Children measure time by "events," not clocks

Children simply refuse to move according to adult time. Even if you say, "You'll be late for daycare!" they'll still dawdle over breakfast. Even if you say, "The train's leaving!" they'll keep rolling their pill bugs. At parks or toy stores, you see parents everywhere pleading with their unmoving children, "Let's go eat lunch now," or "It's already 5 o'clock. We really should head home," only to fail time and again. Why are these mysterious creatures called children so relaxed (?) about time? What kind of time do they live in?

This time, we welcomed Professor Makoto Ichikawa from Chiba University, a researcher in "time studies," to discuss the differences in time perception between adults and children with Fumiko Ishida and Mitsuhiro Kutsukake from the Children's Perspective Lab.

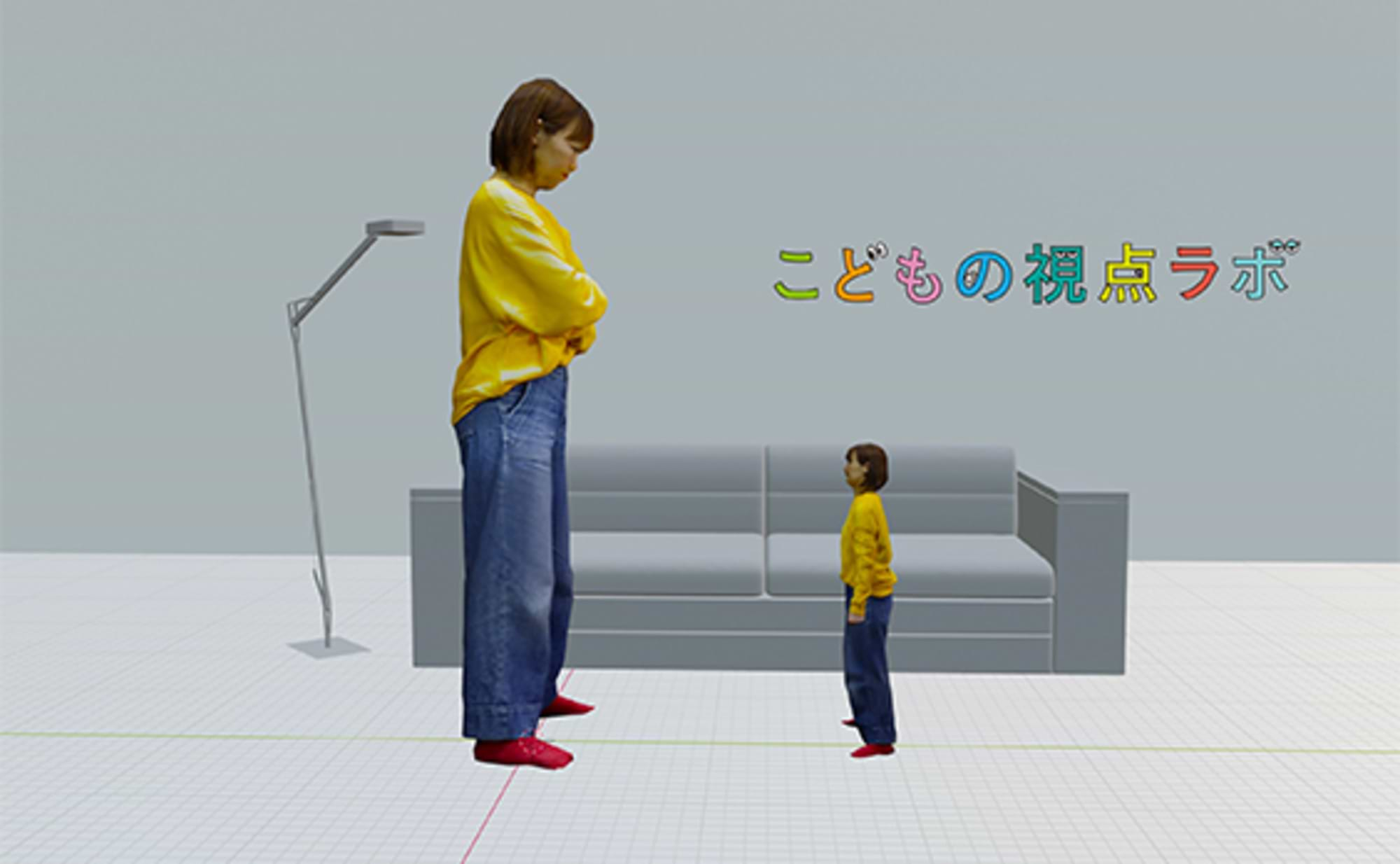

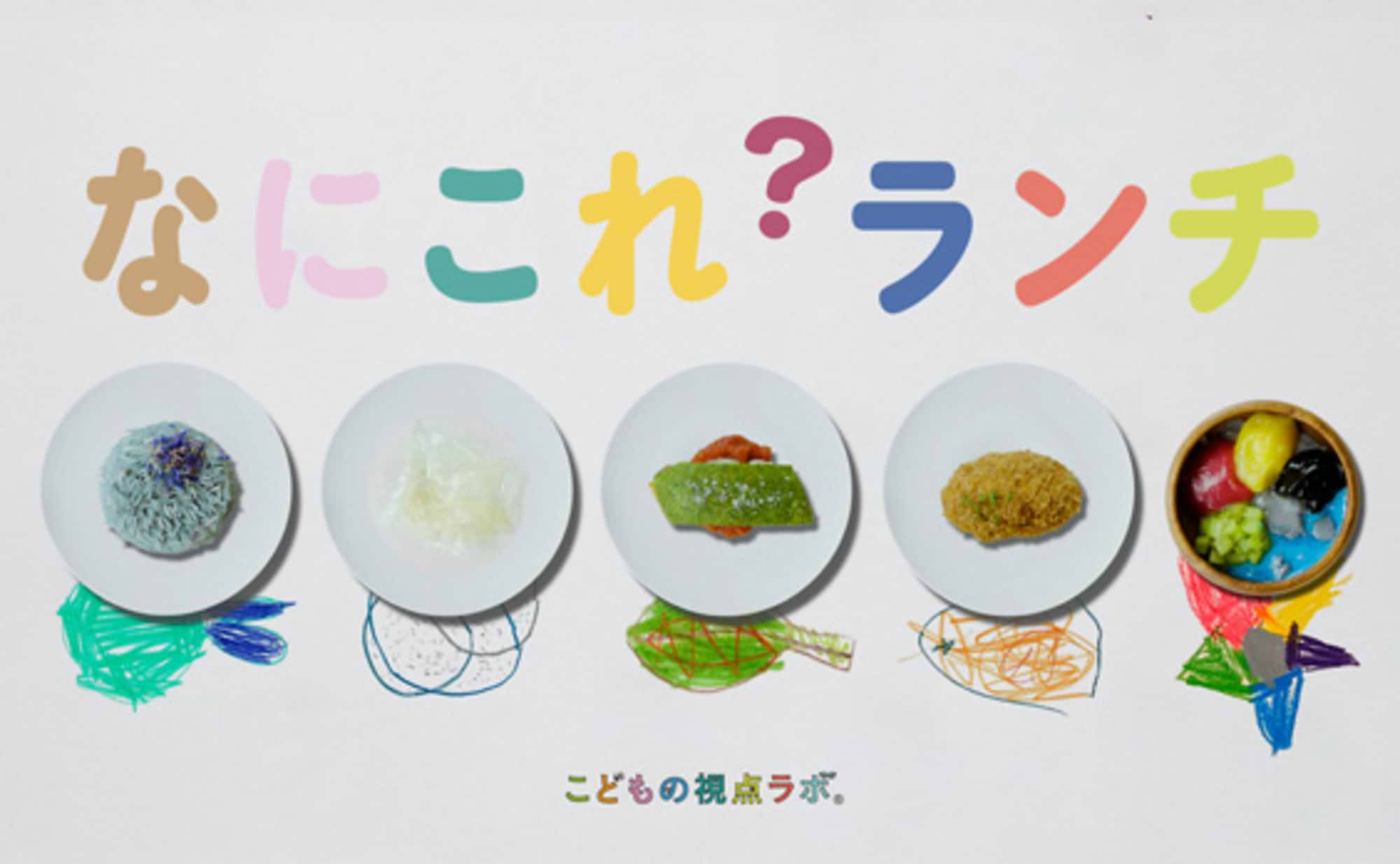

Ishida: The Children's Perspective Lab conducts activities to understand children by "adults becoming children." But this time, we didn't know how to experience children's time, so first, we visualized "children's time" with photographer Tenten (the photo work at the beginning).

