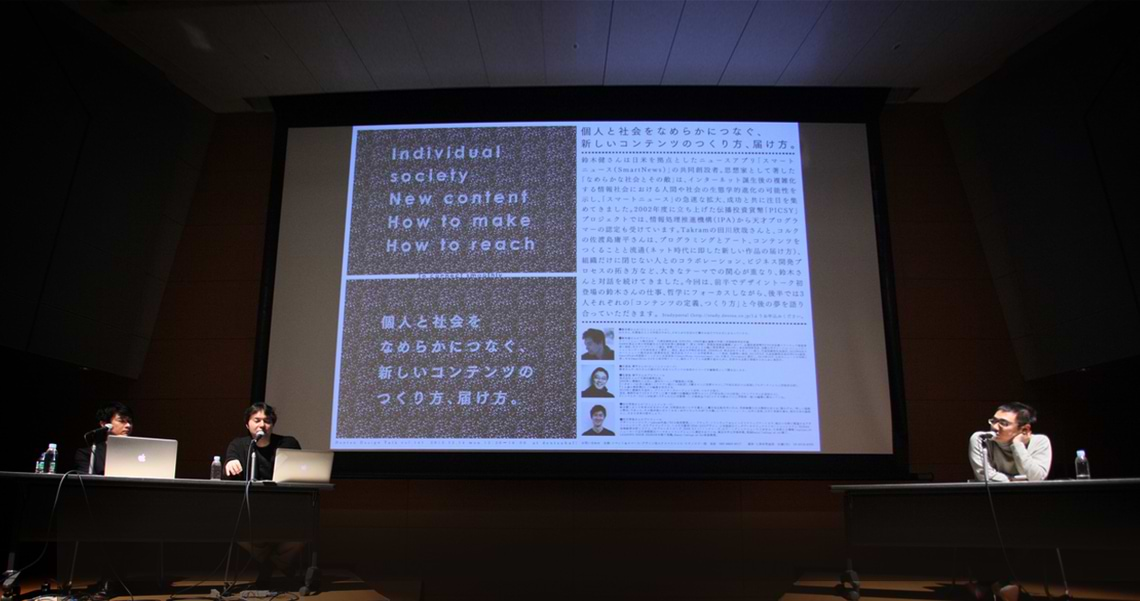

Film director Miwa Nishikawa, who has produced hit films like "The Long Excuse" and " Dear Doctor," is currently filming her own Naoki Prize-nominated work " The Long Excuse " (scheduled for release in 2016). Copywriter Masakazu Taniyama, who assists with promotional copy for her films, facilitated this conversation between the two. Moderating the discussion is Shinichi Fukusato of One Sky, who has worked extensively with Mr. Tanigawa and is also a fan of Ms. Nishikawa's films. What does it mean to think? How does the brain generate ideas? They traced their respective creative processes while discussing these questions.

