Ishida: I see. My child was quite the scaredy-cat, or rather, the type of toddler who wouldn't cross a bridge even if you tapped it, so this makes perfect sense.

Furukubo: So kids who'll eat just about anything are the type with strong novelty curiosity?

Takahashi: That's highly likely. Another factor is genetic elements influencing taste perception. There are three main types of taste bud sensitivity. First, the normal taster, who perceives flavors in a typical way. About 50% of humans are said to be this type. Next, the non-taster, who doesn't perceive flavors as strongly and is completely insensitive to certain bitter compounds. This type, said to make up about 25% of the population, tends to have fewer food preferences. And the third type is the super taster, about 25% of people, who strongly perceive bitterness and spiciness. They are more common among Asian and African ethnic groups and women, and are said to dislike coffee, tea, strongly bitter vegetables, and oils.

Ishida: Three tongue types! I've never heard that before. If a child is a super taster with strong neophobia, they'd likely develop quite a picky eating habit. For such children, how can we gradually increase the variety of foods they'll eat?

If you keep masking the taste of things you dislike, won't you never learn to eat them!?

Takahashi: As I mentioned earlier, human taste is cultivated through experience. So, most people can learn to eat a food if they try it at least 10 times. For example, with bell peppers, regularly let them taste a cooked piece. They might spit it out at first, but eventually, they'll be able to eat it. This is called the "mere exposure effect" in food behavior psychology.

Ishida: Really?! So if I completely mask the taste with other ingredients or seasonings, I'll never be able to eat it?

Takahashi: That's right. People who dislike coffee often try to get used to it by adding milk or sugar, right? That won't make them able to drink black coffee. They'd be better off trying a single sip of black coffee every day, repeating that experience over ten times.

Furukubo: That's surprising. I want to try it, but kids are really good at avoiding things they dislike... so it probably won't be easy.

Ishida: Maybe the key is to sneak in just a little bit at a time, without adding too much.

Takahashi: Forcing them to eat is counterproductive, so be careful there. People born in the Showa era especially were told as kids, "Finish your school lunch!" The culture of "mottainai" (waste not) is important, but we now know that "no leftovers!" actually leads to more foods they can't eat.

Ishida: Whoa, really? Come to think of it, one of our lab members hates natto to this day because their grandmother kept saying, "Eat natto, it's good for your health!" when they were a kid.

Furukubo: But aren't there a lot of toddlers who like natto? My kids eat natto rice all the time. It's smelly and stringy, so why do they like it?

Takahashi: Theoretically, natto is packed with amino acids, which are the source of "umami," so it should taste good. If you eat it before developing an aversion to the fermented smell, you're more likely to like it.

Ishida: I see. So without preconceptions like "this smell is gross" or "stringy things are rotten," natto is essentially a concentrated source of umami. That's fascinating.

"Adults eating it together with relish" cultivates children's taste buds!

Furukubo: Are there other ways to reduce picky eating in children?

Takahashi: Adults enjoying meals together with children. "Shared eating," meaning eating with others, is crucial for developing a rich sense of taste. When adults or friends eat something unfamiliar with obvious enjoyment, it heightens that "curiosity about novelty" we mentioned earlier. It makes children think, "Maybe I should try it too." Fundamentally, the sensation of "delicious" is formed not just by the five senses (taste, smell, touch, sight, hearing), but also by the child's mental and physical state at the time and the local food culture. Memories of people around them eating with relish or of enjoyable mealtimes are crucial elements in shaping what tastes good.

Ishida: I see. When my kids were little, I was so focused on getting them to eat that I'd end up shoveling my own food down standing up after they finished. That definitely doesn't make you want to try new dishes, does it? I regret that.

Furukubo: Maybe it's okay to just relax, focus on the dishes you want to eat yourself, and then share some with your child.

Takahashi: Exactly. Also, talk about the flavors constantly. Say things like, "This is crispy and delicious," or "The umami spreads in your mouth." The more adults discuss taste, texture, and other aspects of deliciousness, the more a child's vocabulary about food will grow.

Furukubo: So expressing it in words is important?

Takahashi: Without words to express it, you can't describe it. It also makes recognizing that specific taste or texture harder. For example, it's said that ethnic groups without the word "astringency" describe everything, including astringency, as "bitterness." In that sense, having more words to express things means your sense of taste becomes richer.

Ishida: I've heard the saying that countries without the word "stiff shoulders" don't experience stiff shoulders. It exists, but it becomes as if it doesn't. It's the same thing!

Takahashi: Also, avoid making assumptions like "Kids probably can't eat this" or "They probably won't like it." I'll say it again: don't force them to eat leftovers.

Ishida: A nursery school teacher mentioned that for children who eat little, they serve smaller portions from the start to give them a sense of accomplishment—"I finished it all," "I had seconds." That way, they don't leave anything behind. Also, it seems like "eating alone" is more common now than in the past. Kids often eat hurriedly by themselves between lessons or cram school, right? Even if every meal is difficult, I want to increase the "time enjoyed together over meals" with my child as much as possible.

