How to Tackle Practical and Fundamental Problems

Maruyama: Mr. Aoki, as a retail and distribution analyst, you continue your analysis with both an objective perspective and insight from the corporate field. Thank you for joining us today.

Aoki: Thank you for having me.

Maruyama: The term "omnichannel" is now heard everywhere, but its definition seems to vary slightly depending on each company's situation. In Part 1 of this series, Dentsu Inc. defined omnichannel as "the ability to shop seamlessly, with the same experience anytime, anywhere, across all touchpoints." This means identifying the same customer and providing the same service, regardless of whether they interact through physical stores, mail order, e-commerce, or other channels.

Aoki: Yes, I see it that way too. Simply moving products from physical stores to e-commerce isn't omnichannel. Omnichannel means redefining existing distribution business models using new technology. It also means competing against players with entirely different cost structures. There are many hurdles there.

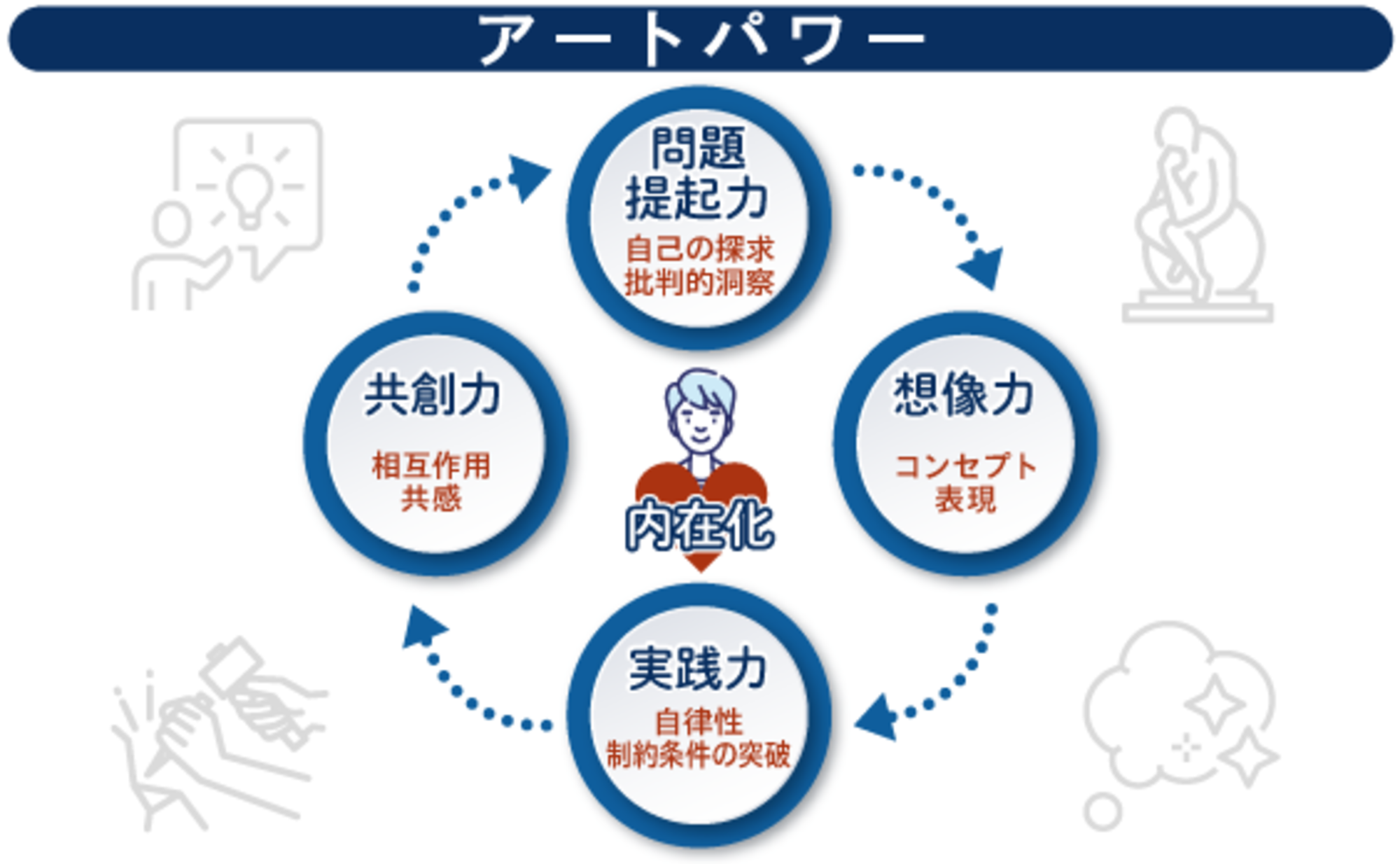

Broadly speaking, the challenges to overcome can be divided into "operational issues" and "fundamental issues." Real-time inventory and customer ID integration fall under the former. Since omnichannel transformation is about building a new business model, the latter involves whether that mindset exists at the top and throughout the entire company, and whether a comprehensive reform of the entire supply chain is possible.

Since we have challenges compiled from actual corporate feedback, shall we proceed based on those?

Maruyama: Yes, please do. In our previous series, we introduced five key challenges.

First: "We can create channels, but we lack people to connect them." Second: "Simultaneously holding the customer's perspective and the management perspective." Third: "Digitizing and systematizing know-how." Fourth: "Ending the battle for customers." And fifth: "Unifying awareness across all channels."

