Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

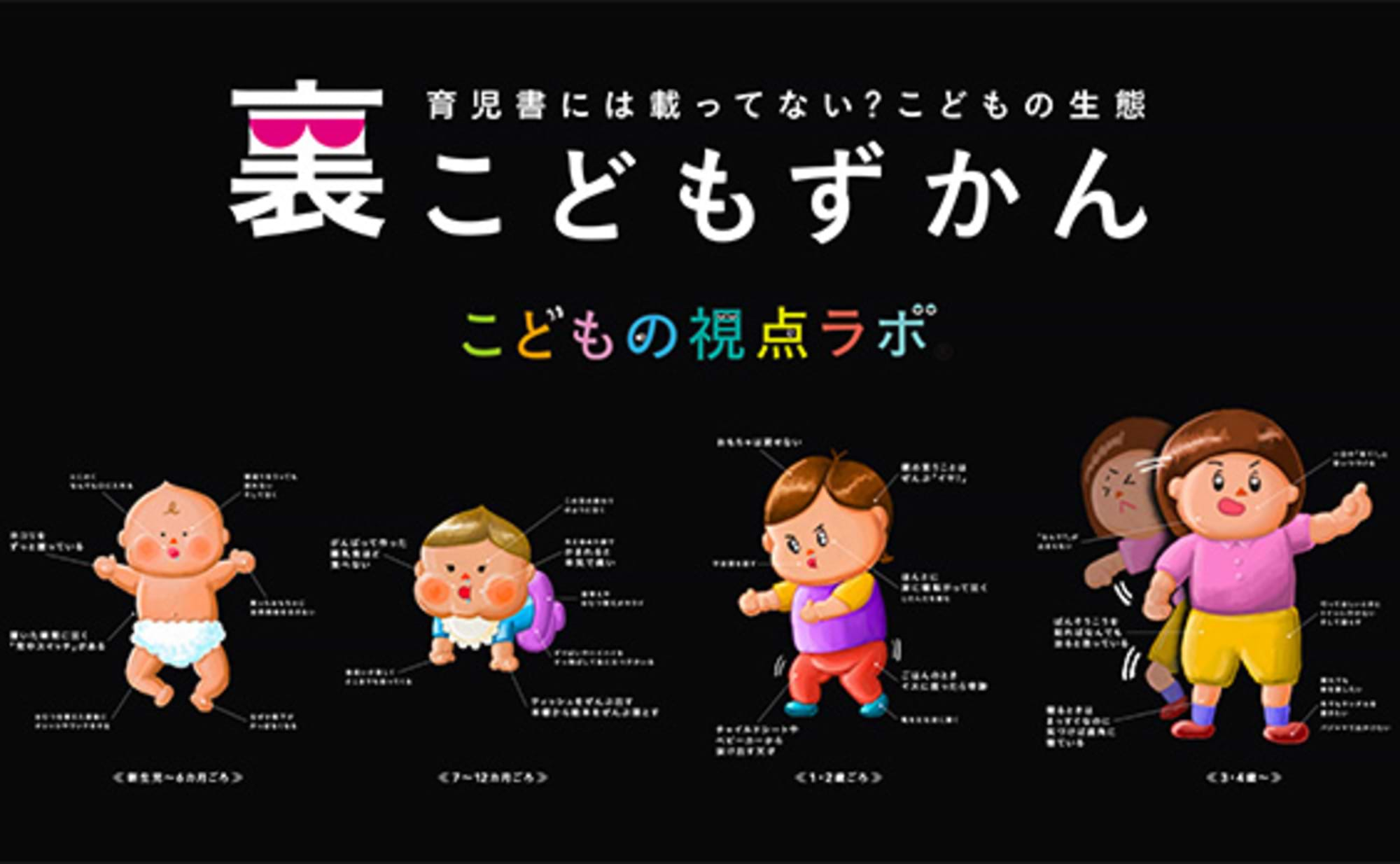

【Child's Perspective Lab】Not in parenting books? Parents' collection of hidden child behaviors: "The Hidden Child Encyclopedia".

The Children's Perspective Lab, where we see the world through a child's eyes. This time, we're changing things up a bit and collecting examples of children's "hidden" behaviors that parents think, "I didn't know that!" or "I never heard about that!" even after studying parenting books. The main members for this research are Makiko Umeda and Hitomi Sato, both moms of two girls.

Sato: My younger daughter started walking early, skipping crawling altogether and beginning to walk before she was even one year old. While part of me thought, "Wow! My kid must have great motor skills!", the other part worried because her crawling period was so short...

Searching online for "not crawling at 1 year old" or "short crawling period" only brought up average crawling start times and generic developmental calendars. Back then, I worried and fretted, trying not to care but actually caring a ton.

