Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

What are the key points for recruiting highly skilled IT talent, as discussed by two genius programmers?

Takuya Akiba

Preferred Networks, Inc.

Naohiro Takahashi

AtCoder Inc.

Preferred Networks is one of Japan's few unlisted venture companies valued at over $1 billion—a "unicorn company." It stands out as a unique enterprise where 80% of its approximately 280 employees are engineers and researchers, many of whom are world-class top programmers.

This time, we have arranged a conversation between Naohiro Takahashi, CEO of AtCoder, which hosts competitive programming contests, and Takuya Akiba, Executive Officer at Preferred Networks. They discuss the state of hiring highly skilled IT talent and what is necessary for talent development. Both born in 1988 and former programming prodigies, their conversation was highly engaging.

Demonstrating Capabilities in the Most Competitive AI Field to Contribute to Solving Social Issues

Takahashi: I was passionate about competitive programming during my student days, which later led me to launch AtCoder. How did you end up at Preferred Networks (PFN)?

Akiba: I started participating in programming contests around ninth or tenth grade and, like Takahashi, became deeply engrossed in competitive programming. Eventually, I found the algorithms themselves fascinating. I immersed myself in algorithm research from university through my doctoral program and decided to continue studying algorithms at the National Institute of Informatics (※1), intending to become an algorithm specialist. However, as I continued my research, I began wanting to use the skills I had cultivated to solve societal problems and create value.

When I considered where I could truly compete using my technical skills, the field of AI seemed ideal. AI is the most fiercely competitive domain, with intense development races against world-leading companies like Google, and deep learning (※2) technology evolving daily. I believed that fully leveraging my technical abilities in this world could also contribute to solving societal challenges, which led me to join PFN.

※1 = National Institute of Informatics

Japan's only comprehensive academic research institute for informatics. It promotes integrated research and development in information-related fields such as networks, software, and content. It also collaborates with universities, research institutions, and private companies nationwide to build and provide cutting-edge academic information infrastructure like CSI.

※2=Deep Learning

A technology enabling machines to automatically extract features and patterns from large datasets. Deep learning, in particular, has dramatically improved accuracy in specific tasks like image and speech recognition, driving the rapid evolution of AI-related technologies.

Takahashi: In my case, I enjoy the thrill of competing in the world of competitive programming, while Akiba-san thrives on competition within the business world. Our fields may differ, but perhaps the core is similar.

Akiba: Exactly. Even after joining the company, I actively pursue projects that create value by winning competitions. For instance, we've set world records in deep learning training speed that made headlines, and achieved second place globally in image recognition contests. We're building valuable technology for the company while continuously challenging the world.

Takahashi: There are many AtCoder users within PFN itself, right?

Akiba: At PFN, about 80% of our 280 employees are engineers and researchers. I believe over 20 have experience in competitive programming, including AtCoder. Some might participate discreetly for study purposes without publicly announcing it. Our president, Toru Nishikawa, is also a former participant in the ICPC (International Collegiate Programming Contest) world finals. When I chose PFN, the opportunity to work alongside people with world-class programming skills was a major factor.

Takahashi: In what fields do PFN engineers primarily excel?

Akiba: PFN aims to commercialize cutting-edge technologies and drive innovation across various real-world fields. These span autonomous driving, robotics, bio, chemical, factory optimization, and more, with deep learning as the core technology. We have engineers developing foundational deep learning technologies and models, robot engineers, and engineers focused on productization and service development.

Using objective metrics to prevent mismatches in talent recruitment

Takahashi: I often hear that non-IT companies struggle with hiring engineers. Common reasons include HR staff lacking programming knowledge and the difficulty of visualizing skills. PFN provides coding tests we've developed (tests where candidates write actual programs to solve given problems) for engineer recruitment. How do you utilize them?

Akiba: Candidates solve coding test problems before interviews, and we base the interviews on those results. After that, like other companies, they go through several interviews before reaching the executive interview stage.

Takahashi: What do you ask during the interviews?

