"ART for Medical" is a medical × art project being researched by the Department of Physiological Regulation at Showa University School of Medicine and Dentsu Inc. It aims to use the power of art to make healthcare more accessible and enjoyable, thereby improving QOL (quality of life).

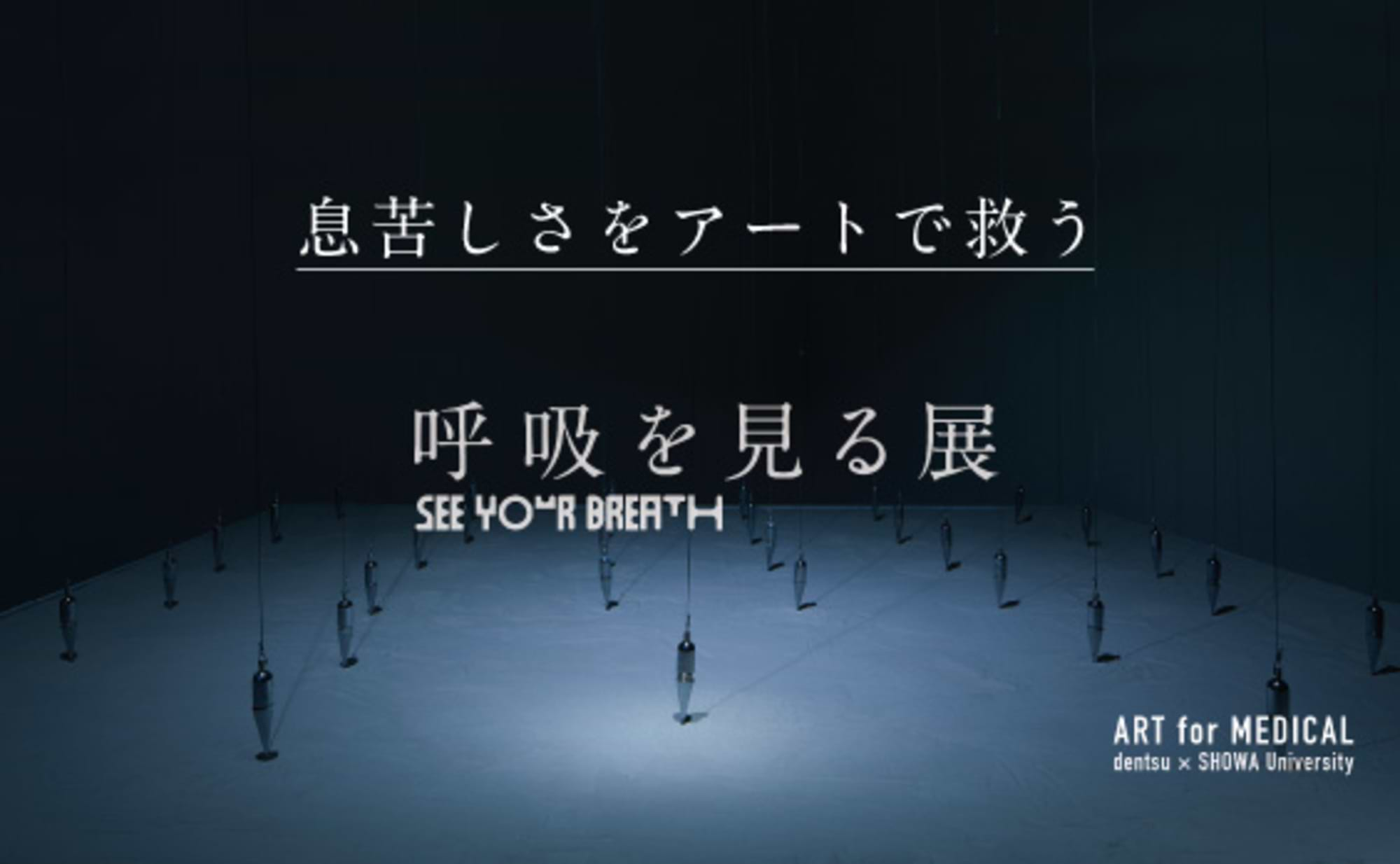

The first challenge was the exhibition "Seeing Breath," a media art installation (*) that visualizes breathing to help regulate it.