Umeda: Even within our lab, many shared worries about comparing their child's development to growth charts, like "I panicked when she didn't roll over at all during that stage" or "I searched endlessly in the middle of the night." We also heard lots of "parenting realities" like: "I never heard newborns poop so many times a day!", "I was shocked by Niagara Falls-level drool!", and "Throwing food?! I was stunned (but got used to it eventually)". These made us think we might have had a bit more peace of mind if we'd known about them before having kids.

"It wasn't just my kid!" The behavior patterns of Lab members' children, totaling 21 kids.

Currently, there are 15 lab members. Their children range in age from 0 to 10 years old, totaling 21 kids! We gathered unexpected words and actions discovered by each parent during their childcare journey. We compiled the most relatable ones—those that elicited responses like "I get it!" or "That happened at our house too!"—into an illustrated guide format.

We'd like to explore this chart together with Professor Yoko Okamoto from Rissho University, who also contributed to Children's Perspective Lab Report No. 5.

Sato: Professor, thank you for joining us. In creating this "Secret Children's Picture Book," we also referenced the "Concerns Map" (a map compiling various "concerns" felt during child-rearing) you participated in. First, let's look at newborns to 6 months old.

Umeda: Frankly, what are your initial impressions?

Professor Okamoto (hereafter, Professor): It's very interesting. I found myself laughing while looking at each one.

Sato: I incorporated something Professor Okamoto taught me before into "Crying Just Because It's Boring." Was there anything else you particularly resonated with?

Professor: "Not showing any interest in a toy they bought" is something I think many moms and dads have experienced. Of course, there are individual differences.

Sato: My child was the same way—even if I bought them a cute toy, they preferred everyday things like plastic bottles or remote controls lying around.

Teacher: You need to be careful they don't swallow caps or batteries, but babies at this stage are in the phase of putting everything in their mouths to explore. Speaking of putting things in their mouths, thumb-sucking also starts around 2-3 months. After about 6 months, they start sucking their feet. Babies' bodies are soft, but initially their abdominal muscles are weak, so they can't lift their legs. Around six months, when they start learning to sit up, their abdominal muscles develop enough to lift their legs, and that's when they start sucking their feet.

Sato: Do babies recognize their own feet?

Teacher: Exactly, it becomes the trigger for recognition. Actually, when babies are born, they don't know their own boundaries. At first, they don't know where they end and others begin, and they can't control their own bodies well. But when they suck their fingers, they simultaneously feel the mouth sucking and the hand being sucked. That's when they discover, "Ah, this is me!" Conversely, when they touch someone else, they feel the act of touching but not the sensation of being touched. That's when the baby realizes, "This isn't me, it's someone else."

Umeda: That's fascinating! There's also something called "hand regard," where babies discover their own hands. Seeing a baby gaze curiously at their own fist is both amusing and adorable—really memorable.

Professor: You wonder, "What's so rare that they're staring so intently?" But actually, most babies aren't just watching—they're moving their hands at the same time. By combining the sensation of moving their hand with the visual information, they realize, "Ah, if I send a signal from my brain, I can move my hand."

Umeda: So by repeating the cycle of sucking their thumb, watching their hand, then sucking their thumb again, they go through the process of realizing, "Ah, it really is me!"

Teacher: Exactly. Babies who couldn't see their feet clearly before, and never even thought about what was happening below their belly button, start lifting their legs and putting them in their mouths around 6 months. And they make this huge discovery: "I extend all the way to the edge of the world!"

Sato: Thinking about it that way, just sucking on their feet is precious. As parents, we end up saying, "Stop it~ Don't put your feet in your mouth~" (laughs).

Are Japanese babies bad at crawling? Differences in environment compared to the West.

Umeda: Next, let's look at the period from around 7 to 12 months.

Sato: This is something I personally worried about—is it common for some babies to "skip crawling and suddenly start standing"?

Teacher: Yes, quite a few do. I feel that compared to babies in Western countries, many Japanese babies aren't very good at crawling.

Sato: Huh? Not good at crawling?

Teacher: I think it's because Japanese homes are often smaller compared to Western ones. There are things like small bookshelves or low tables right nearby, creating an environment where it's easy for them to pull themselves up. They get used to pulling up early and then start walking without crawling at all—that's something we see quite often.

Umeda: It's true, homes in Western countries are spacious. If there's distance to cover, babies get more chances to crawl, but if they reach their destination quickly, they might think, "Well, I don't really need to bother crawling..."

Teacher: Exactly. Since they have fewer chances to move long distances, Japanese children aren't as eager to crawl. Instead, you often see them doing the sliding crawl, high crawl, or one-sided high crawl. The sliding crawl is where they move along without putting their stomach down, staying in a seated position the whole time. High crawling is crawling where the child doesn't put their knees down, but instead lifts their bottom up with their toes. One-sided crawling, as the name suggests, is crawling where the child moves with one foot on the floor and the other knee on the floor. My impression is that many children do one-sided crawling.

