We decided to investigate "how children see," but we couldn't exactly interview babies asking, "What do you see?"... So we spoke online with Professor Keizo Shinomori of Kochi University of Technology, who researches human vision.

Furuichi: Professor, right off the bat, I've heard that "babies' eyes only see things blurrily." Is that actually true?

Professor Shinomori (Professor): Yes, immediately after birth, they see almost nothing. Their visual acuity is around 0.001. By about 3 months old, it reaches around 0.1. Between 8 months and 1.5 years old, it reaches around 0.3. It's thought that they achieve visual acuity of around 1.0 by around age 3. Of course, there are individual differences.

Furuoi: Vision doesn't reach 1.0 until age 3! I thought they could see almost as well as adults by around age 1.

Teacher: At one year old, they still don't see colors the same way adults do. Beyond that, the degree of blurriness, depth perception, and sense of distance also differ from the world adults see. There are also differences in visual field narrowness and stereoscopic vision , but they likely start seeing colors nearly equivalent to adults around age six.

Furuoi: I see. So even though we simply say "seeing," it involves many complexly intertwined elements.

Cooperation: Professor Keizo Shinomori, Kochi University of Technology Production: Children's Perspective Lab

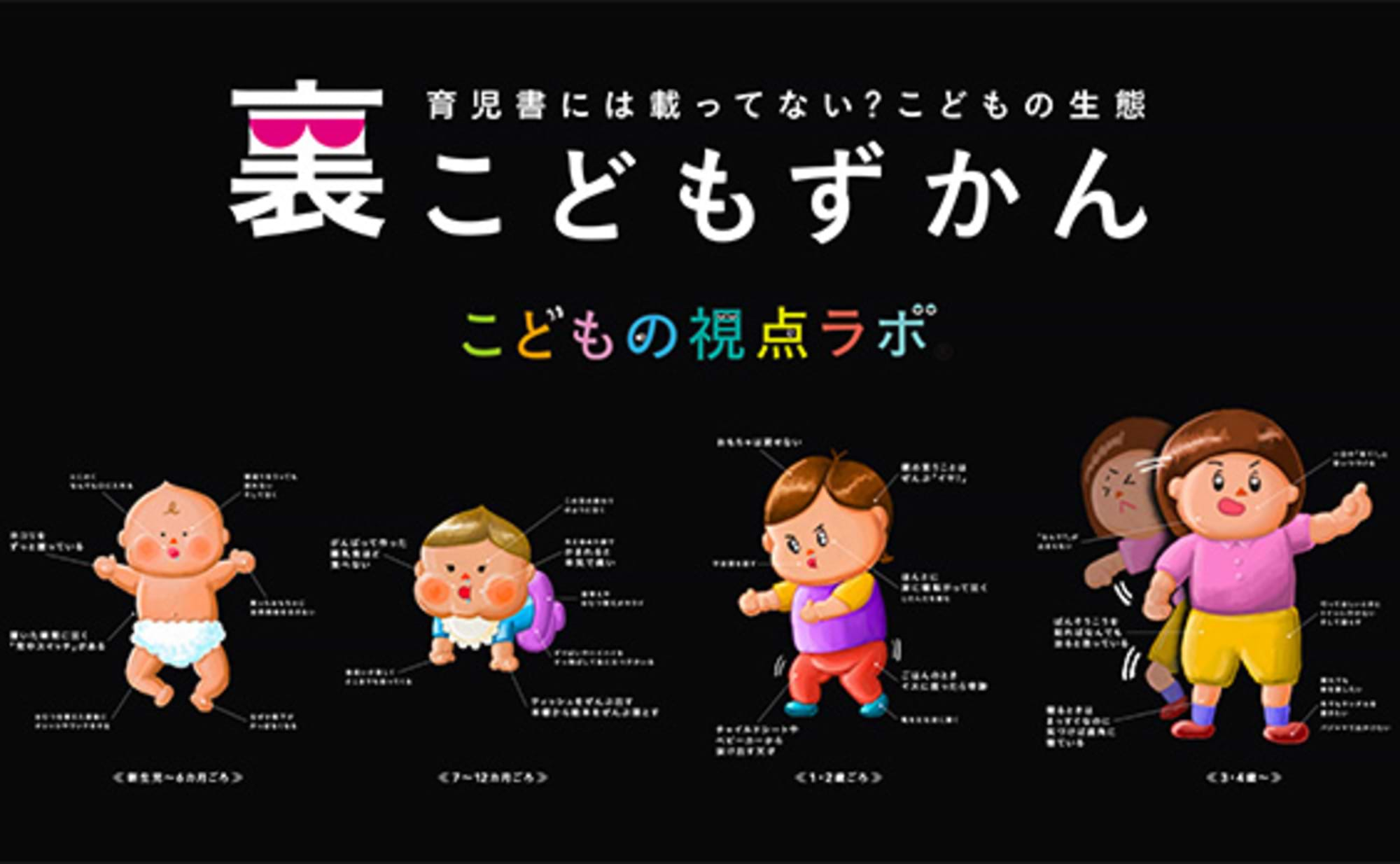

Furuoi: Here is the "Child Vision Chart" we created with the professor to recreate how children see at each age.

My honest reaction was, "I thought they could see more than this." Furthermore, since I have perfect vision (1.0 or better) without glasses, it was hard for me to even imagine what it feels like to have "difficulty seeing"...

So, with Professor Shinomori's cooperation, we developed an app that lets you experience "child vision" by age, and lab members tried it out.

And what's more!! The scenes viewed through the app were recreations of a "child's room," made possible with the cooperation of IKEA! It turned into a truly special research project.

On the day of the research, we recreated the children's room together with the IKEA team.

Furuoi: What were the reactions of the IKEA team members as they peered into the children's room through the tablet screen with the app installed?!

"Wow! Is that how it looks?!" "Huh, so you can see through red?!" Everyone seemed to have their own surprises and interesting discoveries.

