Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

Hints revealed from the survey results on U-turn migrants

Population Decline and the Reality of Tokyo's Centralization

How aware are you of the severity of population decline?

According to the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan's population decline began in 2008. At the current birth rate, the population is projected to reach 97 million by 2050, halve to 52 million by 2100, and further decline to 14 million in 200 years and 4 million in 300 years. Japan faces the risk of disappearing as a nation. The population decline in rural areas will accelerate first. By 2050, it is estimated that over half the population in 60% of inhabited regions will be halved, and one-third of those areas will become uninhabited. This is what is termed "regional extinction."

Amidst this rural population decline, the most pressing issue today is the extreme concentration of people in Tokyo. Although the national government has long implemented measures to address this, the flow of people from regional areas to the Tokyo metropolitan area (Tokyo and the three surrounding prefectures) shows little sign of stopping. Furthermore, it has been revealed that the net migration surplus to the Tokyo area is dominated by just 64 municipalities, including Osaka City, Nagoya City, Sendai City, Sapporo City, and Fukuoka City, accounting for 50% of the total (Figure 1).

While core cities in regions are expected to act as dams against population outflow to the Tokyo area, they have instead functioned as pumps, drawing people from nearby areas and sending them to Tokyo. Tokyo, swallowing up populations from the regions, can be described as a black hole, accelerating its own population decline due to its overwhelmingly low birth rate.

First Survey on the Reality of "U-Turn Migration" as a Stimulant for Tokyo's One-Pointed Concentration

Could promoting "U-turn migration" be an effective way to resolve this Tokyo-centric concentration? Based on this idea, Dentsu Inc.'s Regional Revitalization Office conducted a survey last November targeting over 1,700 actual U-turn migrants nationwide to quantitatively understand their circumstances.

Survey Method: Quantitative web-based survey

Survey Participants: Men and women aged 20s to 60s who actually relocated back to their hometowns nationwide: 1,714 individuals

※ Excludes external factors like job transfers / Outflow from Tokyo (Tokyo Metropolis and three neighboring prefectures) to the top 64 U-turn destinations

Survey Period: October 19 - November 6, 2017

The reality of U-turners: "Average age 37. Single individuals"

The pre-survey hypothesis was that the typical image of a returnee was a "senior couple." The assumption was that they were "people who originally moved to Tokyo for work, nearing retirement age, and experiencing a growing longing for their hometown. Their children have become independent, and the couple is now free to move. Many return to southern regions, seeking a slower pace of life" (Figure 2).

However, the actual survey revealed this was a significant misconception.

◍ Not senior couples, but "single individuals with an average age of 37."

◍ They moved to Tokyo for "school enrollment," not employment.

◍ Not nearing retirement, but "in the prime of their working lives."

◍ The trigger was "stress from Tokyo life" rather than homesickness.

◍ Not children who have left home, but a stage where they still want to "live near their parents' home."

◍Not the south, but the north.

◍Not seeking a slow life, but "an office worker changing jobs to another company."

It means: "People who moved to Tokyo out of longing find that once Tokyo life settles down and the novelty wears off, they realize the metropolitan area isn't a place they can live forever." "As stress builds from Tokyo's hectic pace and relationships, they choose to return near their parents" (Figure 3).

The biggest barrier to returning home is "work and money"

It was also found that the biggest barrier to returning home was "work and money." This remained a source of anxiety not only during the consideration phase, but from the moment the decision was made until the present after returning home, when there was no turning back (Figure 4).

Furthermore, when considering future drivers of regional revitalization, the "younger generation" holds the potential for population growth. Looking at the 20-35 age group,

◍ They move to Tokyo driven by a stronger longing for the city and a stronger dissatisfaction with their hometown.

◍ They experience greater stress from Tokyo life, their parents worry more, they themselves want to live closer to their parents, and their love for their hometown grows inversely proportional to this.

◍Regarding U-turns, they deeply worry about jobs and money, and lack information for relocation.

This reveals a reality marked by deeper struggles.

But are those who made the U-turn happy!?