Sato: Hearing you talk about it now is the first time I've learned the names, but my child was definitely a one-sided high crawl!

Teacher: Babies who do one-sided crawling will try hard to move toward Mom or Dad when called, but because their left and right legs aren't balanced, they often end up turning sideways. Then, they notice they're sideways midway, turn back toward their parent, and crawl hard toward them, only to repeat the same thing. But it's kind of efficient, you know? They can move faster than babies crawling with both knees on the floor.

Sato: Yeah, they definitely moved fast (laughs). Also, my friend's kid was a crawling type.

Teacher: You know how babies often seem quite content sitting in a space surrounded by cushions? In Japan, they can just sit in that enclosed spot and reach out their hands to grab whatever they want. Even if they can't quite reach, they can slide their bottom forward a bit and get their hands on it – "Yes, mission accomplished!" Maybe those kids choose to crawl like that. The ones who crawl on their hands and knees seem to find the posture uncomfortable, so they often start using their knees more and more.

Sato: Babies might be optimizing their crawling to suit their environment and mood. Back then, mine hardly crawled at all, and when he did, it was a bit different from other kids, so I was worried... Thanks to Dr. Okamoto, I feel so relieved.

Sibling fights happen because one-year-olds lack the "concept of ownership," while four-year-olds have the "concept of prior ownership."

Umeda: Next is around age 1 or 2. The 1-year-old's "I won't share my toy" was also a behavior that resonated strongly within the lab. Kids stubbornly resist when someone tries to take something they're playing with, right?

Teacher: Children's "I don't want it taken because it's mine" is called the "concept of ownership" in technical terms. But actually, at age one, they don't possess this "concept of ownership." Since they don't have the idea of "mine," they also can't understand the rule of "lending or not lending."

Sato: I imagined it as them saying, "I don't want to share this toy because it's mine!" Is that a bit off?

Teacher: That's right. It's closer to "I don't want to share because I'm playing with it now" rather than "because it's mine." Even if they were engrossed in playing with a toy, if they later pick up something else, they won't mind if it gets taken away.

For example, one-year-olds love long, thin things like pens and grab them right away. But if you try to take it away, they clench their fist around it. The more desperate you get, thinking "This is dangerous!", the more they seem to hate the very act of having it taken away. That's when you show them something else, like "Look, I have this over here~". They grab the new thing, and suddenly their attention shifts away from the pen. They're still at an age where you can distract them.

Umeda: That's similar to what we discussed earlier about "getting distracted and forgetting what they were doing." When they won't share a toy, it's not because they think it's theirs. It's not about how long they've been holding it. They just hold onto it because they have it, without any particular attachment.

Teacher: Exactly, they're not greedy at all. But they treat other people's things the same way. If something is there, they'll touch it, which is how sibling fights start. Older kids have a developed sense of ownership, so they'll say, "I put it here because I wanted to use it, why did you take it?!" But a one-year-old thinks, "No, whatever's there belongs to everyone, right?"

Around age four, the concept of "first touch ownership" emerges—the idea that whoever touches something first gets it. The notion that actively touching something makes it yours gradually develops , leading to fights with younger siblings. Some call this the "active touching theory."

Umeda: So even saying "I can't share my toy" has a different meaning depending on the age, huh.

Teacher: At 2-3 years old, kids often say things like "Here you go!" or "Okay!" and automatically hand over toys, right? Those are like magic words—often the child doesn't truly understand the meaning and ends up thinking, "Oh, I gave it away. Why did I do that? What should I do?" Even if they seem to lend it on the surface, the actual concept of lending isn't fully formed.

Sato: At support centers, I often saw scenes where a child was using a toy, another child looked like they wanted it, and the mother would say, "You've played with it long enough, share it. It belongs to everyone," leading the child to burst into tears. Some parents then worry, "Why is my child so selfish? Did I say it wrong?"

Teacher: "Can't share toys" sounds negative, but in a way, it's a sign of development. Think about it – isn't it amazing they understand "my things"? They're interested in that toy, distinguishing between their own possessions and someone else's. And they can express their feelings clearly. I want to tell parents, "It's perfectly normal they can't share yet," so they shouldn't worry.

Kids' "Why? Why?" isn't about wanting the right answer!?

Umeda: Next up is the "hidden" behavior of children aged 3 and older.

Umeda: Around this age, the "Why? Why?" barrage just doesn't stop, does it?

Teacher: Exactly. Around age 4, they start asking "Why is it like this? Why is it that?" But even when parents try hard to answer, they're not really listening. They bombard you with questions, yet when parents seriously engage and explain, don't they just look completely disinterested?

