Ayaka Yagi, an art director formerly of Dentsu Inc. who now leads the independent agency "Arens," has published a book titled "Design at the Heart of Management." Drawing on her own experience, she meticulously explains the significance of involving an art director early in the process of branding corporate organizations and products.

Alongside numerous case studies, it outlines concrete work steps, making it a useful guide for practitioners to keep on hand and use to check project progress. However, the essence of this book seems to lie a bit deeper.

In the final chapter, Yagi outlines the "three criteria" she values most in branding work.

The first is "Beauty." Precisely because we live in an era where designs can be easily created using off-the-shelf services or stock photos, he advocates for a professional stance that pursues "truly moving beauty" that cannot be mass-produced. The second is "Can it make the future better?" As a partner in brand creation, he emphasizes the constant awareness of ethical considerations.

And the final one is "Does it lead to profit?" He points out that we should check whether design, which is an investment for companies, actually brings proper returns. While this third point may seem obvious, it's also true that in the real world, some designers avoid the topic by saying, "I don't really understand money matters."

Typically, branding work involves forming a team where specialists handle data analysis, logo design, PR, financial management, and other tasks through division of labor. However, Mr. Yagi reportedly embeds himself "solo" within the client organization, providing integrated direction across all aspects of branding. Rather than settling for a designer's self-satisfaction of "it turned out beautiful, so that's good," he actively engages with the revenue side, fighting alongside the client as a "fellow crew member on the same boat."

This brings to mind the words of architect and entrepreneur Taro Kagami, also a former Dentsu Inc. employee, who sounded an alarm about Japanese design education by comparing it to his alma mater, Harvard University.

"Design is great. But who's going to pay for it?"

To put it bluntly, an architect's work can be divided into two parts: "raising money" and "designing and supervising buildings." However, Japanese architectural education completely ignores this monetization aspect, which accounts for 50% of the job. As a result, we frequently see situations where people who were astonishingly talented in university drafting assignments struggle to secure work after graduation, barely scraping by on small-scale projects.

In American architectural education, presentations are required that encompass the entire financial flow until the building is constructed, the quality of tenants, and the business sustainability of the activities conducted there. Notably, about 30% of urban planning professors also hold positions in public policy graduate schools. This revealed that the entire university understands how involving the government in fundraising significantly impacts urban design.

Thinking about it, it's obvious, but compared to Japanese design education, which often views discussing money as taboo, this was a very striking observation.

(Excerpted from [Continued] Local Gurguru #116 : "Harvard's Design Education" )

It's precisely because Mr. Yagi himself overcame these limitations one by one through his extensive experience as an art director that each story introduced in this book carries such impact.

On the other hand, to be honest, I never fully grasped the concept of "branding design," which is also used in this book's subtitle.