Akiba: We have a dialogue using the code they wrote in the coding test as a starting point. At this stage, we don't just look at whether they got the "correct answer." When programming for a given task, there are various approaches, right? If there's a part where you think, "Why did they write it this way here?", we want to know if they wrote it that way after careful consideration or if they simply couldn't think of anything else. Digging into that "intent" during the interview helps us understand their thought process and depth of knowledge, making it a major point in assessing their skills.

Takahashi: When evaluating, which carries more weight: "implementation skills" or "algorithm ability"?

Akiba: Rather than one over the other, we're looking at more fundamental programming ability. In tests, we assess the ability to correctly write short routines that handle complex processing.

Of course, we also look at algorithmic ability, but rather than focusing on "solving difficult problems," we're more interested in "designing algorithms for ordinary problems." For example, whether they are mindful of computational complexity (※3).

※3 = Computational Complexity

A metric for evaluating algorithm performance. It consists of two indicators: the number of processing steps (time complexity) required for the algorithm to solve a problem, and the amount of computer memory (space complexity) needed to run the algorithm. Algorithms with smaller computational complexity are considered more efficient.

Takahashi: AtCoder provides programming test questions to companies other than PFN, but we actually tailor the content depending on the client. For companies like PFN, where engineers review the code itself and use it as interview material, we can include trick questions because they thoroughly examine the code even for incorrect answers. However, for companies where HR personnel, who may not understand the code, evaluate based solely on scores, we create problems that as accurately reflect the candidate's true ability as possible.

Regardless, the fundamental philosophy remains unchanged: "AtCoder tests assess algorithm design and implementation skills." When evaluating design skills, we focus on computational complexity improvements. However, problems that are overly mathematical or too distant from the practical implementation skills required in real-world programming can lead to a mismatch with the talent companies seek. Therefore, we consciously design problems to assess implementation skills as much as possible.

Akiba: Of course, coding tests only reveal one facet of a candidate's abilities. Some with high scores aren't hired, and vice versa. Still, ratings from programming contests are highly objective indicators. They accurately reflect algorithmic ability and the skill to implement short routines.