Kutsukake: This work by Tenten captures the morning routine of her child, Ito-chan (age 4 at the time), using a fixed-point camera, condensed into a single photograph. While the mother seemed to be moving back and forth between the kitchen and dining table, Ito-chan was doing so many things: playing with the cat, playing with various toys, climbing on the desk and sofa, watching TV, and even fooling around while getting dressed.

Ishida: There's a park version too, right?

Kutsukake: Yes. This one is 30 minutes at the park. She played on every single piece of equipment, and seeing it visualized really shows just how wide her range of activity is. Meanwhile, her mother's actions were mainly focused on "watching over" her.

Using a fixed camera, we pressed the shutter about once every 20 seconds, compiling Ito-chan's movements into a single frame.

Professor Ichikawa (hereafter, Professor): This is a really fascinating piece. It's interesting to see how much more active children are compared to adults.

Ishida: Just looking at this makes me feel like children perceive time as much longer. How is that actually?

Professor: Research shows adults and children have significantly different perceptions of time. Psychologically, humans tend to perceive time as longer when experiencing many events. As in these photos, experiencing numerous events in a short time naturally makes the perceived duration longer. Children also feel time more slowly due to physical factors like higher metabolism.

Kutsukake: A higher metabolism makes time feel longer?

Professor: Yes. While not to the same extent as children, adults also perceive time as longer when they exercise and boost their metabolism. Fundamentally, children aren't accustomed to using tools like clocks, so they lack a sense of "how long an hour is." They estimate the length of time based on the number of events that occurred – essentially living by "event time."

Ishida: "Event time," huh! That's true—young children don't even know how to read a clock. Adults might easily overlook that.

Teacher: Exactly. Getting children to act according to a clock isn't as easy as adults think.

Shocking! Telling kids to "hurry up" is pointless!?

Ishida: My child just started elementary school the other day. Even when I say, "We have to leave the house by 8:00! Only 5 minutes left!" they show absolutely no sign of hurrying. At what age do children start to recognize the time on a clock?

Teacher: Generally, developmental psychology suggests that the sense of past and future—like "yesterday/today" and "tomorrow/the day after tomorrow"—develops around age 6. Of course, there are individual differences. It's said that by entering elementary school and getting used to clock-based routines, children finally develop the same sense as adults around ages 9 or 10.

Ishida: Nine to ten years old! So my child still doesn't get it. Actually, I can really feel they don't get it (laughs).

Kutsukake: So, when you say things like "Snack time is later" or "We'll go to the park tomorrow," young children naturally don't understand, right?

Teacher: They might grasp that it's "not now," but they won't know how long to wait. I don't think they really get why it's not okay right now.

Ishida: So they don't understand "Hurry up!" either?

Teacher: They don't understand how much time "hurry up" or "hurry" actually means, so they probably just feel like they're being scolded.

Ishida: So all my "Hurry up! Hurry, hurry!" over the past few years was basically the same as "Hey! Hey, hey!"... That's shocking. I even feel sorry now. So, when you want a child to stop something or hurry up, what should you do?

Teacher: As I mentioned earlier, children judge time by events. So instead of "just a little," clearly state "just once" in terms of number, or use an event as a benchmark like "when this song ends, we're done." When you want them to hurry, give instructions that focus on the task itself, like "Let's race!" or "Who can get dressed faster?"

Ishida: I wish I'd heard this advice five years ago (laughs).

Kutsukake: I'm starting today. Right now.

Comparing the number of "experiences" between children and adults

Ishida: In your book, you wrote, "For adults, a meal is a single event for nutritional intake, but children experience various events even during mealtime (※)." I found this fascinating and decided to observe and visualize mealtime behaviors.

※Source: "Why Is Adult Time So Short?" by Makoto Ichikawa (Shueisha Shinsho)

Kutsukake: These are pie charts showing the actions of my 3-year-old and me, and those of your 7-year-old son and you, Ishida. Beyond eating and talking, they play with yogurt on their hands, cry over spills, sing songs, run around... It really made me realize how many different things they do even just during a single meal.