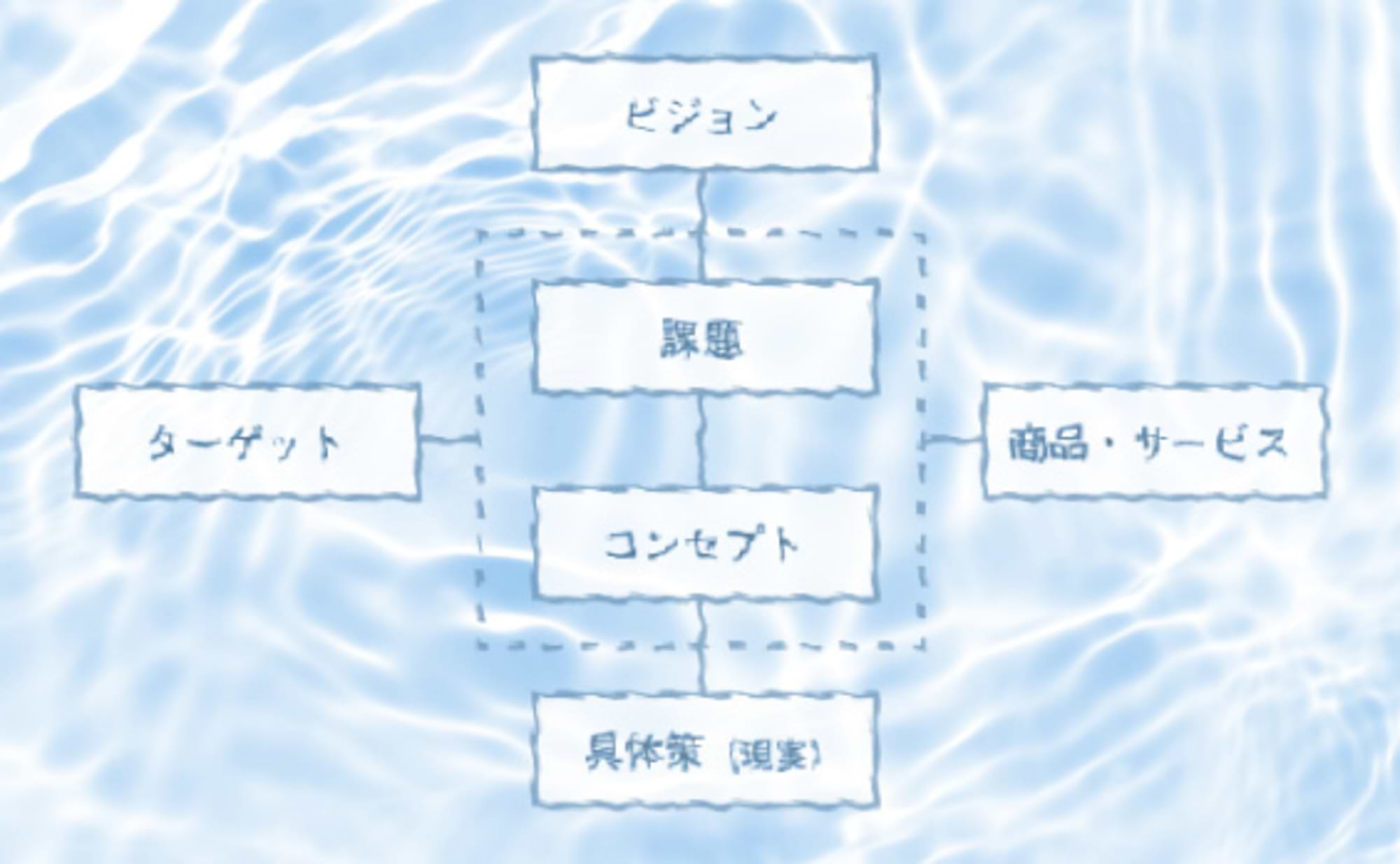

This is because "design" (at least in its "broad sense") refers to two actions: "clarifying intent" and "giving it form." And branding, borrowing Mr. Yagi's own description, is "expressing the intent of 'authenticity' through form (using names, words, symbols, designs, etc.)." In other words, the concept of "branding" should inherently include "design."

If executives want to do "branding," they must take the "design" steps shown in this cycle on their own—regardless of whether an art director or designer is present.

