From left: Dentsu Inc.'s Makoto Sasagawa, JAXA Kakuda Space Center Director Makoto Yoshida, IST Founder Takafumi Horie, IST President and CEO Takahiro Inagawa

Space business encompasses diverse activities: satellite launches, transporting personnel and supplies to space stations, lunar exploration, and more. The essential infrastructure underpinning all this is the rocket.

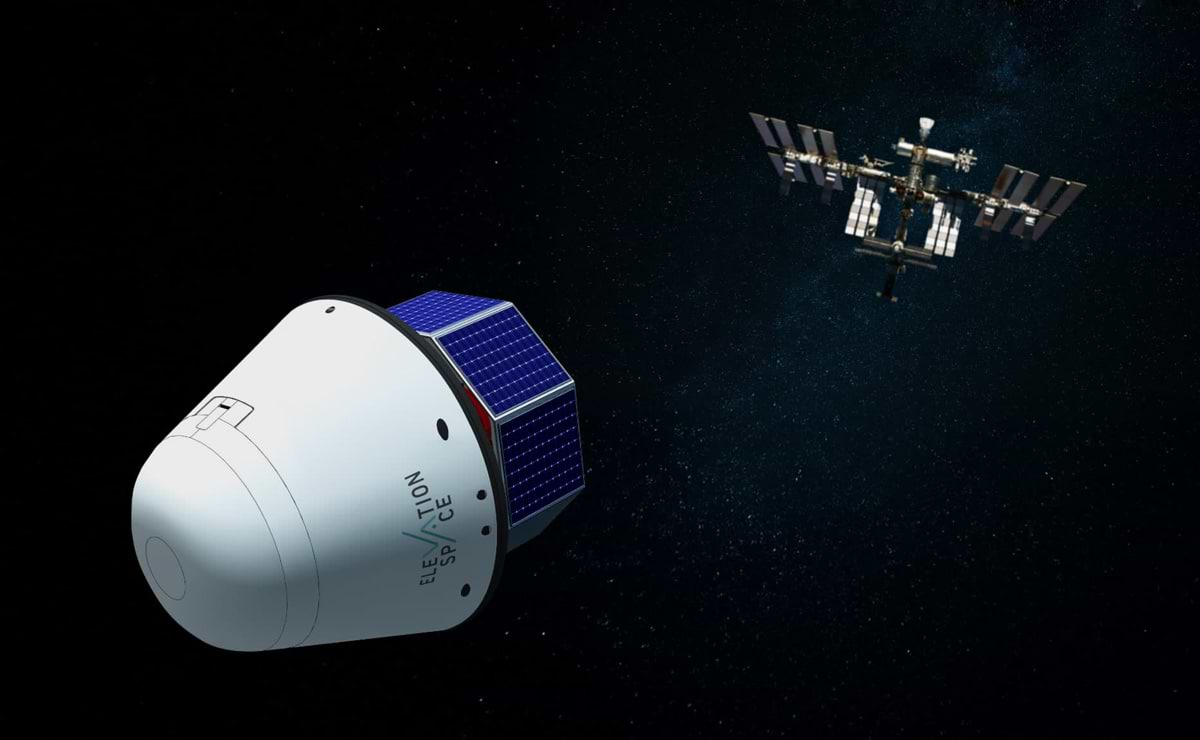

Interstellar Technologies (IST) achieved Japan's first private rocket to reach space. To support the development of IST's satellite rocket "ZERO," the corporate partner organization "Everyone's Rocket Partners" was formed. Among its partners, JAXA's (Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency) technical support became a notable topic.

We visited Makoto Yoshida, Director of JAXA's Kakuda Space Center, and spoke with Takafumi Horie and Takahiro Inagawa of IST about the significance of their partnership and the future of Japan's space business. (Interviewer: Makoto Sasagawa, Dentsu Inc.)

After the Successful Launch of the MOMO-3 Observation Rocket

Sasagawa: Congratulations on the successful launch of MOMO-3.

Horie: Honestly, the excitement of the launch was overshadowed by the thought, "We need to raise money immediately!" We'd been scraping by the whole time. Even if Unit 3 had failed, we could have survived for about a year, but facing the next launch under that kind of pressure would have been mentally unbearable.

