Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

How can we create business opportunities within the circular economy?

"The circular economy isn't profitable."

"Even with a good concept, the hurdles to implementation are high"

"Too many stakeholders get in the way of progress"

These are common concerns we hear.

How can we quickly engage others? How should outcomes be designed? In this article, we hear from Mr. Osamu Furuichi, who formed a new design team at Taisei Corporation integrating design and lab functions to tackle circular economy implementation, and Mr. Daiki Sato from the Technology Center, sharing case studies. The interviewer is Tomoyuki Oka from Dentsu Inc.'s Sustainability Consulting Office.

<Table of Contents>

▼How to Exceed Customer Expectations?

▼Experiences Bridging Real and Virtual Worlds Create Value

▼The Significance of "Zero Carbon Buildings" as Social Experimentation Sites

▼Building Solid, Profitable Business Designs Starting with Small Economic Circles

How to Exceed Customer Expectations?

──When I consult on new ventures as a service designer, I often encounter situations where "the concept is interesting, but they can't convince the company internally about the investment and can't move forward." I'd like to ask how you engage others from conception to implementation, and how you handle funding. First, what kind of work do you two typically do?

Furuichi: Originally, my main work in design was "responding to client requirements," and I was in a department that didn't do business development. But when Mr. Sato from the Technology Center started asking me, "Got any interesting ideas?" we ended up collaborating more and more. Later, I co-founded the "Advanced Design Office" with young designers, now in its fourth year. This office is a specialized design team combining both design and lab functions. Previously, no department handled both design and research simultaneously. We felt a bridging team was essential to accelerate value creation projects, leading to this new team's formation.

──How did you convince the company that a new organization was necessary?

Furuichi: Our company's style is to make new proposals that absolutely exceed customer needs. I proposed internally that this kind of team was necessary to pursue agile development. Work that merely organizes and shapes existing requirements struggles to surpass customer needs, so we aim to create things that exceed customer expectations.

Sato: Around the same time we launched the Advanced Design Office, a department promoting innovation was also established within the Technology Center. This was to tackle societal challenges beyond traditional needs through open innovation, and we hoped this approach would also drive success in competitions.

Furuichi: The Advanced Design Office prioritizes collaboration both inside and outside the company. Through Sato's network, we were introduced to many people. Sato is an innovation hub connected to diverse engineers working on drones, autonomous driving, and more. Having designed across diverse fields—residential, office, research institutes, factories, pavilions, and urban planning—I also possess a network as a design hub. Since I lecture at universities, when opportunities arise like "We want students to participate in field tests," I reach out with "Would you like to collaborate on research at XX University?" and advance projects alongside university professors.

Experiences bridging the real and virtual worlds create value

──Wasn't the initial theme "Circular Economy"?

Furuichi: The Advanced Design Office handles many proposals utilizing digital technology. We started with the "Digital Nishi-Shinjuku Project," which combined a large-scale model (about 5m x 3m) with digital technology (AR). Through this project, we're applying insights gained from urban area pilot tests to the Iwami Ginzan project in the regional area of Shimane Prefecture. Today, as circular economy examples, I'll introduce the "Iwami Ginzan Digital Twin," "Our Company's Zero-Carbon Building," and the "Vortex City Project."

──Could you also share insights gained from the "Digital Nishi-Shinjuku Project"?

Furuichi: In architectural digital twins (technology that recreates the real world digitally), it's common to digitally replicate and verify "visible, tangible parts" like floors, walls, and ceilings. We thought, why not try to recreate the entire environment, including invisible phenomena like wind and sound? That's how the idea to create a "digital twin" that digitally recreates the entire urban environment began.

The "Digital Nishi-Shinjuku Project" used the Technology Center's simulation technology to recreate phenomena like flooding during torrential downpours around the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building in Shinjuku and pedestrian flow during evacuations to Shinjuku Central Park from a disaster prevention perspective. We advanced this project through collaboration with various companies and universities, even making voluntary proposals to the Tokyo Metropolitan Government.

──Specifically, how did you do this?

