The IoT society is no longer a pipe dream; it has become a familiar theme even in the advertising industry. Professor Ken Sakamura of the University of Tokyo is known for envisioning the future of IoT as "computers everywhere" nearly 30 years ago and for building the open computer architecture "TRON." For this achievement, he received the "150th Anniversary Award" this year from the ITU (International Telecommunication Union), the world's oldest international organization.

Yasuharu Sasaki of Dentsu Inc. CDC is the only disciple from Professor Sakamura's lab to join Dentsu Inc. Now, 20 years after joining the company, the society Professor Sakamura envisioned is nearing realization, and his work at Dentsu Inc. is increasingly connected to his roots. We present the first part of a talk show where the two discuss "a world where things connect with each other" from their respective perspectives.

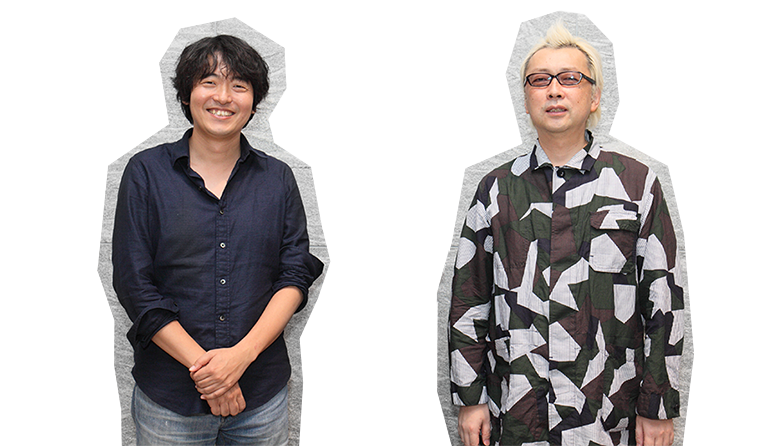

(From left) Mr. Sakamura, Mr. Sasaki

"Just buy some IoT" won't cut it

Sasaki: Today's title is "The New WORLD Created by IoT," but personally, I see it as "The New Dentsu Inc." I hope that by hearing the professor's talk on how IoT relates to advertising agencies, people will think, "Oh, IoT is relevant to my work after all—I need to get on this."

Sakamura: While "IoT" has become a buzzword, it's fundamentally a marketing term. Previously, terms like "pervasive computing" or "ubiquitous computing" were more common, but lately, perhaps for simplicity, "IoT" is used more often. They all mean the same thing. The term "IoT" was coined by someone in marketing at MIT. Essentially, it's just a different word for the same concept as "ubiquitous computing," used for marketing purposes. When things connect to the internet, we can automatically grasp various "situations"—like the number of attendees at an event or the temperature inside a room—without human intervention. Beyond automating production machinery, IoT is a technology that enables optimal control of society as a whole—leading to labor savings, energy efficiency, and reductions in costs like labor expenses.

IoT is currently at the peak of excessive hype. Are you familiar with the "hype cycle," the curve that tracks society's awareness of new technologies? New terms become familiar over time. Even if people don't understand the meaning, they start thinking, "Oh, it must be popular." That's how expectations build.

If services or products using that technology are delivered when expectations peak, a new market opens and grows. But if they aren't delivered in a concrete form, expectations plummet. Soon, people might say, "Oh, IoT? We stopped using it because it didn't generate profits." Research and development takes time. The cycles of marketing and R&D don't perfectly align. To achieve practical implementation, we need patience for the next few years. IoT is fundamentally a concept, so simply saying "Go buy some IoT" won't work. Understanding the underlying philosophy and approach is essential. That's what I want to talk about today.

Originally, I researched embedded computers. The "TRON Project," which I've been involved with for 30 years, focuses on the research and development of real-time OS technology that provides the necessary response at the exact moment it's needed. It's utilized in features like mobile phone functionality and digital cameras' instant autofocus. The project's goal, encapsulated in the term "HFDS" (Highly Functional Distributed System), proposed the concept of all computers within every machine being interconnected via a network. We even published a book on this concept with a German publisher in 1987. This served as evidence, leading to my receiving an award in 2015 from the ITU, given to six individuals worldwide for their contributions to the modern digital society. What I'm getting at is this: it's no exaggeration to say Japan pioneered this field. Yet, we're reacting to IoT as if it were something entirely new.

In 1989, aiming to enrich residential functionality—to make it highly functional—we created the "TRON House," where every part of the home was controlled by computers. This is what we now call a smart house. The idea of a smart house, where things connect to the internet, seems convenient and easy to grasp, right? Then there's transportation. Systems to reduce traffic congestion, landslide sensor detection, streamlining logistics, food traceability, and so on.

It takes 20 to 30 years for science and technology to become practical. Smart houses are only just now starting to be commercialized. In 2004, aiming for sustainability—meaning eco-friendliness—we created the super-intelligent house "PAPI" with Toyota. In 2017, we plan to announce the next model with the LIXIL Group. While the technological concept remains IoT-based, the target objective will introduce a third keyword—neither eco nor rich—which I cannot disclose now. It will emerge with a significantly altered concept.

From "Closed IoT" to "Open IoT"

Sakamura: IoT research itself has advanced considerably, and we understand what needs to be done and how. The remaining challenges are cost reduction and how to bring it to market. The internet is interesting because everyone uses it, creating a virtual world. IoT technology, if closed, is already being put to practical use within companies and such. However, it cannot remain closed. We cannot transform society unless we move from closed IoT to open IoT. Japan has advanced in networking, but it often remains confined to closed networks, like connecting companies within a group. Globally, there's now a movement to network all parts manufacturers worldwide.

This trend is gradually influencing other industries. For example, with online printing services, you can order printing with your desired delivery date and price, and the printed materials arrive from a printing company you've never met, without any prior consultation. With this method, the quality might be equivalent to before or perhaps slightly lower. However, quality will gradually improve. The biggest change is in cost; opening up to the world lowers costs.

Japanese semiconductor manufacturers missed this wave. While highly capable, they kept both design and production confined within their own group. The world is shifting towards a model that separates technology development, manufacturing, and sales. This is what we call "Open IoT."

The Olympics represent a concrete advancement in Open IoT initiatives. I am currently working on creating a system that supports hospitality through ICT technology. By 2020, over ten times the current number of visitors will come to Japan. The biggest challenge for these visitors will likely be navigating complex urban transportation. The "Hospitality Cloud" currently under development is a project aiming to solve this problem by connecting transportation IC cards to the internet.

Discussions are currently underway with hotels, retailers, cultural facilities, restaurants, transportation operators, financial institutions, hospitals, and others. For example, imagine a scenario where information about a restaurant recommended by a hotel concierge is sent to an Omotenashi Card. This card could then automatically coordinate various services: telling a taxi the destination via GPS, or having the recommended menu items served at the restaurant. That's the future we envision. Current transit IC cards serve only to board trains and function as small change, but IoT aims to enhance their capabilities.