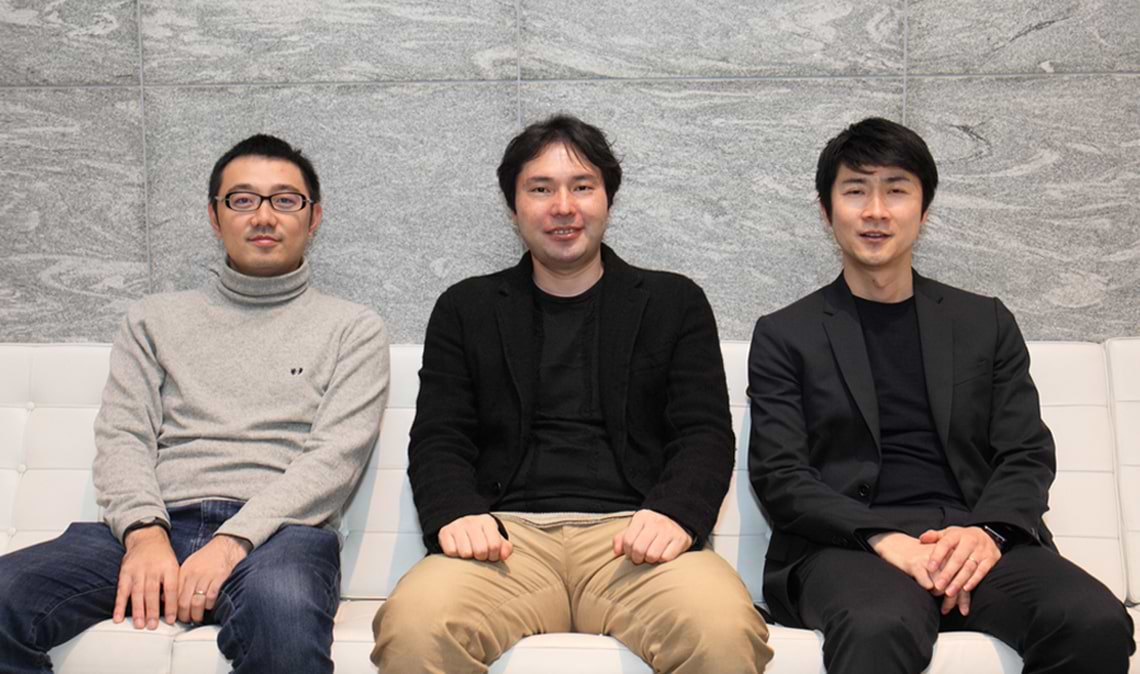

(From left) Mr. Tanigawa, Mr. Nishikawa, Mr. Fukusato

Mr. Taniyama ⇔ Mr. Nishikawa: 5 Questions

"Is it true you get inspiration for your films from dreams?"

Fukusato: Mr. Nishikawa, you consistently create films that become major topics of conversation. Last year, your novel The Long Apology (Bungeishunju) was nominated for the Naoki Prize. Now, you're personally working on its film adaptation, right?

Taniyama: This talk came about because I had the opportunity to write the tagline for that film, The Long Apology. Today, our theme is "thinking about thinking." We'll proceed by asking each other questions.

Fukusato: Director Nishikawa, what was your impression of Mr. Tanigawa?

Nishikawa: I thought he was exceptionally skilled at explaining concepts. My field of work doesn't involve "presentations." In filmmaking, you develop a project into a plot or script, hand it over to the producer, and then the producer presents it to various parties... That's the flow. So, I'm not accustomed to, and actually feel uncomfortable with, articulating "how wonderful my own ideas are" to people in my own words. People in the advertising field have honed their thinking and training in "how to communicate," so working with such individuals is very stimulating.

Fukusato: First, a question from Mr. Taniyama. "I'd like to ask about how you get started with ideas. You mentioned in a previous interview that you often draw inspiration from scenes you see in your dreams. Is that true?"

Taniyama: I heard the film "Sway" came from a dream you had where a friend was killing someone?

Nishikawa: Both my first film, 'Snake Strawberry,' and my second, 'Sway,' were definitely inspired by dreams. For 'Sway,' I dreamt that a male friend, while hiking deep in the mountains, tried to help a girl he liked by reaching out to her, but she pushed his hand away. Enraged, he pushed her into a waterfall pool. I witnessed this from behind some bushes. Since he was my friend, I thought if I kept quiet, it could be covered up as an accident instead of murder. But as I tried to make it look like an accident, both he—who was a good person—and I started to go completely mad... That was the dream.

Taniyama: Was it really just a dream? It sounded like you were summarizing a story.

Nishikawa: I really saw it, woke up drenched in sweat. I thought the relationship between the two protagonists needed to be tighter, a bond they couldn't escape from each other's lives, so in the film I made them "brothers."

Fukusato: Why did you have such a dream?

Nishikawa: Why did I have it...? Slowly, I often discover fears I've suppressed deep within myself, or aspects I want to hide, through my dreams. On the flip side, what kind of dreams do you all have?

Fukusato: I don't dream at all.

Nishikawa: Heh heh heh.

Taniyama: Mine are disjointed and I forget them right away.

Nishikawa: That's usually how it is for me too. That's why I started writing them down. But after the first and second works, where the story came together nicely in my dreams, I thought maybe I could keep making a living from dreams... and then I stopped having them altogether (laughs).

Taniyama: So it wasn't that easy?

Nishikawa: They haven't been very good since then (laughs).

Fukusato: Since we're here, could I ask about Dear Doctor?

Nishikawa: My second film, 'Swaying,' was a small production but became a hit and received high critical acclaim. I'd just turned 30 at the time, and people started calling me the rising star of Japanese cinema. The pressure was immense. I couldn't possibly see myself that way, and I felt like society just wanted to turn a fake into the real thing. That's why I wrote the story about the fake doctor.