Ishida: Same here. If I tell them not to play with their food, they sulk and stop eating, or just when I think they're in a better mood, they start dancing...

Teacher: That's interesting (laughs). Kids definitely have far more events. For you two, events include scolding your child or cleaning up spilled food. But when an adult eats alone, there's no "talking," so the graph is just "eating." Then, when you recall it later, the time feels very short. Moreover, the act of "eating" itself becomes a routine event, so the sense of "having experienced it" gradually weakens, and it doesn't even get stored in your memory to begin with.

Ishida: Come to think of it, I can't recall anything about that lunch I ate alone...

Kutsukake: Routine, ordinary events don't stick in our memory. So, conversely, children, who have many first-time experiences, must feel like they're living a considerably longer time than adults.

Teacher: That's right. But spending time with a child having first-time experiences is also a first-time experience for the parent. I think being with their child makes parents feel time is longer too.

Kutsukake: That must be wonderful for parents. I also made a pie chart of a child's day (Sunday). Even this version omits some things, and the sheer number of events was staggering.

Teacher: I see. It's fascinating to visualize just how many events a 7-year-old has in a day.

Kutsukake: It really made me realize again that a 3-year-old spends almost all their time playing, aside from sleeping and eating. Plus, there tended to be more activities in the morning, and the number of events decreased after dinner.

Teacher: That's surprising. You'd expect their metabolism to be higher and bodies more active in the afternoon. But right after waking up, their concentration might not last long, so they could be trying out various play activities. After dinner, children might slow down because bedtime is approaching. In the past, people woke and slept based on sunrise and sunset, so children's rhythms might be closer to that ancient pace than adults'.

Ishida: In modern times, as bedtimes get later and later, children's late bedtimes have become a problem.

Teacher: Physically, it's really not good. Late bedtimes and meal times increase the risk of lifestyle-related diseases.

Ishida: Even for children?

Teacher: Yes. It makes them more prone to lifestyle-related diseases like diabetes and high blood pressure later in life. I think this is something that could be better known.

Ishida: It's surprising that it affects future health. We really need to be careful. If bedtime gets later, wake-up time naturally gets later too. I've also heard that school starts before they can fully concentrate, making it hard to keep up with lessons and leading to lower academic performance.

Teacher: After waking up, it takes about two hours for concentration to really kick in—it's like idling. Your mind starts to feel sharp after about an hour, and if you want to get moving, two hours after waking is ideal.

Playing together is more rewarding for adults than just watching!

Ishida: By the way, even adults sometimes feel time drag on endlessly. Like when accompanying kids at the park. "Are you still playing? Let's go home already," you think.

Teacher: Simply "waiting" while watching someone else act makes time feel longer. Humans tend to focus on the passage of time when they're not doing anything, and the more you focus on it, the longer time drags on. That "waiting" feels incredibly long at the time, but since it doesn't feel fulfilling, when you recall it later, it seems shorter.

Ishida: So it feels long at the time, but when you remember it, it's short? That feels like a loss somehow...

Adults should probably adjust their approach a bit when spending time with children.

Teacher: Fulfilling experiences are remembered as "rich moments" and recalled more easily, so playing together is better than just waiting.

Ishida: Come to think of it, when my child was around three, I used to get frustrated because we'd take so many detours on the way to the park that we'd never seem to get there. But then one day, I suddenly thought, "We're killing time on the roadside. Lucky! I'll try to think that way," and it made things so much easier.

Teacher: You transformed a simple "trip" into an event. Adults tend to think of "play" as starting once we reach the park, but for children, encountering all sorts of things along the way is also "play." That's all part of "going to the park."

Kutsukake: That's so true. By the way, sometimes it's the opposite of stopping to look at things along the way – they'll just keep playing in the sandbox for ages. Do kids have better concentration than adults?

Teacher: When it comes to things they aren't interested in, children's concentration doesn't last as long as adults'. Ten minutes is probably the limit. In this case, they're just focused on one event – playing in the sand – so they probably don't realize how much time has passed. As the sun sets, they'll likely start to feel the passage of time, but if you tell them "It's been an hour already!" during the bright daylight, it probably won't register for them.

Ishida: I see. So the child is just enjoying one activity, yet the parent gets angry for some reason, saying "How long are you going to keep doing that!" From the child's perspective, that must seem unreasonable.