Sato: Exactly! What should we do in those moments?

Teacher: I think the right answer is to laugh and say, "Oh, you weren't listening, were you? Ha ha!" Of course, answering in your own words is important. But kids don't just want the right answer; they actually want to interact with their parents. That's why they ask the same thing over and over.

Sato: So they're not really trying to figure out the reason?

Teacher: Exactly. At first , they're less interested in figuring out the reason and more in just knowing if there is one. Beyond that, they just want to interact with Mom or Dad. That's also why they babble meaningless words around age one. But if parents get desperate trying to understand them—"Is it that? Is it this? Which one? What do you want?"—the child will just dismiss them with "No!"

Umeda: So from the child's perspective, they were eager to interact, but getting a long explanation just made it less fun. Yet parents start getting annoyed, thinking, "You asked the questions, so listen properly!"... That's really heartbreaking when you think about it.

Professor: The "Why? Why?" phase at age 4 is roughly the counterpart to the "This is this?" phase at age 2. Two-year-olds want to know the names of things, so when you go for a walk, they ask "This is?" so much you can't move forward. Even when reading picture books, the story itself doesn't really matter yet—it's all "This is?"

Sato: It's so cute to think that both "What's this?" and "Why, why?" come from wanting to talk with their parents.

Teacher: Exactly. So even if they get a "No!" in response, moms and dads absolutely don't need to worry that "my explanation was bad..." Just enjoy interacting with your child right in front of you.

Sato: My child has recently started the "Why? Why?" phase, so I want to approach it with that kind of relaxed attitude.

Umeda: Teacher, thank you so much for all these stories that shed light on the hidden side of children! Now, let's summarize this session.

●Even if you study parenting books in advance, children worry or frustrate adults with their individual growth differences and unexpected behaviors. Actually, many moms and dads have similar experiences, so don't panic thinking "Is it just my child?"

●There's a reason behind children's challenging behaviors. For example, babies suck their fingers or toes to understand the boundary between themselves and the world. Repeatedly asking "Why?" is their way of wanting to interact with their parents. Understanding this background might help you see troublesome behaviors in a different light.

●  ;Behaviors that worry parents can actually be specific to the environment or signs of development. For example, "not crawling" isn't uncommon in Japanese living environments, and "not sharing toys" is part of developing the concept of ownership. So, there's no need to worry excessively. This time, just among the lab members' children, we found plenty of "It wasn't just my kid!" moments. To further enhance the content, we are currently exhibiting and collecting submissions for the "Secret Kids' Encyclopedia" at the "ITOCHU SDGs STUDIO Children's Perspective Cafe". If you stop by, we'd be thrilled if you could add your own surprising or perplexing "my kid's behavior" to the collection!

【Overview】

"Secret Kids Encyclopedia" Exhibition & Submission Period: Tuesday, September 10th - Sunday, October 6th

Venue: ITOCHU SDGs STUDIO Children's Perspective Cafe

(Itochu Garden 2F, 2-3-1 Kita-Aoyama, Minato-ku, Tokyo)

Hours: 9:30 AM - 5:30 PM (Last Order 5:00 PM)

Closed: Mondays (If Monday is a holiday, closed the following business day)

Access: 2-min walk from Exit 4a of Gaienmae Station (Tokyo Metro Ginza Line), 5-min walk from Exit 1 (towards Kita-Aoyama) of Aoyama-itchome Station (Tokyo Metro Ginza Line, Hanzomon Line, Toei Oedo Line)

*For details, please visit the official website.

※You may need to wait in line during busy times. If the wait exceeds 1 hour, we will post updates on the crowd situation via our official Instagram Stories.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Makiko Umeda

Dentsu Inc.

Marketing Division 3

Planner

After working as a reporter at a broadcasting station, she joined Dentsu Inc. She has long been involved in planning promotions, including in-store sales promotions, events, PR, and social media initiatives, and has also handled children's products such as diapers and baby food. She is the mother of two daughters, ages 5 and 3.

Hitomi Sato

Dentsu Inc.

Creative Planning Division 5

Copywriter

After working as a media manager for Facebook and LINE in the Digital Business Division, I transferred to the Creative Division. I handle planning and development focused on copywriting. I love radio and Haruki Murakami. Awarded at ADFEST, JAA, Mainichi Advertising Design Awards, CCN Awards, and others. Mother of two daughters, three years apart.

Yoko Okamoto

Rissho University

Department of Child Education and Welfare, Faculty of Social Welfare

Professor

Specializes in developmental psychology. Research focuses on parent-child communication, childcare and early childhood education abroad, and parenting support. Major publications include "Transition to Parenthood from Pregnancy through Infancy: Parents Who Develop Through Parent-Child Interaction" and co-authored works such as "Psychology for Childcare: Learning Through Episodes."