Takahashi: By the way, I prepared an experience that might be close to "how a child feels when trying something new." Would you like to try it?

Ishida: Actually, I've been curious about that ingredient right there (laughs). Please, let's do it!

It tastes different than I expected! I finally understood that feeling of spitting it out.

Takahashi: We're going to do an experiment to taste something unexpected by blanking out your senses. Please hold this Gymnema Sylvestre tea in your mouth for about 30 seconds before swallowing.

Ishida: It's... bitter, this tea.

Takahashi: Now, please try the sugar, chocolate, roll cake, and mandarin orange I've prepared here. Also, the cola and beer.

Ishida: Huh? Hmm??? The sugar tastes like chewing sand, and the chocolate feels like eating clay. The cream in the roll cake... like... paint? What is this?!

Takahashi: Gymnema Sylvestre tea has the effect of blocking the perception of sweetness. Without tasting sweetness, none of it tastes good at all, right?

Ishida: The mandarin tastes sour like a lemon, and the cola and beer are just sour-bitter juice! Yuck! This... This... I think I finally understand that feeling kids get when they taste something totally different from what they expected and spit it out. Yikes.

Lab members experiencing "It tastes different than I expected!"

Ishida: This was an incredible experience. Super interesting. And I learned so much. Thank you, Takahashi-san!

An experience that makes you feel like a child trying something new

We tried making "What's this? Lunch"

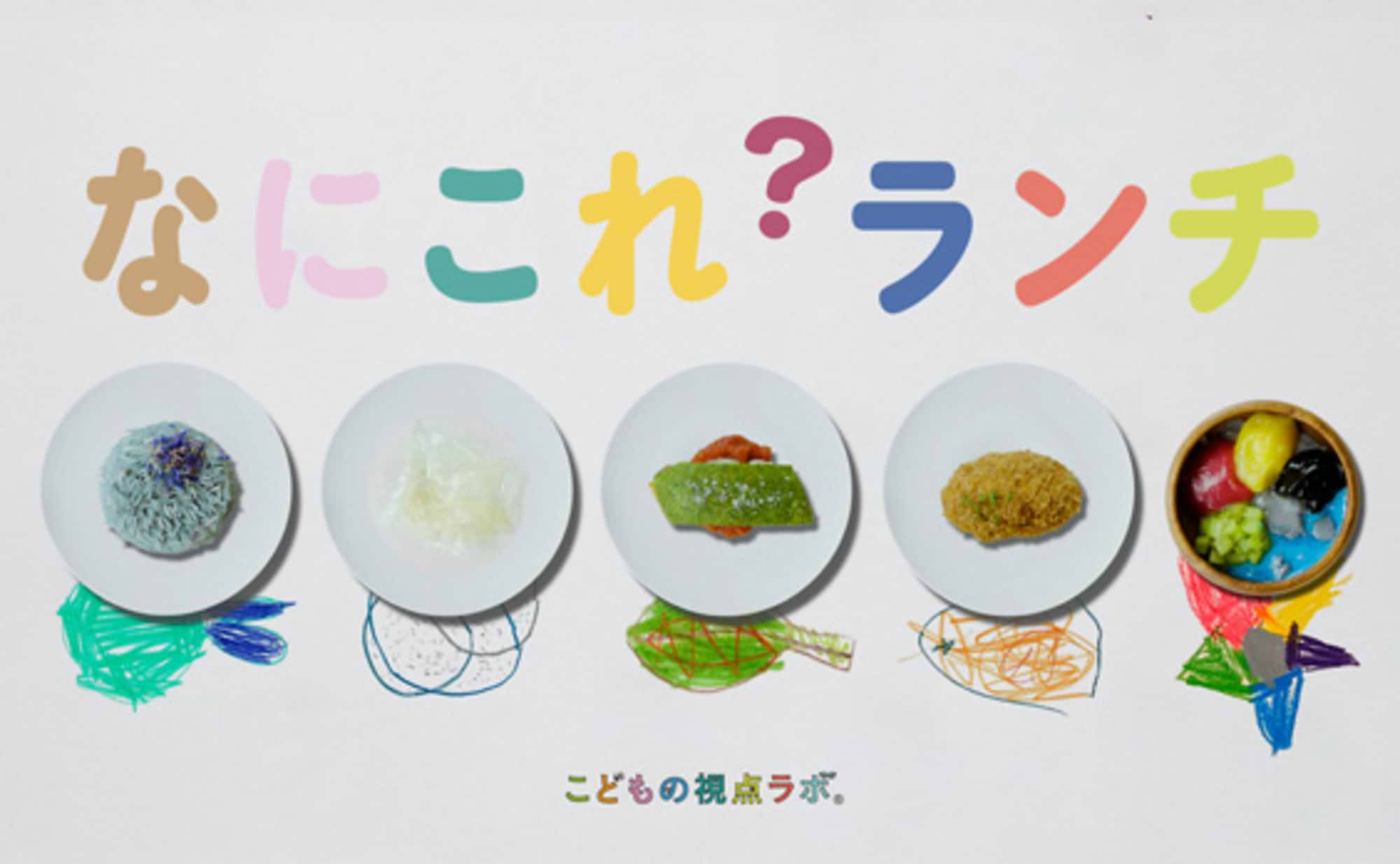

At the Taste and Aroma Strategy Lab, we experienced that feeling of "I was looking forward to it, but it wasn't tasty at all!" Using that as a reference, the Children's Perspective Lab wondered: Could we create a menu that, amidst the tug-of-war between "novelty aversion" and "novelty curiosity," makes kids think "It's new, but it was delicious!"? We named it "What's This? Lunch."