IKEA staff and lab members peering at the tablet

Furuichi: Later, we showed the footage to the professor and delved into the truth about how children see.

Room set cooperation: IKEA Japan Co., Ltd.

Teacher: Wow! What a colorful and fun children's room!

Furuichi: Isn't it wonderful? I almost wanted to live in this room myself (laughs).

Teacher: And it's great that everything in this room is scaled for children. Furniture and items made for adult sizes are too big, making it hard for kids to grasp the sense of scale.

Furuichi: I see! That's truly the "child's perspective"! Now, let's try experiencing "how a newborn sees the world at two weeks old."

Furuoi: It's... dark. And with the added blur, it's a completely different world from what adults see.

Teacher: Newborns can only vaguely recognize shades of white, black, and gray.

Furuoi: Really? Actually, when my own child was just born, I had this touching moment thinking, "They can see Mom's face!" Was that just a parent's delusion?

Teacher: It wasn't a misunderstanding. Babies start preferring to look at their mom after just 12 hours of life, and it's said they can recognize her face within 3 or 4 days. However, they can't see fine details yet. It's thought they recognize her not by facial features, but by the boundary between the outside world and their mom—the areas with clear contrast.

Furuoi: What do you mean by that?

Teacher: As you can see from the visual image in the "Child's Visual Perception Chart," Mom's hairstyle appears relatively distinct compared to other features, right? The baby is judging based on Mom's hairstyle.

Ozaki: Interesting! Does the baby see the father the same way?

Teacher: Unfortunately, it seems to be more like "Mom + others." A more accurate description might be "the person who provided the most care initially + others." Only when someone consistently cares for the baby from the front and consistently shows their face directly will the baby recognize them. If someone only appears from the side while caring for the baby, it seems the baby won't recognize them.

Also, babies can't recognize profiles until around 4-5 months old. So even if it's Mom, if she's interacting while looking at her phone or TV and only showing her profile, the baby might not recognize her. It's important to talk while looking directly into the person's eyes from the front.

Furuoi: So they vaguely recognize people who are absolutely essential for their survival, huh?