This time, Momoka Nakayama of Dentsu Inc., who was involved in the production as a creative technologist, interviewed Dr. Miku Kosuge. Dr. Kosuge not only works as a researcher but also faces patients daily as a physician in respiratory medicine. We asked her what she felt while experiencing the work as a project member and about the potential of medical × art from a physician's perspective.

※=Media Art

Artworks utilizing digital technology

【"Seeing Breath" Exhibition Overview】

<Held at Showa University Kamijo Memorial Museum until March 22, 2022>

A media art exhibition themed around "Visual Breathing Rehabilitation," which visualizes unconscious breathing to draw awareness to it and help regulate breathing.

Organized by: Department of Physiological Regulation, Division of Physiology, Showa University School of Medicine / Yuri Masaoka & Sponsored by: Showa University Kamijo Memorial Museum Emiko Oguchi / Yuichi Yamamura Showa University School of Medicine

Department of Physiology, Division of Physiological Regulation, Supervision: Masahiko Izumisaki / Motoyasu Honma / Shotaro Kamijo Creative Director: Kentaro Suda Art Director: Yu Takahashi

Creative Technologist: Momoka Nakayama Artwork Provided "Iki-Utsushi": Yukiya Yamane/Hanako Yano Graphic Production: Mao Fujimoto/Miyuki Imai/Ayano Ito (ADBRAIN) Space Design Production: Hitomi Nakazawa (CBK)

There is room for art to intervene in medicine

Nakayama: For the "Seeing Breath Exhibition," we carefully considered how to visualize breathing and output it as art when creating the works. Dr. Kosuge, I'd like to hear your perspective on this exhibition from a physician's viewpoint. First, could you tell us about your specialty?

Kosuge: I conduct research as a graduate student in the Department of Physiological Regulation at Showa University School of Medicine, while also serving as a physician in the Department of Respiratory Medicine at the affiliated hospital. As a physician, I treat all respiratory diseases, including lung cancer, infectious diseases like pneumonia, chronic respiratory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and interstitial pneumonia, and allergic diseases like asthma.

Nakayama: Among the works you experienced this time, what were your impressions of "SEE YOUR BREATH," which visualizes breathing as a circle?

"SEE YOUR BREATH"

A 2D work where circles projected onto a screen synchronize with your breathing.

Kosuge: Seeing the circle grow larger helped me visualize my lungs expanding, which made breathing feel easier.

Nakayama: Professor Masaoka, whom we interviewed in the first session, mentioned that he is actively pursuing research aiming for practical application in rehabilitation.

Kosuge: I think this work could be applied in clinical respiratory rehabilitation settings. However, verification involving a certain number of people, including healthy individuals, would be necessary. In reality, I imagine each person would have different reactions.

Nakayama: Visualizing it would be interesting to see the differences in individual responses. Now, what about "SEE MEDICINE," the piece where a pendulum moves in sync with breathing?

"SEE MEDICINE"

A 3D work where a suspended pendulum moves in sync with the participant's breathing, creating sand art based on its trajectory. It not only reflects the participant's breathing but also displays the diverse breathing trajectories of 33 individuals as sand art.

Kosuge: Focusing on the rhythm of my own breathing and the pendulum's movement was incredibly relaxing mentally. I think it might also have an effect of boosting concentration.

Nakayama: In "SEE MEDICINE," the pendulum moves toward you when you inhale and away when you exhale. The horizontal axis moves steadily at the average human breathing cycle of 12 breaths per minute. If the participant's breathing is steady, a beautiful figure-eight trajectory is drawn in the sand spread beneath the pendulum.