Sasagawa: The failure of the second rocket was tough, wasn't it?

Horie: Yeah, that one. We burned it all the way to the launch pad. Anyway, it was all about "We have to keep the company going" and "We have to hold out until the next launch." We went to our existing investors saying, "Sorry! We need more funding!" and they reluctantly invested, saying "Well, what can we do?" Back then, we had zero funds and zero margin for developing the next ZERO. But MOMO's success gave us a clear path for ZERO development, allowed us to build a factory, and enabled us to hire people.

Sasagawa: And then we raised 1.22 billion yen in Series B funding.

Horie: It was truly a relief. However, we still need about 4 billion yen total to reach ZERO's launch in 2023. Everyone, we appreciate your continued support!

Sasagawa: Mr. Inagawa, what changes have you seen?

Inagawa: The biggest change is in our structure. Before, we could barely allocate resources to ZERO development, but now about half our staff can work on it.

Sasagawa: How did the success of Unit 3 strike Director Yoshida?

Yoshida: It further strengthened my resolve that we must cooperate more seriously. We are rocket engine specialists and thoroughly understand the core technologies, but we've never experienced the entire process from development to launch. IST has achieved that. Successfully launching it into space is proof that their technology has reached a high level across the board. IST engineers are already stationed here at the JAXA Kakuda Space Center. If they can effectively utilize the results of our joint creation, I believe we can develop an excellent satellite launch vehicle, ZERO.

Inagawa: I'm glad to hear you say that. While we still have room to grow in each individual area, I take pride in the fact that having experienced the entire process is IST's strength.

Horie: By the way, how many people are working here (at the Kakuda Space Center)?

Yoshida: We have just under 50 researchers. Including partner companies and test support staff, the total is around 170 people.

Horie: How much of the rocket engine development is done at Kakuda?

Yoshida: We handle the initial stages of rocket engine development, conducting component tests on things like nozzles and bearings. Currently, we're testing engines for the H3 rocket (※1). The "selling point" of the Kakuda Space Center is that it allows testing under conditions identical to space.

※1 H3 Rocket

JAXA's next-generation core rocket. Its first launch is scheduled for fiscal year 2020. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries has been actively involved since the development phase, aiming to achieve low-cost launches through the use of commercial off-the-shelf components.

The turbopump is an essential component for IST's next target, the orbital injection rocket "ZERO." The photo shows a turbopump developed by JAXA engineers for research into low-cost rocket technology. The test data from this is planned to be shared with IST through co-creation activities.

Yoshida: This is the turbo pump (※2) developed by JAXA for research into low-cost rocket technology. It's fresh off the assembly line, just before testing. It looks more like a sea urchin than a sea cucumber (laughs). The data obtained from testing this turbo pump will be shared with IST through our co-creation activities.

※2 Turbo pump

A component installed in liquid rocket engines. Its role is to use a turbine to feed hydrogen and oxygen fuel from the fuel tanks to the rocket's combustor.

Inagawa: I'd seen it on drawings, but this is my first time seeing the actual thing too.

Yoshida: And in this co-creation activity, we're also testing injectors. We've started testing newly designed injectors, and we're gathering data that will be useful for JAXA too. The injector is the part that sprays out the fuel; it's a very important component for stable engine operation.

Inagawa: Its role is to inject the rocket's propellant into the engine and mix it. Experiments conducted at the Kakuda Space Center are enabling us to develop low-cost, high-efficiency injectors. JAXA's existing technology and IST's experience are truly converging.

Testing of the injector, developed with the goal of low cost and high efficiency, is also being conducted at the Kakuda Space Center.

An era where JAXA supports private companies' space challenges

Sasagawa: Has there been interaction between IST and JAXA for some time?

Inagawa: We've been meeting at academic conferences and presentations for a long time, haven't we?

Yoshida: Even back in the H3 rocket era, there was discussion that "private companies should take the lead in development going forward." Around 2011, we started research on engines that were low-cost, reasonably high-performance, compact, and lightweight. Against that backdrop, there were JAXA researchers at the time who had personal connections with IST.