First, we asked children visiting the "ITOCHU SDGs STUDIO Children's Perspective Cafe" to freely draw pictures representing taste sensations. They chose from six categories: "delicious (umami)", "sweet", "salty", "spicy", "sour", and "bitter". We collected taste image drawings from 192 children, primarily aged 1 to 10. The results were truly fascinating!

Adults might tend to depict "sweet" as something pink and fluffy, but the children drew it blue, green, or even spiky. "Sour" was sometimes square or red. The variety was truly remarkable.

192 children drew diverse "flavor images"

We picked six particularly surprising examples of "This taste is this color or shape!" and decided to create dishes based on those drawings. We collaborated on menu development with Crazy Kitchen, who designs custom "food" experiences—time and space dedicated to enjoying food.

You couldn't tell what they tasted like just by looking. But when you tried them, they were all wonderfully delicious lunch plates expressing "umami (savory)", "sweet", "salty", "spicy", "sour", and "bitter".

This menu was specially prepared and served at cocon, a Tokyo restaurant in Nakameguro renowned for its innovative European cuisine, by its owner-chef, Masatomo Kuribuchi! We invited families with young children: the Takahashi family from the Taste and Aroma Strategy Laboratory, whom we spoke with at the beginning, and the Mada family.

Now, which dish represents which flavor? They ate while trying to guess the six flavors. When the lunch plates were served, both families gasped in surprise. In the photo below, from left to right, you can see blue rice made with butterfly pea, a leguminous plant; transparent chips made with agar; grilled green herbs (?); something resembling a minced cutlet; six small bowls of vividly colored dishes; and something covered in black sauce. Although the dishes look colorful, they are all made with natural ingredients.

"Delicious (umami)," "sweet," "salty," "spicy," "sour," "bitter."

Now, try to guess which flavor is which.

"The rice is... blue." "What is this black sauce? I can't imagine what it tastes like at all."

The adults seem a bit confused. In fact, the kids seem to be eating without hesitation. Maybe it's because they don't have preconceived notions.

*The "spicy" version for adults uses chili peppers. The children's version does not.

"Isn't this spicy? Huh? It's bitter!" "I thought this would be salty... but wait, it's sweet!?" "This is spicy! Oh, but I kinda like it." "I didn't expect something this color to be sour." "Hmm... my brain is confused!" "Ah, this one has incredible umami."

A lively, fun lunchtime filled with chatter. Afterward, we asked everyone for their impressions.

"I ate with my heart pounding. Since kids probably haven't tried most of these things before, it made me realize that every day must be like this for them."

"It really made me think about children's fears. Eating something you've never tried before—this is what that feeling must be like."

"When I first saw it, I thought, 'Wait, is this even edible?' (laughs). It made me realize we need to help kids understand that it's okay to eat it."

"Things you've never seen before are hard to eat. I thought maybe I could try making things look more appealing to kids first."

We lab members actually had this lunch too. We felt the fear and excitement of eating something unfamiliar, and the joy when it tasted good – it was a strangely rich food experience. So, here's what we learned this time, summarized.

● Even in the womb, fetuses sense the flavors of foods their mothers eat through the amniotic fluid, learning about "safe foods" and preferences.

● For toddlers, who are trying almost everything for the first time, "novelty fear" and "novelty curiosity" battle in their minds. Know that children where fear wins won't eat something right away.

● Rather than masking the taste of disliked foods with seasonings, eating even a tiny piece of that taste over 10 times or more makes it more likely they'll eventually accept it. However, forcing them to eat is counterproductive and can increase the number of foods they refuse, so caution is needed.

● "Deliciousness" isn't just about the five senses; it's shaped by local food culture and memories of enjoying meals together with others. Rather than having children eat balanced meals alone, adults sharing and enjoying those meals together helps cultivate a richer sense of taste. Incidentally, my child, who was an incredibly picky eater as a toddler, is now 10 years old. Over the past few years, their range of acceptable foods has expanded significantly, and they've started to truly enjoy eating. A child's picky eating habits won't change overnight. Precisely because of this, I've come to believe that instead of demanding "Eat this!", it's better to enjoy the meal together, saying things like "This is delicious!" while sitting at the table. This approach keeps the adults smiling too (and eventually, the child's range of acceptable foods expands) – it's nothing but positive!