Kutsukake: By the way, Professor, what's a baby's sense of time like?

Professor: We don't fully understand the time perception of children under three. It seems they tend to live more in "event time." Since they lack a sense of present, past, or future, I think they live more immediately in the "now."

Ishida: Since they live in "event time," is it still important to let them experience various things?

Teacher: It doesn't need to be excessive, but taking them out for walks and showing them things is important, also in terms of preparing them for learning.

Online interview with Professor Ichikawa

Adults have experienced much "stolen time"

Ishida: This has become a concern for me. When I'm with my child, I often find myself saying "Hurry up, hurry up," and I started wondering if I'm just impatient. Is being impatient or not something you're born with?

Professor: It's said that lifestyle habits have a greater influence than innate personality. In psychological terms, impatient people are called "Type A." Success experiences where they efficiently used time and succeeded seem to reinforce Type A tendencies. The intense employees of a bygone era are a classic example. They feel even sleeping is a waste, so they get little sleep. They get irritated by perceived inefficiencies, leading to high stress. Because of these factors, Type A individuals are said to be more prone to cardiovascular diseases like heart problems and high blood pressure. People who aren't Type A are often collectively called Type B, and they have a lower risk of these illnesses.

Ishida: So being impatient might be good for work, but it's bad for your health.

Professor: No, when it comes to whether Type A individuals have higher labor productivity, that's not necessarily true in the long run. You can't keep the accelerator pressed down indefinitely. Clocks are tools humans created, but in modern times, humans are being used by those tools. Clocks became so widespread in Japan only after the war. That's just about 75 years in the long history of humanity. Long ago, people used "one kō, two kō" – roughly two-hour units – as a guide for action. Human time perception isn't fundamentally designed for minute-by-minute living. Trying to suddenly adopt minute-by-minute schedules puts physical strain on the body and actually tends to lower team productivity. I don't think the current approach is a sustainable way of working.

Ishida: I see. It makes me reflect on my own work habits, like squeezing meetings into every spare moment. Even when I'm with my kids, I catch myself checking work emails on my phone and get told, "You're always on your phone." I do try to limit how long I look at it...

Professor: People tend to underestimate the time spent looking at their phones or computers. I'm talking about time spent searching or surfing the web. It actually takes quite a bit of time to follow links or type in keywords to find the information you want, but we don't recognize it as an event. Because humans don't properly value that time, it becomes "stolen time." That feeling of realizing two hours have passed while you were just kind of surfing the web is a classic example of "stolen time."

Ishida: "Stolen time." That's scary! I want to be more conscious that the time I spend on my phone is longer than I think, and especially be careful when I'm with my kids.

Kutsukake: One last question: If adults want to simulate a child's experience of time, what should they do?

Teacher: First, perhaps remove all watches and smartphones from your person and try measuring time through experience. Go somewhere like a deserted island resort without a watch or phone and live an extraordinary life. That might be closest to a child's everyday reality.

Ishida: I see! I hadn't thought of that. Immersing yourself in the extraordinary does seem closer to how children experience new things daily. But adults would probably get restless without their phones or watches and take a few days to adjust (laughs).

Teacher: Even for a short time, going somewhere new and spending time without looking at a clock might lead to interesting discoveries.

Kutsukake: I'd love to try that during summer break or something. Wow, everything you said was so valuable—both for the children and for myself. It was incredibly interesting.

Ishida: That's so true. Thank you for sharing such valuable insights.

This time too, there were so many eye-opening lessons.

● Remember, children don't understand clocks. Instead of "just a little" or "hurry up," give actionable instructions like "just once" or "race with Mommy!"

● Time spent just waiting while children play feels long but doesn't become a lasting memory. If you're going to wait, play together instead. Make it a fulfilling, "rich time" that sticks in their memory.

● Children estimate time based on each experience. When they're engrossed in one activity, like playing in the sand, they don't feel much time has passed. It's important to know this.

● People underestimate how long they spend searching on their phones. We stare at screens longer than we realize, so be especially mindful when with children. Adults are chased by schedules, used by time; children live each experience fully. To live better lives, perhaps adults should learn "rich ways to use time" from children. First, I want to create a day free from worrying about time and play with my child until sunset!