Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

"From Kyushu to Space." How to do what no one has done before!

Left: Toru Suzuki (President and Representative Director, Dentsu Kyushu Inc.)

The potential of the "space business" is now beyond doubt.

This time, Dentsu Kyushu Inc. President Toru Suzuki spoke with Shunsuke Onishi, President and CEO of QPS Research Institute in Kyushu.

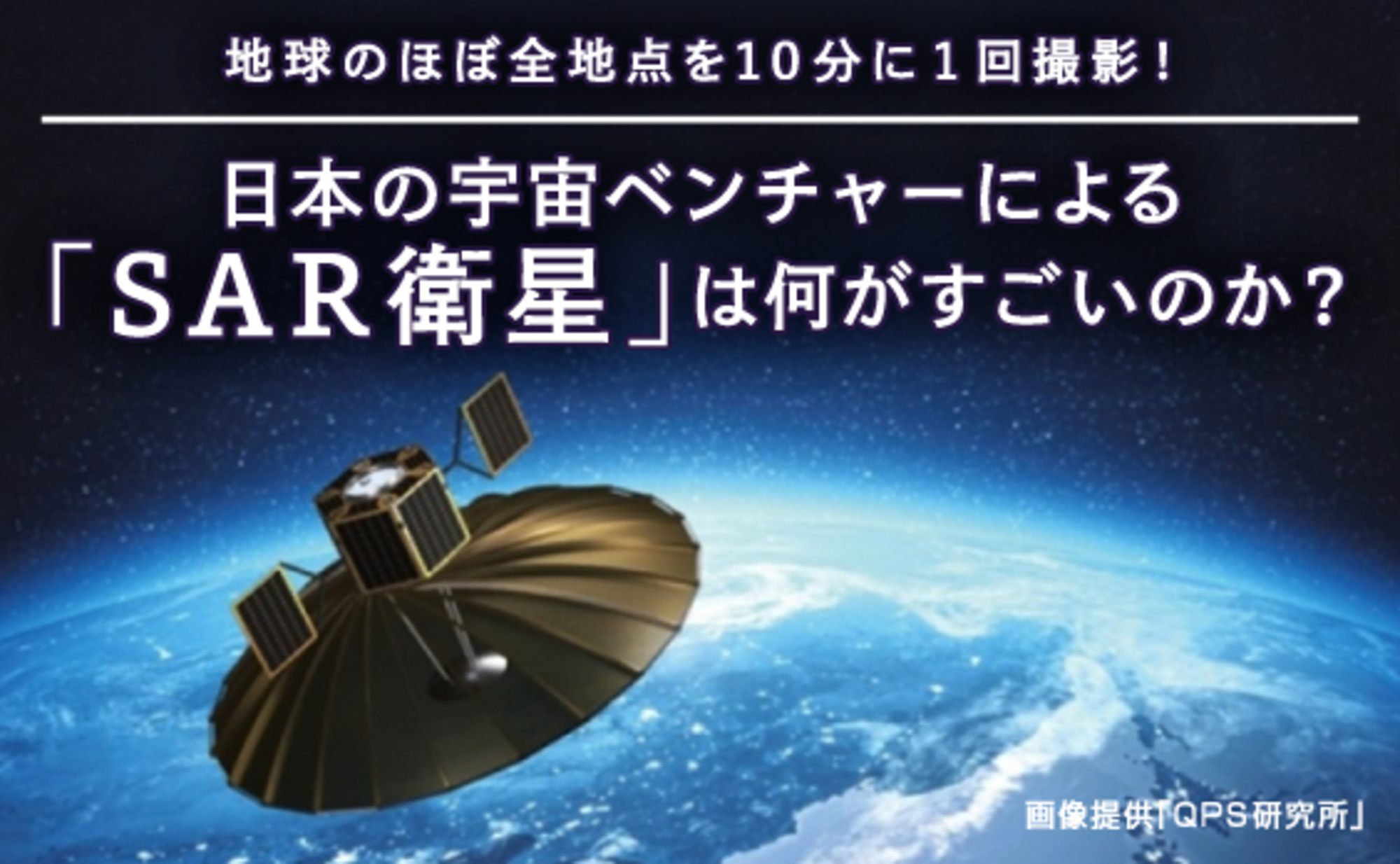

QPS Research Institute develops and operates "Small Radar Satellites (SAR Satellites)" equipped with "Synthetic Aperture Radar" capable of observing the Earth's surface even at night or in bad weather. This pioneering challenge was recognized with the "5th Space Development and Utilization Grand Prize - Prime Minister's Award" (sponsored by the Cabinet Office, March 2022).

This conversation offers courage to us all as we face an uncertain future.

