Believing the saying "There's no such thing as bad udon in Kagawa," I was first taken to a certain long-established shop famous for "zaru udon." The moment I put the noodles in my mouth, "Huh? Soggy??" As I desperately finished eating this seemingly lifeless mass, I realized the obvious truth: even in the birthplace, good shops are good, and bad shops are bad.

Since then, I've visited countless shops and eaten countless bowls. But I've also learned that even at the same shop, the taste varies significantly depending on the season, timing, or even my physical condition. Sanuki udon is fundamentally a laid-back food culture rooted in daily life. I holed up in Takamatsu again this Golden Week, but I didn't go on any "udon pilgrimage." Instead, I just went to my regular spot every day, slurping noodles with the mindset that finding a bowl that truly hit my taste buds would be pure luck.

Incidentally, my absolute favorite type is the "springy" kind. More than just a "chewy" texture, it has a firmness that feels like it might snap, dancing lustrously in your mouth with a "slurp." If it's too "plump and dense," it feels a bit heavy. I prefer it on the firmer side, but I dislike it when it's overly "rock-hard." Somewhere between that, a gentle, plump udon makes me happy.

Spinning Thoughts

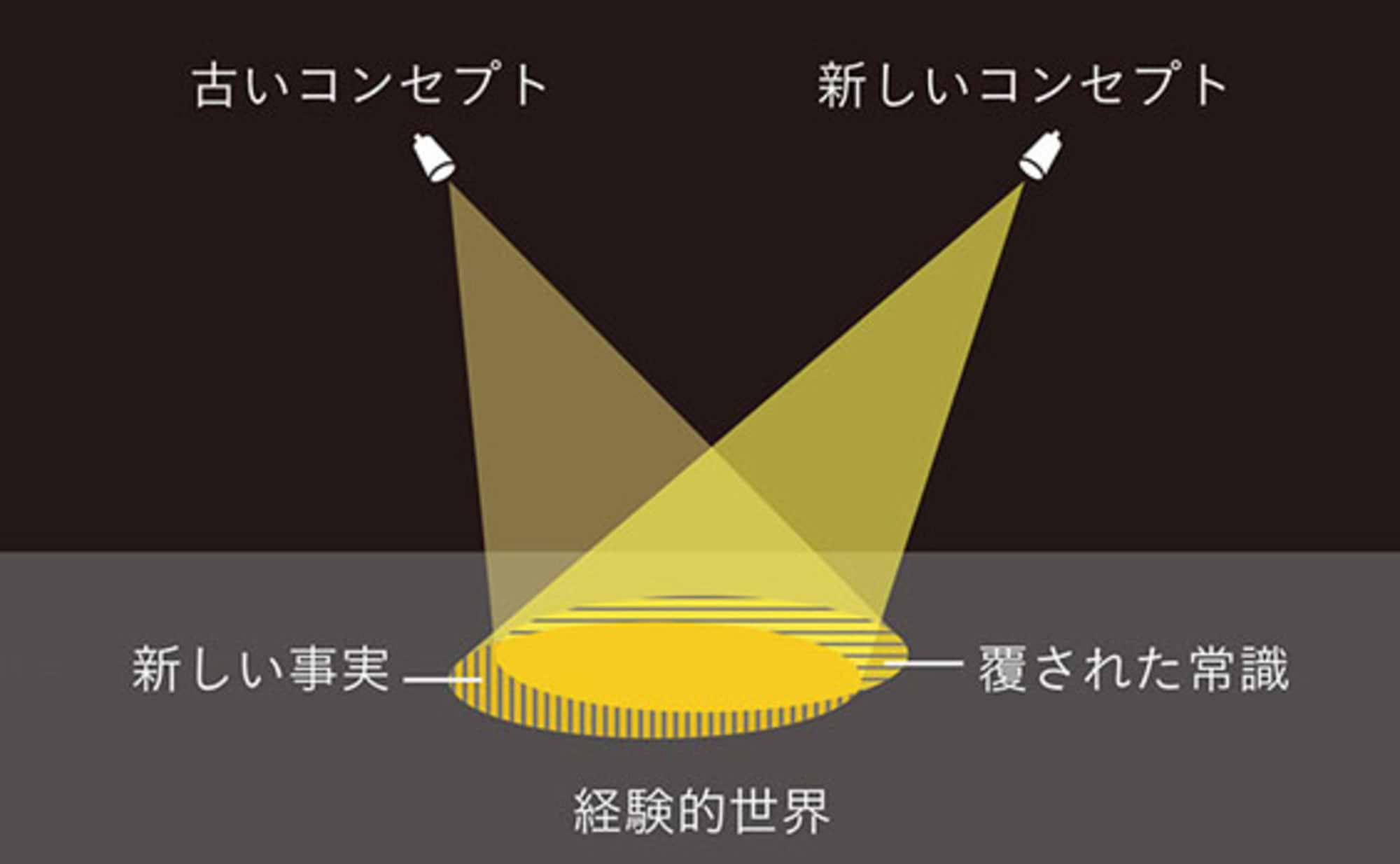

Now then. To generate a concept, you need the four modes represented by circular thinking. And its climax is the "Discovery! Mode" – verbalizing that physical sensation (intuition) of "Hey, why not try this!?" This process is essential to elevate it from a mere "idea" to a "new perspective for solving problems toward a goal."

Thinking about it this way, Japanese—a language that can directly verbalize physical sensations like "plump and juicy" or "chewy and sticky"—seems quite a creative language.

What's even more interesting about Japanese is that when existing expressions like "slippery" or "chewy" feel inadequate, you can freely create new words based on your own sensations. Saying "slippery-slippery" instead of "slippery" suggests something quite juicy, while "gooey-gooey" evokes something softened and melting. English does have onomatopoeia like "bowwow" for dogs or "cock-a-doodle-doo" for roosters, but these often feel childish and unsuitable for business contexts. The variety is limited, and they aren't actively created in large numbers.

On the other hand, Japanese's tendency to convey physical sensations (intuition) too easily has its drawbacks. It means you can vaguely grasp what the other person is thinking, like "Isn't this how we should do it!?", and that often leads to stopping your own thinking, assuming that's sufficient.

As I've repeatedly mentioned in this series, only by using metaphors to express concepts and ideas in simple words can we logically evaluate their value. Even Taro Okamoto's masterpiece concept, "Art is an explosion," could be shared sensually among Japanese people with the same cultural background—something like, "You know, like, that kind of feeling." But that's only a temporary resonance. It was precisely because Taro Okamoto studied philosophy at the University of Paris that he could develop words capable of sharing that feeling across time and space, without relying on such fleeting resonance.

I don't think Japanese people are bad at creating ideas or concepts; it's just that we have a weak habit of finally capturing them in words.

Um. Another charm of Sanuki udon is its tempura. The now nationally famous "soft-boiled egg tempura" originated in Takamatsu City, and they even deep-fry dried tofu soaked in rich broth. It's delicious, but... it makes you fat.

I'm sending this manuscript back to Tokyo with a sense of urgency—I need to get my weight back down quickly!

Please, enjoy!