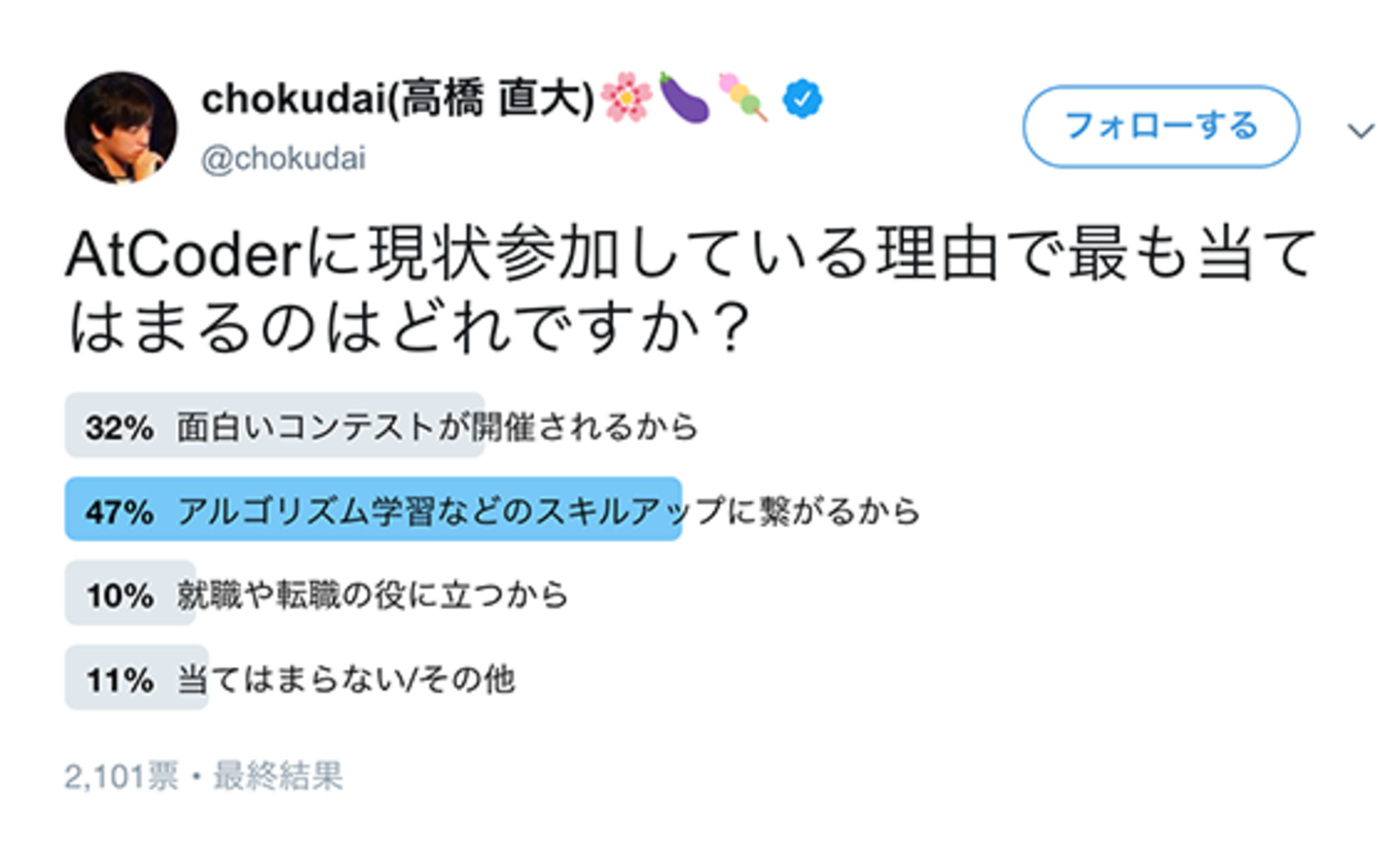

Takahashi: AtCoder launched the "Algorithm Practical Skills Certification" in December 2019. As mentioned earlier, very few companies examine the intent behind code during engineer hiring. Most lack methods to assess programming skills, leading to hiring mismatches. That's why we started this certification service—to evaluate practical programming abilities in real-world scenarios. What are your thoughts on this certification, Akiba-san?

Akiba: I think it's a wonderful initiative that will be useful for many companies. I expect it will become an objective metric, similar to AtCoder's ratings system.

Takahashi: Thank you. While this certification alone cannot measure all the skills needed for real-world work, I believe the correlation is strong enough.

I also placed in the top five at NASA's programming contest, and my algorithm was used in Space Shuttle technology. Cases where programming contests lead to real-world applications are not uncommon. AtCoder also hosts multiple contests focused on solving real-world industry challenges. While there is a gap between competitive programming and real-world work, it's not as if the two are completely disconnected.

Akiba: I believe the skills cultivated through competitive programming can be greatly applied in real-world business. The most prominent of these is the ability to implement quickly and accurately. Deep learning isn't just about implementation; it's a continuous cycle of trial and error. You read papers, implement them... repeating this process many times. If you can cycle through this process quickly and accurately, you'll ultimately arrive at a superior model. In that sense, competitive programming skills will be useful in all kinds of situations.

The Key to Programming Education Lies in "Competition"

Takahashi: Starting in the 2020 academic year, programming education becomes mandatory in elementary schools. In my case, I honed my skills by relentlessly competing in programming contests. Having talented peers around me was incredibly valuable. How did you develop your programming skills, Akiba-san?

Akiba: When I started programming in junior high and high school, self-study was my only option. I was lucky enough to join a club where seniors taught me, and from there I read books and made my own games. But initially, I couldn't learn deeply enough and wasn't truly hooked. Later, seeing outstanding competitors and meeting rivals at contests made me feel my abilities skyrocketed.

Takahashi: It really shows that learning in an environment with people you compete and collaborate with helps your skills grow. Thinking about it that way, I believe it's valid to encourage competition in programming skills within the school education system too.

Akiba: I've taught programming classes at Tokyo University, and you also have opportunities to teach programming, Takahashi. What kind of teaching approach do you take?