Kosuge: Unlike the first piece, this visualizes breathing rhythm rather than lung capacity. It gives the impression of regulating breathing rhythm. People with respiratory conditions often have shallow, rapid breathing, but this could guide them toward slow, deep breaths.

Nakayama: Since most people's breathing isn't constant, the breathing patterns drawn in the sand art take various shapes. Breathing speeds up or slows down, so the same pattern never repeats. Gradual shifts occur; some participants' sand art formed flower-like shapes instead of figure eights.

Kosuge: Breathing isn't fixed at exactly 12 times per minute, so it's not a problem if the sand art is broken. However, if using it for effective therapy, as training to maintain a steady breathing rhythm, it might be good to instruct them to aim for a clean figure-eight trajectory.

Nakayama: What about the "in-out" aspect?

"Breath-Transfer"

A work where paintings displaying expressions of joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure synchronize with your own breathing. You can physically experience how the emotions conveyed by the paintings' expressions are transmitted through your breath.

Kosuge: There's a visual appeal in the paintings synchronizing with your own breathing, isn't there? Furthermore, I thought the idea of the glass fogging up with your breath was brilliant. As with all the works, the mechanism detects chest movement during breathing using a worn band or sensor, so there's no risk of droplets spreading. It's also great that it can be implemented with infection control measures in place.

The Potential of Medical Data × Media Art

Nakayama: This time, we challenged ourselves to convey medical respiratory data as media art. From a physician's perspective, what kind of artworks could be utilized in medical settings?

Kosuge: Among diseases causing chronic respiratory failure, COPD and interstitial pneumonia are representative examples, but these two conditions are fundamentally different. COPD involves long-term smoking damaging lung tissue, causing it to expand and narrow the airways, leading to breathlessness. Interstitial pneumonia, however, is a disease where the lungs harden and shrink for some reason, making it difficult to breathe in. It's hard for patients to grasp this difference, so it would be great if artworks could visualize aspects like lung stiffness or volume.

Nakayama: In clinical settings, spirometry is used to observe breathing volume and the waveform of inhalation and exhalation. However, this visualization is primarily for doctors to interpret. Art could be a useful method to convey these numerical values to patients.

Kosuge: For COPD and asthma patients who struggle to exhale, we use the amount of air exhaled in one second—known as the FEV1 or forced expiratory volume in one second—as an indicator for diagnosis and severity classification. For patients with interstitial pneumonia, the lungs become stiff, making it difficult for oxygen to diffuse within the lungs. Therefore, there are also tests that measure diffusion capacity. There is a lot of respiratory medical data beyond just lung capacity, and I think there is great potential for using art to make it easier for patients to understand.

Furthermore, in COPD, respiratory rehabilitation is emphasized as a treatment method, considered equal to or even more important than drug therapy. Currently, it is common to perform exercises such as "pursed-lip breathing" training, respiratory muscle training, and physical training like long-distance walking.

"Pursed-lip breathing" is a rehabilitation technique used when airways narrow and exhalation becomes difficult. By pursing the lips while exhaling, airflow is restricted, increasing flow velocity and making exhalation easier. Since all rehabilitation depends on the patient's motivation and physical strength, visualizing breathing, as in this exhibition, could make rehabilitation more enjoyable and engaging even for those who find it tedious.

Using Art to Make Healthcare More Accessible

Nakayama: Moving forward, I envision creating spaces where people can access maintenance and healthcare just before needing a full medical checkup, facilitated through art. These would be places that spark opportunities to confront one's own health. For instance, within the framework of an art exhibition, offering mini-checkups could bring healthcare much closer to everyday life.

Kosuge: People's approaches to health are truly individual—some get frequent checkups, while others never come. However, checkups can detect lung diseases through X-rays and screen smokers for lifestyle disease guidance, so access to checkups remains crucial. It would be great if ideas to draw attention to this became reality.