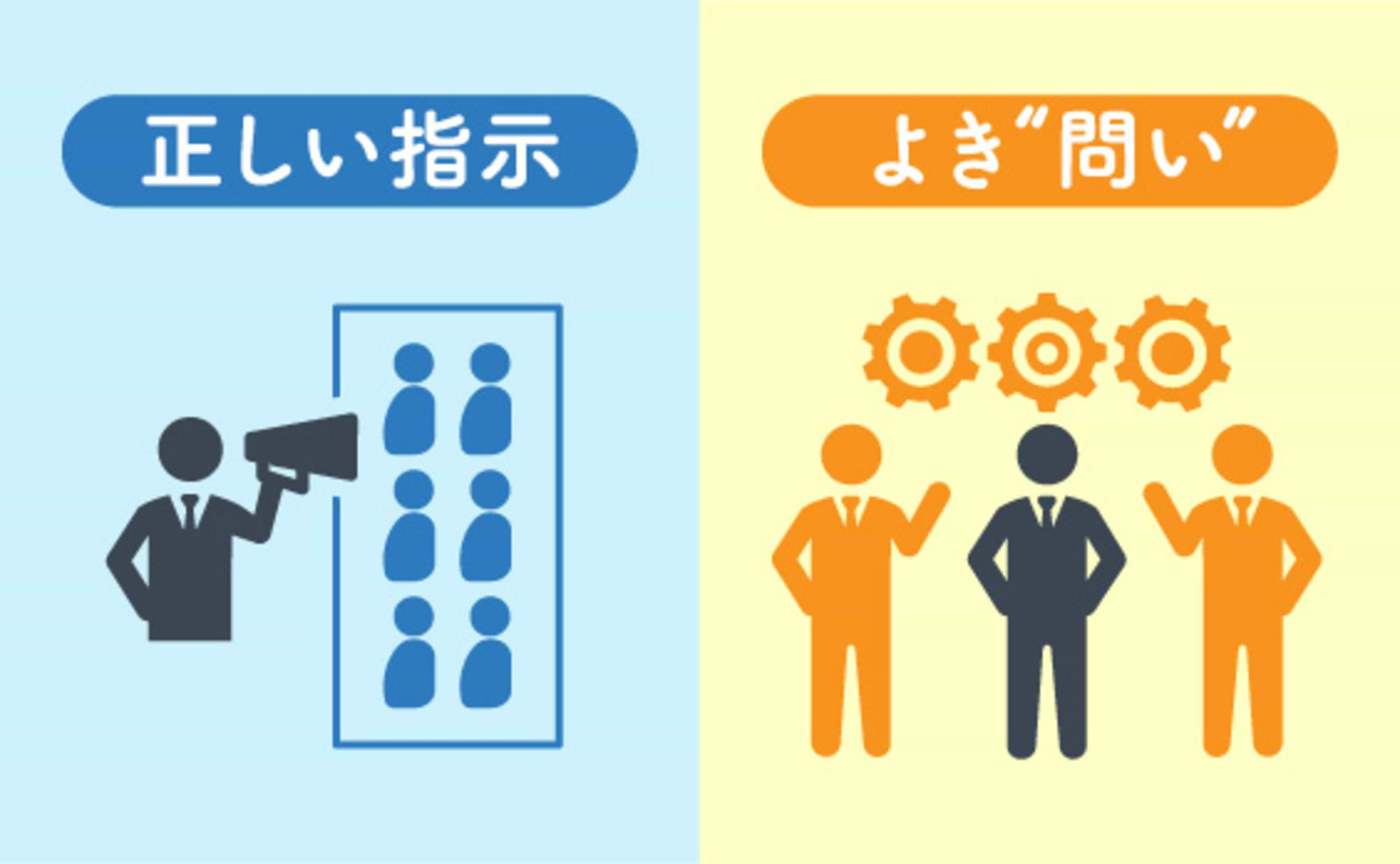

I suspect what Mr. Yagi intended to convey in this book is a highly practical message (especially for those who rarely interact with advertising agencies): "Having an art director as a consultant for the brand owner (≈ the business owner) can be beneficial."

However, in an era where concepts like "design thinking" risk being consumed as buzzwords without grasping their essence, I find myself hoping for greater depth in future discussions about the true nature of "design" as a knowledge-based methodology. My anticipation for Mr. Yagi's future contributions grows.

Now then.

Some time ago, I hosted a dinner at my place with Yagi-san, Kagami-san, and other delightful friends. The main dish was nearly 2kg of Black Angus beef chuck roast, slow-cooked in a heavy skillet. We paired it with chimichurri sauce (a BBQ dressing famous in Argentina, made with parsley, garlic, oregano, paprika, etc.).

The topic was supposed to be something lofty like "What is design, anyway?" but things got so lively that my memory is hazy now...

We must gather again soon to deepen our "dialogue."

Enjoy your meal!