Horie: Mr. Tetsuo Hiraiwa, right? Going back even further, JAXA's Atsushi Noda was also involved with IST's predecessor, the "Natsu Rocket Group." He was building satellites, and around 2005, he kept saying, "The era of ultra-small satellites is definitely coming." Back then, we had quite a few debates like, "Is that really going to happen?" and "Don't we need to build bigger rockets?" (laughs).

Sasagawa: So IST was already focused on small rockets back in 2005!

Horie: It wasn't so much a choice as we had to start small due to funding constraints. Back then, we were genuinely unsure if there was real demand for small rockets. It was like, "Are you sure about this, Noda-san?" (laughs).

Sasagawa: So personal exchanges started around 2005?

Inagawa: As an organization, I think it was around 2015. We signed a contract with JAXA for consulting on liquid rocket engine test facilities. Of course, the rocket engine itself is the main focus, so we wanted to collaborate on that.

Yoshida: We had our own internal struggles. As JAXA, we weren't sure back then how much technology we could share with private companies. The fact we could move the conversation to "co-creation" was thanks to JAXA's new research and development program, "J-SPARC," launched last year. JAXA's role became clearer – "to conduct R&D with private business as the end goal" – making it easier for us to move forward.

Horie: Having a framework really helps, doesn't it?

ZERO's corporate partner organization, "Everyone's Rocket Partners." Launched in March 2019, it later saw the successful launch experiment of MOMO No. 3.

Inagawa: Previously, we were told about the content of published papers, but now we can create things together. The hardware is already this far along, and the experiments are complete. Being able to work together while looking at the actual target right in front of us is truly significant.

Sasagawa: Has the collaboration with IST brought any changes to the JAXA side?

Yoshida: Our preconceptions get shattered daily (laughs).

Inagawa: When we consulted them about aiming for a certain cost level, they responded, "Hmm. That's one more zero than before" (laughs).

Yoshida: But we also have a mission to spread the space technology we've accumulated to the private sector. Plus, new technologies are emerging constantly even in the general market now. So, we're challenging ourselves to explore new ways of building, wondering if it might actually be possible to do it at a lower cost than our conventional wisdom suggests.

Sasagawa: It's like JAXA, which has a culture of building top-tier products like Ferraris, suddenly taking on low-cost development. Did everyone smoothly shift their mindset?

Yoshida: It might not be complete yet. There's a fixed perception about space, and since we're on the extension of the technology we've built up until now, it's very difficult to judge which parts of the conventional approach we should break away from.

Horie: When developing rockets, there are points where you think, "Why is this even necessary?" about traditionally used methods, but actually, there's often a solid reason behind them.

Yoshida: Exactly. Even we experts struggle to tell if something was just done by chance or is genuinely necessary. That's why we need to test repeatedly under slightly different conditions. Sometimes, while doing that, we've accidentally stepped away from dangerous points. The challenge of trying new construction methods is that high, but so far, everyone's been enjoying it (laughs). The ZERO project is rewarding because we actually have a launch opportunity.

Sasagawa: Collaborating with IST is a challenge for JAXA too, isn't it? Compared to MOMO's development, how much more difficult is ZERO's?

Horie: The rocket engine is the toughest part, no question.

Yoshida: What's actually needed to launch a satellite isn't altitude, but velocity. Observation rockets like MOMO reach high altitudes, but their velocity is zero at apogee. But with satellite launchers like ZERO, you need a velocity of about 8 kilometers per second for it to be a satellite launch vehicle. That means the engine has to work that much harder.

Inagawa: The completely new parts for ZERO are the injector and the turbopump. But honestly, there's virtually no one who really understands turbopumps. Among those few, the only place we could access in Japan—no, the only place in the world—was right here in Kakuda.

Yoshida: Thank you (laughs).

Competing Globally! The Strengths of Japan's IST

Sasagawa: In the small rocket satellite transport business, companies like America's Rocket Lab are leading the way. Compared to such rivals, what strengths does IST have?

Horie: First is location. Our factory is in Taiki Town, and the launch site is just 10 minutes away. Companies like SpaceX in the US have to haul their rockets thousands of kilometers on highways from their factories. Next is launch frequency. For example, Tanegashima can only manage a few launches per year if they avoid fishing seasons, but around Taiki Town, fishing frequency is lower, so we can expect more launches. Another clear advantage is Japan's maritime location, allowing simultaneous launches east and south. This is an optimal condition for rocket launches. Globally, only Japan and maybe Hainan Island have this?