(Text: Dentsu Kyushu Inc., Kei Yamamoto)

<Table of Contents>

▼Establishing the Space Industry in Kyushu Through the New Challenge of the "Small SAR Satellite"

▼ A Kyushu Project Driven by Kyushu's Identity

▼Identifying "What We Can Do in the Next Frontier"

▼Space Remains Unaffected by Events on Earth!

▼Creating New Demand by "Cross-referencing" Ground-based Big Data with Satellite Data

▼Japan's Space Development is the "Power of Combination." Kyushu's Strength Lies in Making This a Reality

Establishing the Space Industry in Kyushu Through the New Challenge of "Small SAR Satellites"

Suzuki: Please tell us about the founding of QPS Institute.

Onishi: It was established in 2005 by Professor Tetsuo Yasaka, who founded the laboratory I belonged to at Kyushu University, and others. The goal was to establish the space industry here in Kyushu.

Kyushu has rocket launch sites at Tanegashima and Uchinoura in Kagoshima Prefecture. However, the rockets themselves and the satellites they carry were manufactured in the Kanto and Tokai regions. In other words, Kyushu originally had almost no companies involved in space.

Suzuki: Even so, Kyushu has universities teaching space engineering and many manufacturing companies. The foundation for space development exists, so the company was established to help it take root here.

Onishi: Yes. At that time, small satellite projects were booming in universities. They were particularly active in the US, Europe, and Japan. I was also involved in satellite development at university under the guidance of Professor Yasaka and others.

However, "university satellite projects" faced challenges. Students typically rotated every two years, making the "transfer of knowledge" from seniors to juniors difficult. Students graduated, and besides development, they had their academic studies, leaving little time for proper succession. Furthermore, even if students designed a satellite, manufacturing it entirely on their own was also difficult.

Therefore, Professor Yasaka and his team reached out to local manufacturing companies, inviting them to participate in satellite construction. To successfully guide a satellite development project, learning from failures is crucial. They aimed to share these failure experiences with local company personnel and accumulate that knowledge within the companies themselves. As a result, the sweat and effort invested alongside numerous local companies back then became the foundation for today's QPS Institute.

Suzuki: So, as companies accumulate knowledge, new students can learn from them each time, right?

Onishi: However, even after studying hard at the university or QPS Research Institute, graduates who wanted to work in space had no choice but to leave Kyushu at that time. Back then, Kyushu's space industry was nowhere near the scale of a viable industry.

I found myself in the same situation in 2013, which is when I aspired to join QPS Research Institute. My desire was to inherit the foundation and vision the professors had built, sustain the company, and create a place where future graduates and even alumni who had left could return.

Suzuki: Are there actually people who come back?

Onishi: Yes. However, to make it a place people would want to return to, I believed we needed to take on new, compelling projects that no one else in the world was attempting.

Looking at global space development at that time, small observation satellites using cameras, or "optical satellites," were being developed both domestically and internationally. However, no one was working on "small radar satellites (SAR satellites)" (*), so we set our sights on developing these.

※Related articles on radar satellites

Is Space Profitable!? Insights from the Development Front Lines. [Satellite Data Edition]

Suzuki: Even for observation satellites gathering ground data, conventional satellites use optical systems—meaning cameras—which have weaknesses like "inability to capture images at night" and "clouds obstructing imaging during bad weather." That's why you focused on the need for radar satellites, which observe by emitting radio waves toward targets.

Onishi: Yes. As a result, I believe this new challenge captured the interest of our seniors and professors who came from Kyushu, as well as everyone at Kyushu-based companies.

A Kyushu Project Driven by Kyushu Identity

Suzuki: Beyond these "staff who returned to Kyushu," over 20 local companies, including the NPO Enjin Space Engineering Team, have become partners of QPS Research Institute, collaborating on radar satellite R&D.

Onishi: The fact that dozens of companies can collaborate like this today stems from the founders reaching out to each company individually in the early 2000s, asking, "Would you like to enter the space industry?" and everyone starting out on their own. Over the past decade or so, a solid foundation has been built for the space industry to develop in Kyushu. This solidarity is an irreplaceable asset.

Suzuki: The motivations of those who gathered around this vision seem driven not only by "challenging the unknown" but also deeply tied to an identity of "being born and raised in Kyushu." Kyushu has seven prefectures, each with distinct cultures, yet when we unite toward a common goal, we generate tremendous power. It's that sense of "Let's do this because we're Kyushu." I feel there's something uniquely Kyushu about these region-wide projects.

Onishi: For example, in Hokkaido, Hokkaido University and Uematsu Electric are jointly developing rockets. Even as a student, I thought this kind of relationship was fantastic. And now, in Kyushu, multiple universities and multiple companies are working together in a multi-dimensional way on space development. I don't think there's another region like this.