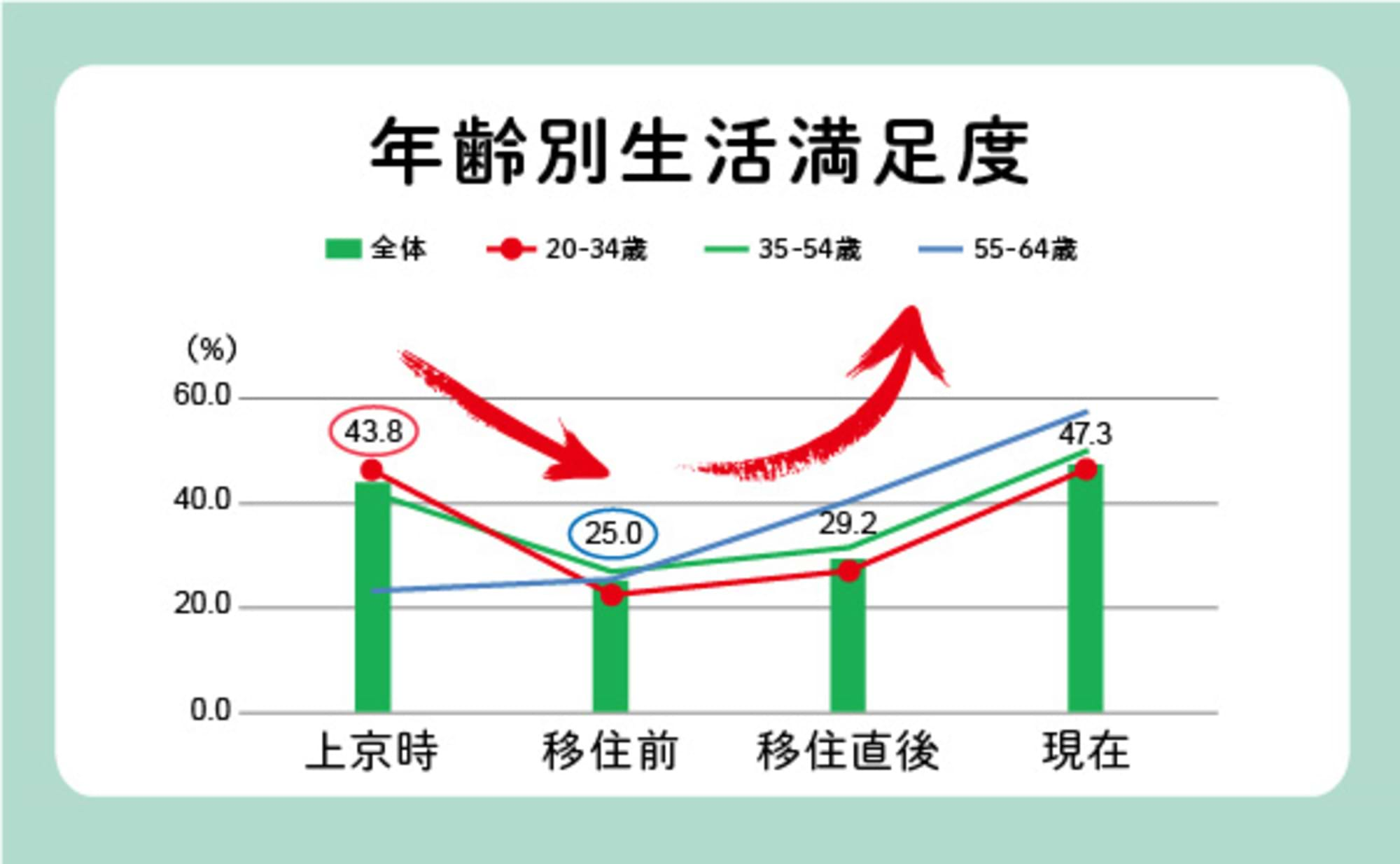

While worries are inherent to returning home, the biggest discovery of this survey was that people who successfully returned home, including younger generations, reported higher life satisfaction than before (Figure 5).

This chart shows the percentage of people who rated their life satisfaction as 8 or 10 on a 10-point scale—indicating a high level of satisfaction—over time, up to after their return. The bar graph represents the overall population, while the red line graph shows the younger generation.

Upon moving to Tokyo, over 40% expressed high satisfaction, their dream of living in the capital fulfilled. However, while in Tokyo, stress from city life caused satisfaction to plummet. Yet, even so, the data shows that after returning home, their life satisfaction is higher than it was when they first moved to Tokyo.

In other words, likely driven by the stress of Tokyo life, they returned seeking life near their parents and in their nostalgic hometowns. While this might seem like a somewhat defeated return, many are now liberated from stress and find themselves "happier" in their nostalgic hometowns than when they first arrived in the coveted Tokyo.

Many people are still hesitating to make the return move for various reasons. But those who have already made the move are "happier." We believe this presents an opportunity to activate the potential pool of people still hesitating about returning.

Three Hints for Activating the Potential Returnee Pool

Looking at these survey results and the group interviews conducted by Dentsu Kyushu Inc. prior to this survey, three things appear necessary to activate this potential U-turn population.

1.Currently, both their own assumptions and the perceptions of those around them are somewhat negative.

Change the image of young returnees and create an environment that encourages return migration.

Create an environment to encourage U-turns.

2.When considering a U-turn, increase opportunities to "visualize life after returning" in specific situations

and provide insights.

3.And when they finally decide to return,

access to information about "jobs," which is the biggest hurdle.

Among various migration types, U-turns possess the strength of a connection to one's hometown and can serve as a catalyst for regional revitalization. There is still a large potential pool of people. However, as things stand, most of them will not actually make the move. According to a Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications survey, while one in three people express a desire to relocate, only around 1% have actual plans to do so.

How can we bridge this gap between aspiration and reality?

Why do various promotion measures implemented by local governments struggle to yield significant results?

In this three-part series, we will examine the findings of the first survey on the actual state of U-turn migration. In the second part, we will look at the changing values of today's youth to accelerate U-turn migration. Finally, in the third part, we will present hints (policy ideas) for activating the potential U-turn population as we envision it.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Author

Junji Hirokawa

Dentsu Inc.

Regional Innovation Center Regional Revitalization Office

Senior Marketing Manager

Joined Dentsu Inc. in 1987. For 30 years, engaged in corporate strategy, product development, and communication strategy planning for various companies and organizations across industries including food, beverages, mobility equipment, pharmaceuticals, banking, and precision instruments. Since 2016, has worked in the Regional Revitalization Office, focusing on tourism strategy and industrial promotion for local governments.