Takahashi: When teaching programming to large groups, I assume everyone has already read the textbook cover-to-cover. So, I start by having them solve practical problems right away. Since they can read the book on their own, it's pointless for me to teach the textbook content step-by-step. This approach lets me focus on the key points I need to teach, making it more efficient.

Akiba: That's pretty Spartan. But I have a similar approach (laughs). My goal when teaching wasn't "to make sure everyone understands," but "to get even one more person genuinely hooked." I introduced competitive programming problems, talked about "what makes good code," and sprinkled interesting points throughout the class while incorporating advanced topics.

That's because I myself grew the most when I discovered something I could get truly absorbed in. Programming is a field where experience is crucial, and I believe immersing yourself and relentlessly accumulating experience is the best path to growth.

Takahashi: In that sense, it might be difficult for students who aren't interested to keep up with the class.

Akiba: That's true. So, for elementary schools starting classes soon, I'd be happy if teachers could work hard to spark their interest. Visual programming languages (※4) have advanced recently, creating a great environment for learning programming. We didn't have such well-prepared learning environments back then, so I envy today's elementary students.

※4 = Visual Programming Language

Instead of writing programs in text, these languages use graphical components representing necessary program elements, allowing programming through operations like drag-and-drop. Examples include "Scratch" developed by the MIT Media Lab and "Programmin" developed by Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

Takahashi: But our era had its good points too, right? Back then, commercially available games weren't that high quality, so you could make games yourself that were on par with the commercial products. But that's absolutely impossible now. In other words, while the barrier to creating something good has lowered, it's become an era where it's difficult for a single person to create something, release it to the world, and get a response. It might be hard to hone programming skills motivated purely by "creating things."

That's precisely why I think using "competition" as motivation is a good idea. In fact, I hear all the members of my alma mater's computer club are doing competitive programming.

Akiba: Whether it's the Olympiad in Informatics or the Algorithm Practical Skills Certification, having a goal creates a momentum where everyone strives together, increasing the number of programmers. I hope such opportunities grow. While contest results aren't everything, becoming engrossed in competitions can positively impact one's future career and life.

Takahashi: Assuming we increase the number of highly skilled IT professionals this way, what do you think is needed to expand their opportunities?

Akiba: Perhaps deepening the understanding of technology among corporate management?

Takahashi: That's certainly true. Despite the growing demand and ongoing shortage of highly skilled IT professionals, only a fraction of companies are actually increasing their compensation. Many companies seek engineers, yet some still recruit them under general management positions. There are also challenges in hiring practices, and even after joining, there might be no dedicated technical departments. While it's important for us to work on increasing the number of highly skilled IT professionals, I also think that unless companies establish systems to properly accept and utilize excellent engineers, the opportunities for them to thrive won't increase.

Akiba: You're absolutely right. To add to Takahashi-san's point, I think it's also crucial whether companies can offer work that engineers find interesting. That was one reason I decided to join PFN. Companies that make engineers think, "There's interesting work here," "This is technically challenging and seems like it could create new value," or "Pushing this technology to its limits might solve social issues" are naturally attractive to engineers.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Takuya Akiba

Preferred Networks, Inc.

Executive Officer, Vice President of Machine Learning Infrastructure

Ph.D. (Information Science and Engineering). Completed the doctoral program at the Graduate School of Information Science and Engineering, University of Tokyo in 2015. After serving as an Assistant Professor at the National Institute of Informatics, he joined Preferred Networks, Inc. as a Researcher in 2016 and has held his current position since 2018. He is engaged in the research and development of deep learning frameworks, primarily focused on accelerating and scaling deep learning. Co-author of the book Programming Contest Challenge Book. Contributor to the book Algorithms and Data Structures for Programming Contest Strategy. Reviewer for the book 150 Problems to Train Your Programming Skills for Global Competition.

Naohiro Takahashi

AtCoder Inc.

President and CEO

Placed third globally in the Imagine Cup programming contest hosted by Microsoft. Subsequently achieved numerous top results in programming contests, including four wins at the ICFP Contest and two runner-up finishes at TopCoder Open. In 2012, founded the service "AtCoder" to host programming contests in Japan. It has since grown into a contest attracting over 7,000 participants weekly.