Furuichi: We built a massive model replicating Nishi-Shinjuku. Using an app developed with Honeycomb Lab Inc., you could hold a tablet over it and see the simulation in AR. We visualized things like, "This spot actually floods during torrential downpours." This lets us verify where flood barriers are needed. Based on that, we can partner with companies that build flood barriers and propose disaster prevention plans to local governments. We also tested a drone-based voice evacuation guidance plan for disasters with drone companies, identifying areas where sound reverberates in building clusters, hindering effective voice guidance. Additionally, we collaborated with signage companies to verify the effectiveness of dispersing pedestrian flow through simulations by varying digital signage placement.

──Combining physical models with digital elements increases the resolution of the experience, which seems likely to generate concrete ideas. If experience design is confined to a smartphone, it just feels like "Oh, this is what it's like," and doesn't generate much excitement.

Furuichi: In a "roundtable style" setup around a model, people naturally start conversations like, "What's happening over there?" when they see what their neighbor is looking at. This sparks new collaboration ideas, so combining real and virtual experiences is crucial. I believe these serendipitous encounters between virtual and reality make urban design discussions more exciting. It also creates value, both short-term and long-term, for building consensus among various stakeholders.

──How were the insights gained applied to other areas?

Furuichi: While urban areas are actively adopting digital technologies, many rural regions haven't even begun introducing digital tools, let alone 3D modeling. When we sought to test digital twins in areas contrasting with cities, we received an invitation from the Iwami Ginzan area in Shimane Prefecture. This led to a project utilizing the Digital Rural City Nation Concept Grant.

In Iwami Ginzan, we started by collecting point cloud data of the entire town using drones to create a 3D model of the streetscape. We recreated this model on the metaverse platform of One2Ten Inc. We are developing technology where generative AI learns area information like local history and culture. When you hold a tablet over the site, it identifies buildings based on location data, and a street guide AI provides navigation.

Of course, users can also virtually stroll through the town via VR remotely to learn about it. We are also considering its use as educational material. Where regional information is missing or insufficient, we are exploring a system developed with Tō Corporation where AI poses reverse questions, encouraging local elementary and junior high school students to fill in the town's information. This initiative aims to simultaneously achieve the preservation of historical value and information while revitalizing the region, evolving into an effort to cultivate region-specific AI from the perspectives of education, tourism, and town management.

The Significance of the "Zero Carbon Building" as a Social Experiment Site

──What exactly is the "Zero Carbon Building (ZCB)" you mentioned earlier?

Furuichi: Previously, Zero Energy Buildings (ZEB) were the focus. These buildings achieve net-zero energy consumption during operation through energy-saving technologies and energy generation like solar power, and were widely recognized as environmentally conscious structures. However, with the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050, a new trend has emerged: "Zero Carbon Buildings." These aim for net-zero CO2 emissions not just during operation, but throughout the entire building lifecycle, including procurement, construction, maintenance, and demolition. There is a growing demand for evidence-based architecture that quantitatively assesses CO2 emissions during the design phase and incorporates this data into the building's design. The Taisei Group Next Generation Research Institute has verified this concept and plans to realize Japan's first zero-carbon building in Satte City, Saitama Prefecture, next spring. Looking ahead, we believe an era will come where buildings with reduced CO2 emissions increase in value, tied to carbon pricing. This initiative also connects to our company philosophy: "Creating environments where people thrive = Taisei Corporation."

Sato: Zero-carbon buildings require minimizing CO2 emissions from transporting materials and equipment, necessitating local resource sourcing. We developed a system to circulate resources within the community by collaborating with local timber businesses and companies seeking to reuse waste materials. Building structures consist of vast quantities and an enormous variety of materials. This allows them to function as a "resource bank," storing unused local resources long-term and providing them for future use. This creates a new value for construction: not only reducing CO2 emissions but also contributing to the local circular economy.

──It enhances corporate image, and having an experiential space makes it easier to visualize.

Furuichi: If construction is designed for easy dismantling and maintained over a long span of about 60 years, building materials that have served their purpose can be removed and reused or upcycled into other buildings or furniture. Centered around the physical space of the building, resources are stored and circulated, while the degree of resource circulation and the connections between objects and people are also managed digitally. This makes the circular network visible and easier for local residents to experience. It also allows companies to collect data and participate more easily as a venue for social experiments.