Fukusato: I see. So your own fears were the starting point there too.

Nishikawa → Question for Taniyama: "Doesn't the appeal of a simple idea become blurred the more you keep thinking about it?"

Fukusato: Next is a question from Nishikawa-san: "Reading Taniyama-san's books, you often see phrases like 'writing 100 or 300 copy pieces in a single night.' For example, an extremely simple phrase like 'Japanese women are beautiful.' At what stage did that come about? Doesn't the appeal of a simple idea get buried or blurred as you focus on quantity?"

Taniyama: Great ideas usually come within the first 10 or right at the very end. For TSUBAKI's "Japanese women are beautiful," it might have been the zero-th draft. By zero-th draft, I mean "Japanese women are beautiful" was the product's core theme. Back then, shampoos targeting Asian beauty or Hollywood beauty were selling well, leaving a gap for a shampoo positioned squarely around Japanese women. That's how TSUBAKI was born – to create a brand that consistently says "Japanese women are wonderful, beautiful." When you write the first draft, you think "This is pretty good!" for a moment, but then doubt creeps in. As you keep writing more drafts, like trying out different calculations, you eventually realize, "I wrote so many, but the first one was actually the best," and that doubt disappears.

Nishikawa: I also rewrite scripts extensively. But when you add and subtract various elements, and that process expands, you often lose the courage to return to something simple.

Fukusato: I heard you rewrote the script for 'Sway' so much that actor Teruyuki Kagawa asked you to "go back to the previous version."

Nishikawa: That's right. He said, "I know it's not right for an actor to say this to a director, but if an actor gets three chances in life to speak up to a director, I'm playing one of those cards," and asked me to revert to the script from two versions prior.

Fukusato: Mr. Kagawa is so cool.

Nishikawa: He really is. He pointed out that as I tried to pack all sorts of explanations into the dialogue logically, the flow and explosive power of the emotion itself weakened in direct proportion. When I reread the first draft, I realized how simple it actually was.

Taniyama → Question for Nishikawa

"When you handle the original work, screenplay, and directing all by yourself, how do you switch your perspective?"

Fukusato: Now, from Mr. Tanigawa. "When you handle the original work → screenplay → directing all by yourself, do you experience changes in perspective or way of thinking at each stage?"

Taniyama: If it were someone else's original work, you could objectively decide, "This part isn't needed, so let's cut it." But when you're adapting your own original work as a screenwriter or director, isn't it harder precisely because you're the only one involved?

Nishikawa: I believe what's achievable in text differs from what's achievable in film. A screenplay is a blueprint for visuals, but an original work can include elements that don't need to be visualized. By writing without imposing the constraint of visualization on myself, I aimed to give the characters and story foundation more depth and to understand them better myself. That was my purpose in writing the original work this time.

Taniyama: When I read the original novel, it didn't feel like it was written with a film adaptation in mind at all. It had a high level of completion as a novel. So this time, you were very conscious of that?

Nishikawa: Yes. I usually write the film script first, but I felt incredibly constrained by having to write the story only within the limitations of budget and other factors. With The Long Excuse, I wrote the story free from those constraints. If I aimed for a faithful visual adaptation of the original work, the cast would inevitably differ from the characters I imagined when writing it, and the locations would be different too. Being bound by the original work makes me perceive those differences negatively. So, when adapting it for film, I consciously tried to be the one among the staff and cast who forgot the original work the most.

Fukusato: How was it for you to translate such vividly described psychological states in prose into moving images?

Nishikawa: Expressing a person's inner world visually is incredibly difficult. It's not as simple as just using a monologue. For example, even trying to depict what a small child is thinking visually often doesn't work well. That's why I think the world of words is so fascinating—it allows for such free expression. I treat writing the original work and adapting it for film as entirely separate tasks. I build each scene one by one, constantly thinking about what only film can achieve. Rather than trying to skillfully rewrite the original into a script, I focus on substitution: how can I convey that feeling by moving a character? Instead of just having them say it, might a single shot of a telling landscape make it "visible"? This approach keeps each task fresh and prevents boredom.

You can also read the interview here on AdTie!

Planning & Production: Dentsu Inc. Event & Space Design Bureau, Aki Kanahara