Identifying "what we can do in the next frontier"

Suzuki: When development began, no one was working on small radar satellites.

Onishi: First, the most common "large optical satellites" using optical cameras included Japan's well-known "Himawari weather satellites." Then there were "small optical satellites" like those from Axelspace (※).

There were also "large radar satellites," like JAXA's "ALOS-2 (Daichi 2)." However, looking worldwide, development of "small radar satellites" was not progressing.

※Related article on Axelspace

Deriving Insights from Satellite Imagery! Space is the Turning Point for Marketing Evolution

Suzuki: Did you think small radar satellites would be the next step?

Onishi: Yes. Roughly three-quarters of the Earth is covered by nighttime or bad weather, but radar satellites can observe anytime, regardless of day/night or weather conditions. If we could miniaturize that capability, I believed it would become an attractive project the world hadn't seen yet. First, weight directly impacts launch costs, so miniaturization and weight reduction would lead to significant cost savings.

Later, Vice President Toshimitsu Ichiki proposed: "Smaller radar satellites would make multiple launches more cost-effective than conventional ones." He also suggested: "Building a constellation (a group of satellites operated as a single system) could enable near-real-time observation of nearly every point on Earth." He envisioned that knowing what's happening on Earth almost instantly could contribute to future society in various ways.

Suzuki: The fact that they didn't exist before suggests the technical hurdles were high. Were you confident in developing them?

Onishi: Research on small radar satellites themselves was progressing worldwide, but there were hurdles: the need for large antennas and significant power consumption. We believed the key breakthrough lay in "whether a large parabolic antenna could be mounted on a small satellite." When we asked Professor Yasaka about the feasibility of such an antenna, he replied, "It can be done."

Suzuki: "It can be done"? That's incredibly cool.

Onishi: Before joining the university, Professor Yasaka worked at NTT's research lab, developing broadcast and communications satellites. He was Japan's foremost authority on parabolic antennas. That's likely why he could envision one fitting on a small satellite. If it was theoretically possible, then it was just a matter of taking on the challenge. Our scope naturally focused on "what we could achieve in the next frontier."

Space is unaffected by the various events happening on Earth!

Suzuki: Dentsu Kyushu Inc. had the honor of creating the mission marks for the first satellite launched in 2019 and the second in 2021. What are the plans for the third satellite and beyond?

QPS Laboratory Mission Emblems. Top: Unit 1 Izanagi Bottom: Unit 2 Izanami

QPS Laboratory Mission Emblems. Top: Unit 1 Izanagi Bottom: Unit 2 IzanamiOnishi: We are currently operating Units 1 and 2. This year, we are raising funds (Note: Cumulative funding as of February 8th is ¥8.25 billion) and plan to launch four more satellites. We intend to launch multiple satellites annually, aiming to establish a constellation of 36 satellites by 2025 or later. Achieving this will enable us to observe virtually any location on Earth at an average interval of 10 minutes.

The "number of satellites" and the "frequency of imaging" are correlated; the more satellites in the constellation, the more frequently we can observe. The imaging frequency changes depending on the number of satellites—it could be once per hour, once every 30 minutes, and so on.

Our current goal is to achieve "once every 10 minutes" with a 36-satellite constellation. However, if a need arises in the future, such as "observing once every minute," we could meet that demand by launching more satellites.

Suzuki: The ability to observe the ground anytime, regardless of time of day or weather, would be beneficial for security and infrastructure management.

Onishi: Yes. Additionally, it plays a major role in disaster prevention. Natural disasters have become more frequent in recent years, but we never know when or where they will strike, and many occur at night when optical satellites cannot capture images.

In the initial stages of rescue operations, data on the disaster situation provided by SAR satellites is extremely effective. Space is unaffected by the various events occurring on the ground. I believe data from radar satellites will become one of the foundations enabling people to live with peace of mind.

Suzuki: Recent years have seen a succession of disasters, such as torrential rains caused by linear precipitation zones and the recent undersea volcanic eruption in Tonga. With real-time satellite data, we can predict what has happened and what impacts will occur within tens of minutes or hours, even for such disasters.

Onishi: First, understanding the current situation—knowing what is happening now—is crucial. Then, as this information accumulates, we can predict what will happen next.

Creating new demand by "combining" ground-based big data with satellite data

Suzuki: Could you tell us about your current strategic partners?

Onishi: In December 2021, we received funding from SKY Perfect JSAT and Nippon Koei. Simultaneously, we formed business alliances to develop services utilizing satellite data.

We also have an "Infrastructure Monitoring" initiative with Kyushu Electric Power. For example, we are exploring with JAXA whether satellite data can be used for regular inspections of power plants or for assessing situations during disasters. As the working population declines, there is high expectation that using satellites will lead to greater efficiency and labor savings.