The "Vortex City Project" is conducting a proof-of-concept experiment by building an upcycled cabin. We proposed: "Why not build a frame using recycled wood and aluminum from the local area on a trailer, then integrate upcycled materials from local and participating companies into the roof, walls, and floor?" Companies then participated by contributing their share of the costs. Companies get to test in a real-world setting, while we design the circular building system. Ultimately, everyone can share the results. When the benefits are clear, things move fast.

──Creating a space for social experimentation is key, isn't it?

Sato: For researchers too, having a space for social experiments is incredibly valuable. The places where general contractors' research results are ultimately applied are within cities. Having a space for social experiments and connections with the local community allows us to gain interesting insights and data that can't be obtained solely within a lab. At academic conferences, we can present unique data that others can't replicate.

Furuichi: Engaging in the circular economy also serves as corporate appeal, provides a testing ground for new materials and technologies, and can lead to outcomes like conference presentations and papers. The key is to understand the different KPIs for each participant—sales for some, technology validation for others—and design a roadmap accordingly. If we can effectively align these, I believe the project will gain momentum.

──Providing a platform for companies to bring their own collaborations doesn't seem like a high hurdle.

Furuichi: Virtual platforms alone struggle to foster genuine conversation, and companies are seeking "places to showcase and test research prototypes." By designing a platform that effectively bridges these needs, the result becomes a socially impactful initiative that also creates new business opportunities.

Sato: Actually, when you undertake these kinds of projects, you can address not just environmental issues but social problems too. For example, effectively utilizing materials discarded in large quantities locally or wood from forest management can create jobs in the area and revitalize the community. So, I think it becomes a question of how to create what you might call a community economy.

If you start by saying, "Let's solve this region's disparities and depopulation," it's hard to get things moving. But if you say, "Let's build structures using CO2 reduction technology," companies find it easier to act because it aligns with societal trends and regulatory compliance, and local governments support it with subsidies. Furthermore, local residents are more likely to think, "If the local economy gets revitalized, that benefits us too." By creating a concept where everyone sees the benefits, we can also approach social issues.

Building a solid, profitable business design starting from small economic circles

──People often say, "The circular economy just costs money and isn't profitable." What are your thoughts on that?

Sato: My view is that if money and goods circulate within a region, the circular economy can become economically viable. It might require effort, but by creating a system that "circulates resources within the region and drives the community economy," investments can be reinvested back into the local area. For example, on Ishigaki Island, we're advancing an upcycling project where citizens collect washed-up plastic waste to create products islanders want, using the island's facilities and technology, for use on the island itself. We aim for a circular economy balanced with the local economic scale and waste generation, providing local businesses with ideas and techniques for upcycling larger-scale items like furniture and building materials.

──So, you're saying it's possible to create a functioning economic system within a small, localized cycle.

Sato: Trying to start large-scale operations from the beginning often leads to skyrocketing costs, ultimately making it "unprofitable." Building a community from the smallest possible scale, where people with a connection to the place and the motivation to contribute gather, is more sustainable. Focusing on "creating spaces and items used daily by the people living there" naturally generates demand.

──Hearing your perspective,

- rather than aiming for big results from the start, focus on KPIs tailored to each participant's role, create a roadmap,

- Start small and expand to other areas

- Using CO2 reduction—an area that attracts investment—as an entry point to connect with the local economy

—these insights showed how to translate vision into solid, real-world business. In service design too, starting with small economic spheres seems to unlock many possibilities. I'm excited about the future of business design. Thank you for today.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Furuichi Osamu

Taisei Corporation

Design Headquarters, Advanced Design Office

Senior Researcher, Keio University SFC Research Institute

Beyond regional collaboration and digital twins, he possesses expertise in circular design and zero-carbon architecture, having undertaken numerous domestic and international projects spanning architectural design and system development. His site-specific creations have earned him numerous awards, including the Good Design Award, BCS Award, and SDGs Architecture Award.

Sato Taiki

Taisei Corporation

Technology Center, Innovation Strategy Department

Specializes in the design and research of outdoor and semi-outdoor environments such as cities and stadiums. Recently, research focus has shifted from the laboratory to local communities, engaging in research and development of new approaches through collaborative activities with society, including resource circulation, well-being, smart cities, and autonomous driving.

Tomoyuki Oka

Dentsu Inc.

