My senior colleague and neighbor, Mr. Shunji Okuyama, kindly gifts me delicious seasonal delicacies from Akita every season. Just the other day, he gave me a large amount of wild mountain vegetables, saying, "My brother went into the mountains and picked these for you."

The staples like aiko, koshiabura, and kogomi (the red-stemmed variety is apparently rare) were there, of course, along with hideko (often called mountain asparagus) and honna, which has a delightful bitterness like seri. The vivid green color is stunning, and the crisp, crunchy, and slippery textures are irresistible. It's a flavor that energizes you from the core. I can't even imagine early summer without wild mountain vegetables; it would feel so lonely.

By the way, when writing about "ideas" or "concepts" like in this column, I tend to treat "logical thinking" as if it were the enemy. In fact, one day over ten years after joining the company, I read the first 78 pages of the Discourse on Method (correctly titled Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One's Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences [Discourse]). Incidentally, it's the first 78 pages of that book, apparently (lol). While I understood Descartes' frustration with the academic world dominated by theology at the time, I couldn't help thinking, "Ah, it's all your fault this world has become so boring!!"

Incidentally, Descartes' methodology, which became the foundation of logical thinking, is like this:

***

First, I resolved to accept nothing as true unless I clearly recognized it as such. In other words, to carefully avoid hasty judgments and prejudices, and to include in my judgment only what appeared to my mind with such clarity and distinctness that there was no room for doubt.

Second, to divide each difficult problem I examine into as many small parts as possible, and as many as are necessary to solve it better.

Third, to guide my thoughts in an orderly manner, starting with the simplest and most easily recognized things, and gradually ascending step by step to the recognition of the most complex things, even assuming an order among things that naturally have no inherent sequence.

Finally, in every case, to make a complete enumeration and a thorough review, to be certain that nothing has been overlooked.

(Excerpted from the Iwanami Bunko edition of "Discourse on Method" by Descartes, translated by Takako Tanigawa, pp. 28-29)

***

It's very "correct," but somehow cold and critical, isn't it? You might feel like interjecting, "There's nothing in this world so clear that there's absolutely no room for doubt!" That said, it's not that "logic" is unnecessary for generating ideas or concepts.

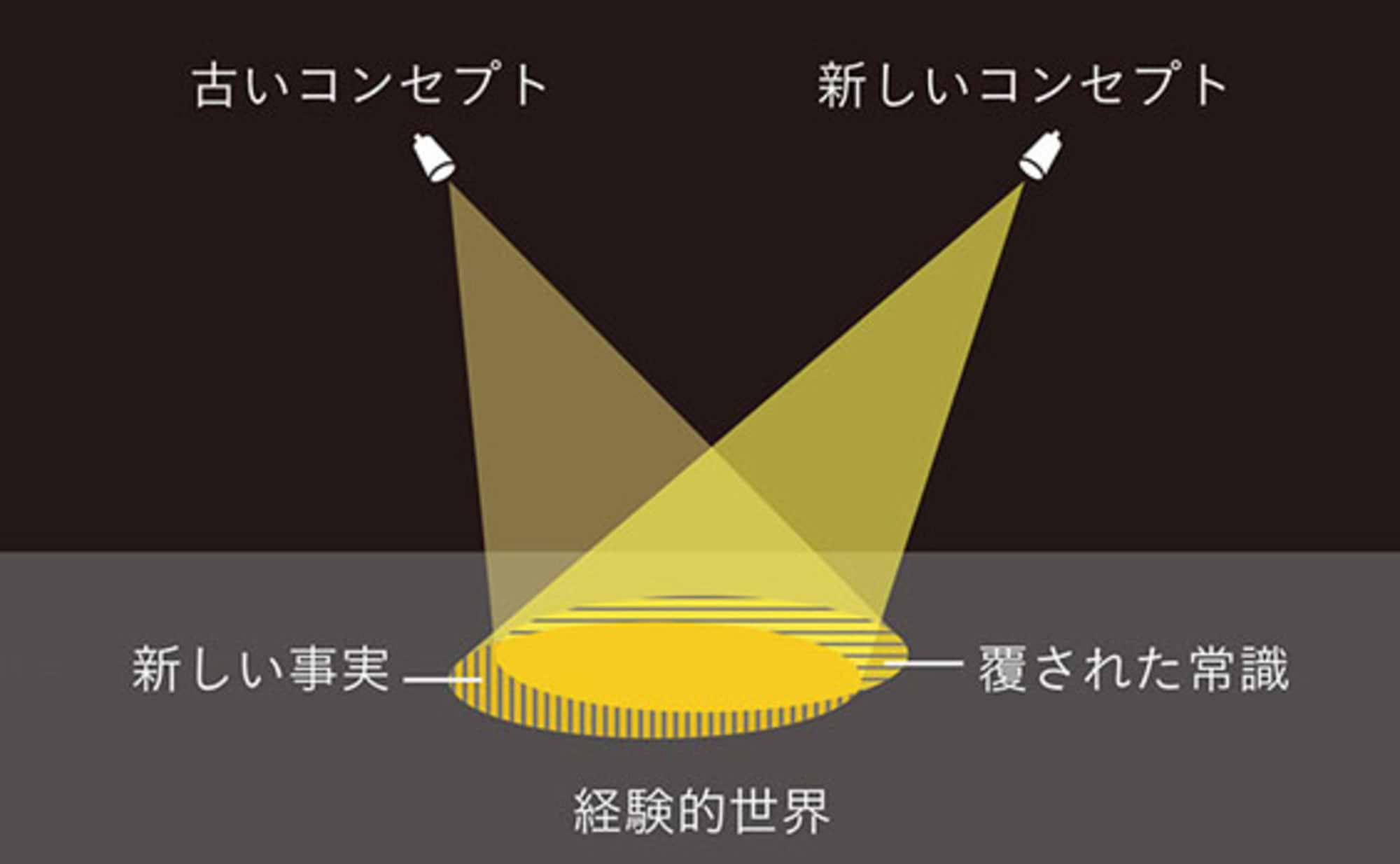

To spark innovation, two interactions are essential. One is the back-and-forth between the "target" and the "product/service." This involves raw, sensory engagement with people's true feelings to shift their mindset and connect it to the product/service.

The other is the back-and-forth between an organization's or individual's "vision" and "concrete measures (reality)". A concept must not be a mere "whim"; it must "solve problems to realize the vision". "Logic" is needed to check whether the acquired "new perspective" actually works.

Cross Frame

In my previous book, The Idea Handbook, and in this column, I've only used the four vertical boxes as a framework for organizing "spontaneous ideas." However, when writing How to Create Concepts, I evolved it into a "cross frame" that includes four horizontal boxes to explain the entire concept (idea) creation process in a single diagram. As this shows, ideation requires not only free-flowing, scattered thoughts but also cool, objective logic.

Whether it's the thrill of foraging wild plants or the hands-on experience of concept creation, conveying physical sensations is quite challenging. I'll continue refining my approach bit by bit, so I hope you'll stick with me.

Please, enjoy!