Suzuki: Beyond disaster and infrastructure management, combining this with terrestrial big data seems poised to create new services.

The Dentsu Group has set the goal of being an "Integrated Growth Partner" for the sustainable growth of our clients and society. Our objective is to generate business ideas, accompany clients, and realize their visions. For example, we believe we can support companies' sustainable growth by combining the consumer data and systems held by the Dentsu Group with the "eye in space" provided by SAR satellites.

Onishi: Combining space data with terrestrial big data hasn't been possible until now. One reason is the difference in "temporal resolution."

Ground data updates frequently—every few seconds, minutes, or hours. In contrast, traditional space data came weekly or monthly, and not even at regular intervals. That made synchronizing ground and space data difficult.

However, as we build constellations and increase the number of satellites, the temporal axes of ground and space data will align significantly. The intervals will also converge to roughly "once every 10 minutes," greatly enhancing their compatibility.

Suzuki: Currently, led by Dentsu Kyushu Inc., the Dentsu Group is in discussions with Fukuoka Prefecture, Fusic (a leading AI company in Fukuoka), and JAXA regarding proof-of-concept experiments for marketing utilizing satellite data. For example, predicting the peak season for vegetables using satellite data to create demand. We believe that by improving accuracy, this could contribute to enhancing agricultural production and reducing food waste.

Onishi: No matter what events occur on the ground, satellites can consistently acquire data at any time. Whether it's farm fields or disaster sites, using satellites to "view from above" is crucial. As you mentioned, satellite data is also an important piece for supply-demand coordination and demand creation.

In January 2021, we launched our second satellite, Izanami, aboard a SpaceX rocket from the US. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, movement restrictions were in place. Being largely confined, I was reminded anew: "At times like this, satellites are absolutely vital for obtaining information from distant locations."

Japan's space development relies on the "power of combination." Kyushu's strength lies in realizing this.

Suzuki: QPS Institute's purpose is stated as "Expanding the possibilities of space and contributing to human development." Its value is described as "By tackling essential and original ideas with crazy thinking, we excite people and contribute to the development of Earth and humanity." This "exciting people" part is wonderful. Bigger dreams bring greater happiness when realized, right?

Onishi: True to that value, we want to do things no one has ever done before. I believe Kyushu provides the foundation for that. Back in 1970, during the dawn of Japan's space development, Japanese universities and companies came together to build the "L-4S" rocket and launch "Osumi," Japan's first satellite. There were no space companies back then; it was created by combining technologies brought together by various companies and researchers.

Professor Yasaka knew this "power of combination" from experience. So, he didn't fixate on whether companies or researchers in Kyushu had prior experience manufacturing space equipment. He simply reached out to them. And that's how "people who challenge" came together.

Even without prior space development experience, each possessed brilliant technology. We centered discussions around that technology, debating how to proceed. Crazy ideas were welcome. Eventually, our vectors aligned, and we created what we wanted. I believe this is our strength, Kyushu's strength.

Suzuki: Amidst the negative atmosphere in society, I want to create as many projects as possible that excite people, propel them to the next stage, and give them courage. Especially for the development of the Kyushu regional community. Let's get moving together. Thank you for today.

《Postscript》

Behind the development of the small radar satellite lay Kyushu's identity and its singular foundation in manufacturing.

"We want to establish a space industry here," "We want to pass on knowledge," "We want to create a foundation for people to return to their hometowns." I realized that such a "flame of passion" is crucial for new challenges.

"Even without prior experience, they possess something brilliant. We discuss how to proceed centered around that." "Eventually, we hope the vectors align and something comes together." I feel this is the process for realizing not just satellites, but any business idea. It's an essential truth unaffected by the times or technological progress.

The Dentsu Group also values this principle. Kenichi Mizuno, Head of New Business Development at Dentsu Kyushu Inc., states:

"We will act to utilize space data and realize an exciting society. We would be delighted if more supporters join us and if we can contribute to the development of QPS Institute."

Dear readers, why not join us in unleashing the "power of combination"?

(Yamamoto)

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Yamamoto Kei

Dentsu Kyushu Inc.

Essential Marketer / Producer / Chief Director for Space Business Creation Promotion

Member of the specialized team 'Dentsu Space Lab,' which handles a wide range of activities from collaborations with JAXA to supporting space venture businesses. Around 2005, he met manga artist Leiji Matsumoto, originally from Fukuoka, who was then Chairman of the Japan Space Cadets promoting space education activities. Since then, he has consistently worked under the theme of "making space a reality for business." Even now, alongside diverse client work unrelated to space, he dedicates equal effort to space-related endeavors, actively focusing on marketing support for food and agriculture utilizing satellite data.