Five Principles for Achieving Omnichannel (Part 1)

1. Create not just channels, but people who connect them

Maruyama: The first challenge mentioned is inter-channel coordination. Earlier, we defined omnichannel as "consistent experiences anytime, anywhere." This essentially means integrating all back-end operations invisible to customers—like physical stores and e-commerce—across channels. This presents a major hurdle.

Historically, companies typically focused on driving sales and building customer relationships by operating separate membership programs and campaigns for each channel. Essentially, they pursued partial optimization within each channel. Consequently, while the concept of "integration being crucial" is understood, the practical challenge lies in determining who will actually take on this role.

Concerns like "If we integrate, won't sales from physical stores flow to e-commerce?" sometimes arise on the ground. It seems quite difficult to assign the coordination role to the people who previously managed each channel.

Aoki: It boils down to the absence of a coordination role. Earlier, I mentioned that "top-level commitment is crucial" as one key point for achieving omnichannel integration. This challenge perfectly aligns with that.

Most companies currently pursuing omnichannel transformation have top management or executives who learned about the situation overseas and raised the banner saying, "We should do this too." However, in the vast majority of cases, they then leave it to the frontline staff to figure it out. Consequently, the frontline, focused on immediate business needs, becomes confused. They also have to maintain their own sales, so it's only natural they can't actively engage in collaboration.

Only top management can bridge this gap. Since this involves sharing inventory and customer IDs to transform existing business models, leadership is absolutely essential.

For that, top management itself needs to study omnichannel. How to leverage IT, how to transform operations. Whether top management has a concrete vision of how this will change the business model significantly impacts the outcome.

Watanabe: Regarding leadership styles, some organizations are firmly led by top management, while others progress through discussions with the field. Which approach is better suited for omnichannel transformation?

Aoki: Collaborating with the front lines is necessary to some extent, allowing top management to understand the field's situation and potential burdens. However, it's essential to maintain a stance of "I'll take responsibility," rather than adopting a completely equal perspective.

Channel conflicts will inevitably arise during the omnichannel transformation process. Only someone standing above each department can resolve them.

Maruyama: We often discuss matters with frontline staff. How should we approach top management from a bottom-up perspective?

Aoki: Ultimately, a shared philosophy is essential. This serves as a value standard to return to when uncertain—a guiding principle, if you will. If you feel your project lacks this philosophy, I believe it's necessary to pause and go through a process of confirmation involving top management.

Earlier, I mentioned the purpose of omnichannel, but there isn't a fixed definition. The ideal form and optimal approach differ by company. Therefore, it's crucial for each company to build consensus on "this is our omnichannel. "

If we're talking about a bottom-up approach, it might be possible to have the frontline teams confirm, "We're doing this to achieve this, right?"

Uehara: Delegating authority to the front lines sounds positive, but when it comes to realizing omnichannel, leaving too much to individual departments won't work well.

Aoki: It might be possible if values were extremely well shared from the start, but it still tends to lead to suboptimal outcomes. People end up acting in ways that benefit their own department or boost their own evaluations.

However, it can't be done by top management alone being enthusiastic. Both establishing a clear core direction and involving everyone around you are necessary. For that, a mindset of thinking together becomes important.

Since it's new, there are risks. On the front lines, people might worry that what they're doing is wrong. Leadership that guides through these uncertainties becomes especially crucial, particularly in large corporations.

2. Holding both the "customer perspective" and the "management perspective" simultaneously

Maruyama: What you just said about top management is also deeply connected to the second challenge. When tackling omnichannel, there's often a recognition that "we should create customer-centric services," but the business perspective is frequently missing.

If you only envision the ideal from the customer's perspective, you might end up with systems that cost a fortune to build or ultimately reduce profits. Both perspectives are necessary, and this is one of the major challenges.

Aoki: The customer perspective versus the management perspective was precisely debated when Amazon went public. Amazon strongly asserts, "We are customer-centric," right? But looking at their actual business model, while it's easy for customers to use, it's also very cleverly designed to generate profits.

There are two key points. First is the cost advantage across the entire supply chain. They minimized intermediate distribution points—typically found between manufacturers' factories or distribution warehouses and customers' homes—beyond their own fulfillment centers. This allowed them to deliver to homes while successfully lowering the overall supply chain cost structure compared to traditional distribution.

The second is cash flow advantage. In the U.S. bookstore distribution industry at the time, inventory turnover rates were only about two times per year, making 180-day payment terms standard. Amazon disrupted this with an inventory turnover rate of ten times per year. The difference between inventory holding periods and payment terms generates cash.

The reason its stock price didn't fall despite prolonged losses after its IPO was that investors recognized this supply chain cost advantage and its strong cash generation capability. While outwardly stating "for the customer (Customer Centric)," it built a meticulous system to sustain the business as the foundation.

Japanese companies probably can't simply copy this approach. While thinking from the customer's perspective from the ground up, they must also naturally consider mechanisms to generate profits. If a company is going to become omnichannel, it must identifywhere its structural advantageslie; otherwise, the very justification for pursuing it becomes questionable.

Uehara: By the way, did Amazon originally proceed with that vision?

Aoki: I believe so. Otherwise, they couldn't have convinced venture capitalists. So, when judging whether a project lacks a management perspective, evaluating it from the viewpoint of whether venture capital would invest might be useful.

Amazon had a solid internal vision for its business structure and then recruited highly professional talent externally to build it. If you rely on external companies for core operational skills, conflicts of interest inevitably arise. Therefore, it's essential to retain the skills critical for creating a profitable system internally. Japan's job roles aren't as clearly defined as in the US, so this might be challenging, but I believe omnichannel transformation should be used as an opportunity to change this.

※In the second part, scheduled for release on August 14, we will continue discussing the five key principles for achieving omnichannel.