The world babies see is within a 30cm radius!?

Furuoi: Next, let's look at how they see things at "3 months old." They can see colors like red and green, albeit faintly. But it still seems like everything is blurry.

Doctor: What babies are trying to see is within their reach—the world within a 30cm radius. They can see things close by like stuffed animals or bottles, and if Mom enters that space, they see Mom. By looking at and touching these things, they work hard to connect the visual information with the actual size they feel, learning as they go.

Furuai: I see! The idea of their immediate reach makes perfect sense.

Ozaki: That's fascinating! What about perspective?

Teacher: This isn't about children, but there's an interesting study on perspective from a certain tribe. They took members of this tribe, who live deep in the jungle and have never seen long distances, out to the savanna. They showed them a giraffe far away and asked them to estimate its size. What do you think they said?

Ozaki & Furuichi: Hmm...

Teacher: They reportedly answered, "About the size of a small animal." We, who know that "far away = appears small," understand that even if the giraffe appears small on the retina, distant objects appear small. So we can imagine the giraffe is a large creature. But people who have only seen nearby objects cannot make that calculation; they perceive the size on the retina as the actual size. Seeing the giraffe, they recognize it as a very small creature.

The earlier example of the baby's 30cm radius is similar. It's said that initially, children can only recognize the actual size of things within their reach. By seeing and learning about various objects, they gradually acquire a sense of three-dimensionality and perspective.

Furuoi: That's incredibly fascinating! Indeed, even if someone looks like a grain of rice from the top of a building, our minds instantly convert that perceived size to the actual size. Our experience of seeing the real thing countless times before surely plays a role in that.

Adults instantly process what they see in their minds

Furuoi: Finally, the "3-year-old's" perception. At this stage, it looks almost indistinguishable from an adult's.

Teacher: While their perception of color is quite close to an adult's, there is one major difference.

Ozaki: What is it?

Teacher: Their field of vision. Children have a narrower field of vision. While an adult's field of vision is said to be approximately 150° horizontally and 120° vertically, even a 6-year-old is said to have only about 90° horizontally and 70° vertically. Younger children see even less than that.

※Source: Tokyo Children's Safety Project Column "vol.005: Accident Prevention Tailored to Child Development? Introducing Age-Specific Accident Trends and Experiential Tools to Understand Children"

Ozaki: I see. I often find myself yelling "Danger! Red light!!" when walking with my child, but if they can't even see the traffic light, there's no way for them to be careful, right?

Teacher:Children not only have a narrower field of vision, but they also lack the awareness that they need to be careful when walking. They just look at what they want to see; if Mom is right in front of them, they'll run straight toward her. It's also hard for them to divide their attention. If they focus on avoiding a hole in the ground, they might bump their head because their attention is concentrated there. Their focus tends to be very narrow.

Furuoi: I often warned my child, "Danger! Look, a car's coming! Pay attention!!"

Teacher: When crossing a crosswalk while watching for cars, adults instantly calculate whether it's safe to cross. They factor in the actual size of the car, its approaching speed, and even their own walking speed. Expecting children, with their narrow field of vision and still-developing brains, to perform this complex simulation is difficult.

Furuoi: Honestly, just hearing that makes my head feel like it might explode.

Smartphones and TV: The Hidden Dangers of Passive "Viewing"

Ozaki: Changing the subject, there's something I've been wondering about. When we really want kids to be quiet, we tend to give them smartphones or tablets to watch. What kind of impact does this have on their eyes?

Teacher: I don't think watching videos for about 10 minutes has a major impact on their vision. However, psychologically, there's the question of whether they can actually stop after just 10 minutes. Humans tend to constantly seek new, strong stimuli. If they keep watching videos nonstop, I worry whether they'll ever be able to go back to picture books...

Ozaki: It seems like a situation where you temporarily let them watch videos on your phone, but then they lose interest in everything else, leaving you stuck later...

Teacher: Another issue is that smartphones have a small viewing angle and lack impact, so children want to get closer to the screen. As a result, if they keep watching from a close distance like 20cm, it creates a disconnect with the real world.