Inagawa: Well, New Zealand too.

Horie: Right, New Zealand can do it too. So, aiming for high-frequency launches also means frequent logistics. Japan is super advantageous here too. I think the only countries besides Japan that can build rockets using only domestically sourced parts are the US and China. Plus, Japan's small land area means transportation doesn't take long. Overseas companies inevitably rely on foreign supply chains, and their various bases for experimentation, assembly, and launch are widely scattered. Transporting and moving components between them takes time, so Japan has an overwhelming advantage in responsiveness and cost reduction. Furthermore, being able to build everything with Japanese parts means we don't get caught up in the U.S. ITAR (International Traffic in Arms Regulations) restrictions, allowing us to sell rockets to Europe and Southeast Asia.

Inagawa: Currently, there's high demand for launching small satellites, and globally, rockets are in very short supply. So even though Rocket Lab is leading the way, I don't think they alone can meet all the demand.

Sasagawa: If ZERO's commercialization succeeds, what will happen to IST?

Horie: The entire landscape would change. The moment we launch ZERO, IST's standing in the global space business market would skyrocket. Once we reach that point, securing funding becomes feasible. That would allow us to rapidly scale up to larger rockets. SpaceX launched Falcon 1 in 2008 and the scaled-up Falcon 9 in 2010. If IST follows a similar timeline for developing large rockets, we could be on par with SpaceX in 4-5 years. Well, in the meantime, SpaceX will likely be developing crewed vehicles like Starship, which Mr. Maezawa (Yusaku Maezawa, CEO of Start Today) will ride in 2023.

Sasagawa: I see. In the unmanned domain, we could catch up to SpaceX in 4 or 5 years.

Inagawa: Of course, that's where we want to be. Ultimately, the market will likely settle with a few companies remaining in each segment—regional, rocket size, satellite size—so our goal is to secure a strong position there.

Yoshida: While various space business ventures are emerging in Japan, very few companies are seriously tackling rocket engines. There's a drama called "Idaten" airing now, but back then, marathon running was said to be only for specialists. But now, tens of thousands of people compete in it. Similarly, rocket engines might shift from being developed solely by experts like JAXA to private manufacturers thinking, "If IST succeeds, we can too!" When that happens, we can support those manufacturers while steering JAXA toward pioneering research. That's the co-creation goal with IST.

Horie: Our role boils down to creating rockets that are incredibly cheap, enabling a future where we can launch things left and right. We want to establish a transport system that makes space exploration missions accessible. To achieve this, we want to research making ion engines—used in Hayabusa2—more accessible. Currently, the transport system is the bottleneck holding back research. If we can cut transport costs, wouldn't that free up more budget for satellites and probes? The US has already fully pivoted in that direction, right?

JAXA's Kakuda Space Center

Yoshida: No matter how much we discuss space, we can't get there without rockets. What I always notice in our co-creation activities with IST is that startups have a completely different sense of cost. Going forward, JAXA also needs to leverage more affordable private-sector technologies.

Horie: Eventually, we'll likely enter an era where "all transportation is handled by the private sector," right?

Sasagawa: Just as NASA shifted focus from "low Earth orbit" to "planetary exploration" after SpaceX emerged, JAXA will also evolve, driven by IST.

Yoshida: I expect both the projects we tackle and our overall direction will change. If that happens, JAXA might even start using IST for testing. I think fresh minds like IST's could come up with better solutions.

Inagawa: Thanks to our partnership with JAXA, ZERO's development schedule now has the potential to be accelerated ahead of the original 2023 target. Testing has begun at Kakuda, and following the successful launch of MOMO-3, we've seen tailwinds in both funding and talent acquisition.

Horie: However, both ZERO's development and funding are just getting started, so there's still a long way to go. We sincerely hope everyone will take an even greater interest in the space industry and ask for your continued support.

The Kakuda Space Center, where JAXA, a national organization, and IST, a private company, collaborate on co-creation activities. The landscape of space development is undergoing significant change.