Sustainability Consulting Office

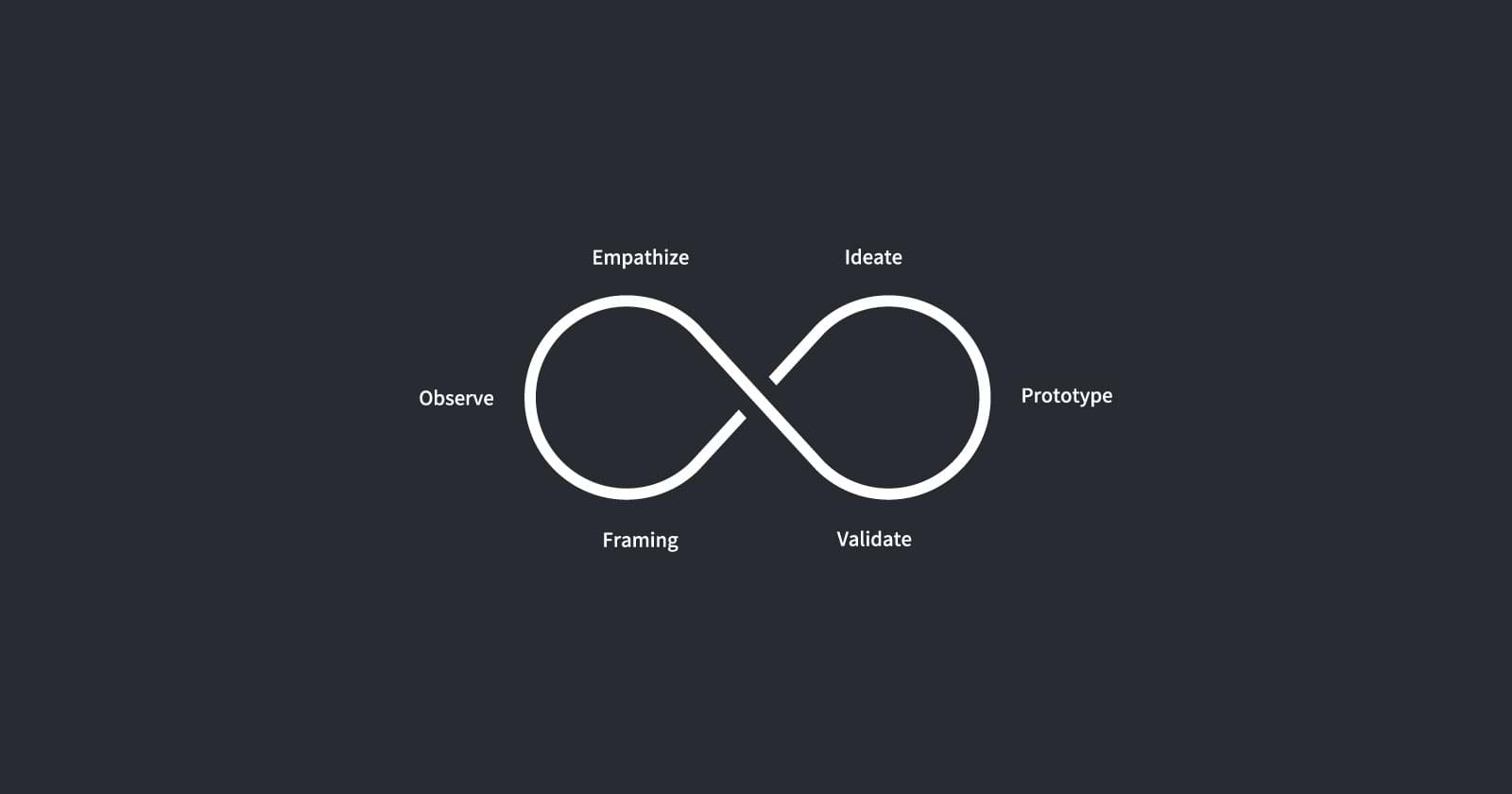

After completing the Graduate School of Media Design at Keio University, he practiced design consulting using design thinking at IBM Japan, Ltd. He has been in his current position since 2019. He works on corporate branding in the sustainability field, supporting new business creation and service design.