Ozaki: What kind of contradictions arise?

Teacher: When viewing things in real life, we naturally judge distances correctly. We squint to focus on nearby objects and look straight ahead for distant ones. With smartphones or TVs, the distance from your eyes to the screen is fixed, so you're constantly squinting to focus on something close. This differs from how we move our eyes and adjust focus when looking at distant or nearby objects in the real world. Consequently, prolonged screen viewing can cause discomfort and fatigue.

Ozaki: I see.

Professor: Furthermore, video information is limited and can only be viewed "passively." Watching footage of animals on the savanna doesn't allow you to perceive depth or distance. Visiting a zoo lets you see life-sized animals. Moreover, they appear larger when you approach and smaller when you move away. The fact that your perception changes as you move is extremely important for visual development.

Ozaki: Regarding eyesight, I recall reading an article about overseas research suggesting that longer exposure to ultraviolet light may help prevent vision deterioration. Is that actually the case?

Professor:Exposure to violet light, a specific wavelength within sunlight, is thought to suppress excessive eyeball growth, making it harder for myopia to progress. I've heard that Taiwanese elementary schools have rules like "no staying indoors during recess," and statistically, fewer children are becoming nearsighted.

Additionally, playing outdoors naturally encourages looking at distant objects rather than close-up devices like smartphones or tablets, which is also thought to be beneficial.

Seeing and experiencing real objects improves accuracy

Ozaki: From a visual perspective, is there anything you'd like to convey to today's children and the adults around them?

Teacher: "Experience" is crucial. It's better to show children "real objects" before they enter elementary school. For example, at the zoo, they can experience smells and sounds while observing movement—and sometimes even an animal's lack of motivation (laughs). This "active" visual information gained by walking and looking is extremely important for development.

At experiential facilities like zoos, children can choose whether to look or not, glance briefly, or observe intently—all based on their own interest and will.

Ozaki: Is there meaning in visiting places like zoos even during infancy, when they likely see very little?

Professor: Children accumulate visual experiences by persistently looking at various things, thereby refining their visual acuity. Even babies who can barely manage to roll over possess the ability to choose what to look at or not. Looking to the right reveals the scenery on the right. Looking to the left reveals the scenery on the left. This is entirely different from an environment where images pass by in one direction for a short time.

Deciding what to look at or ignore based on their own interests and curiosity is thought to be extremely important for the development of the cerebrum. Even if the child doesn't remember it, I believe it has an effect on visual and brain development.

Furuoi: For example, when a child sees snow for the first time, do adult comments like "It's so fluffy!" or "The snow is pure white!" influence visual development?

Professor: In early cognition, it probably doesn't have a huge impact at that stage. However, talking to them helps them learn to extract meaning from ambiguous things. They naturally learn to see "color," but they won't understand what specific "color" it is unless you tell them. Speaking to them using rich language is very meaningful in terms of imparting background knowledge about what they see.

Furuoi: It's good to know my actions—talking endlessly to my unresponsive son in the cold—had meaning (laughs).

These episodes about "how things are seen" were blind spots for me as an adult. Learning about how children perceive things gave me a chance to rethink how I talk to and interact with them. Thank you, Professor, for such an interesting talk! Now, here's a summary of what we covered.

● Newborns have visual acuity of about 0.001. It's thought they reach about 0.1 around 3 months, about 0.3 between 8 months and 1.5 years, and achieve adult-like 1.0 vision around age 3.

● Babies can recognize "the person who cared for them the most initially" by 3-4 days old. They recognize faces from the front most easily, so it's important to look at the baby's face and eyes while caring for them.

● While vision reaches nearly adult levels around age 6, the field of vision remains significantly narrower than an adult's. Parents often say, "Look closely!" but should be aware the object might not even be within the baby's field of vision.

● Actively viewing real objects involves choosing what to look at based on interest—a behavior crucial not only for vision but also for brain development. Show babies plenty of "real" things, not screens, from infancy.