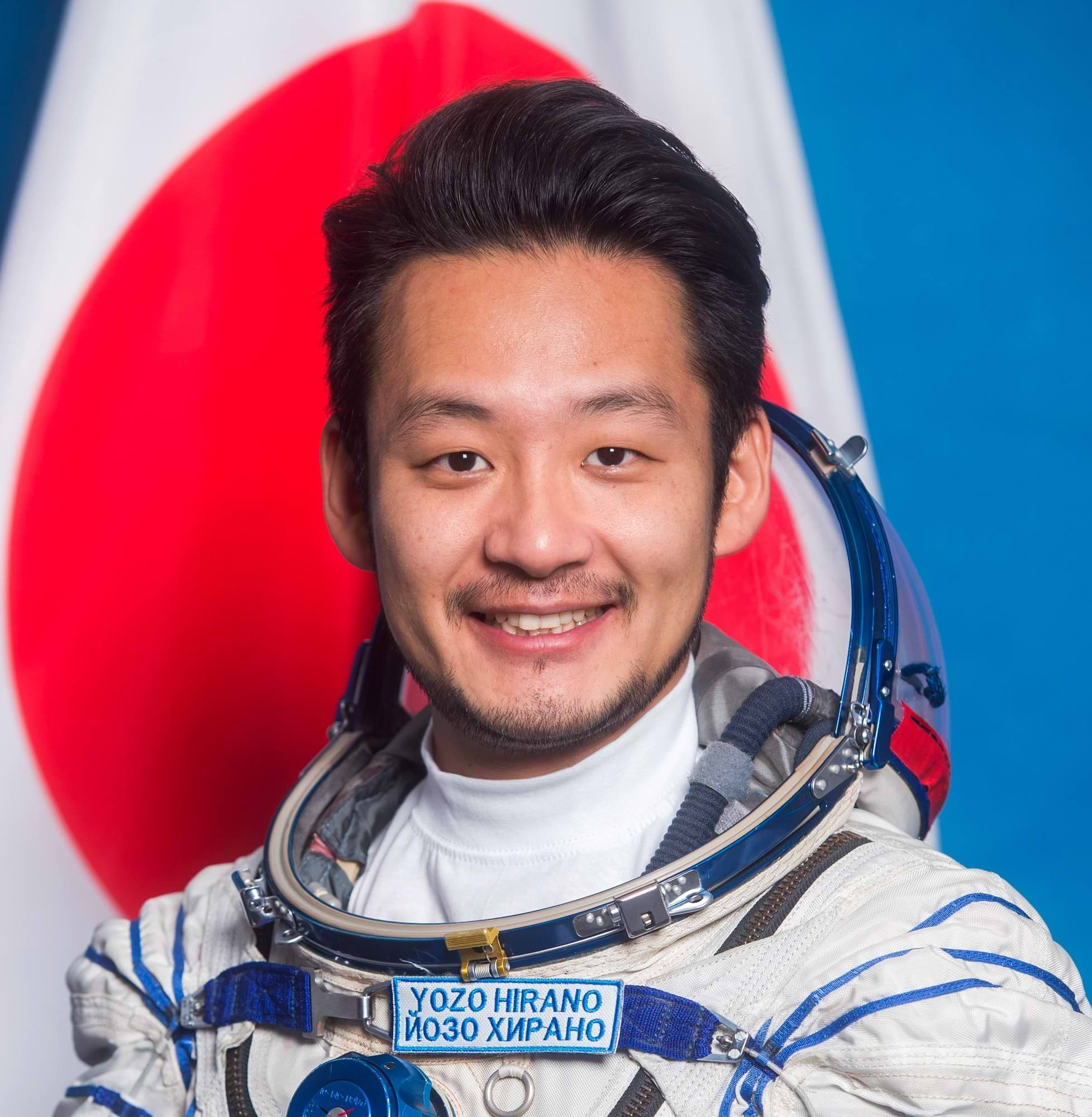

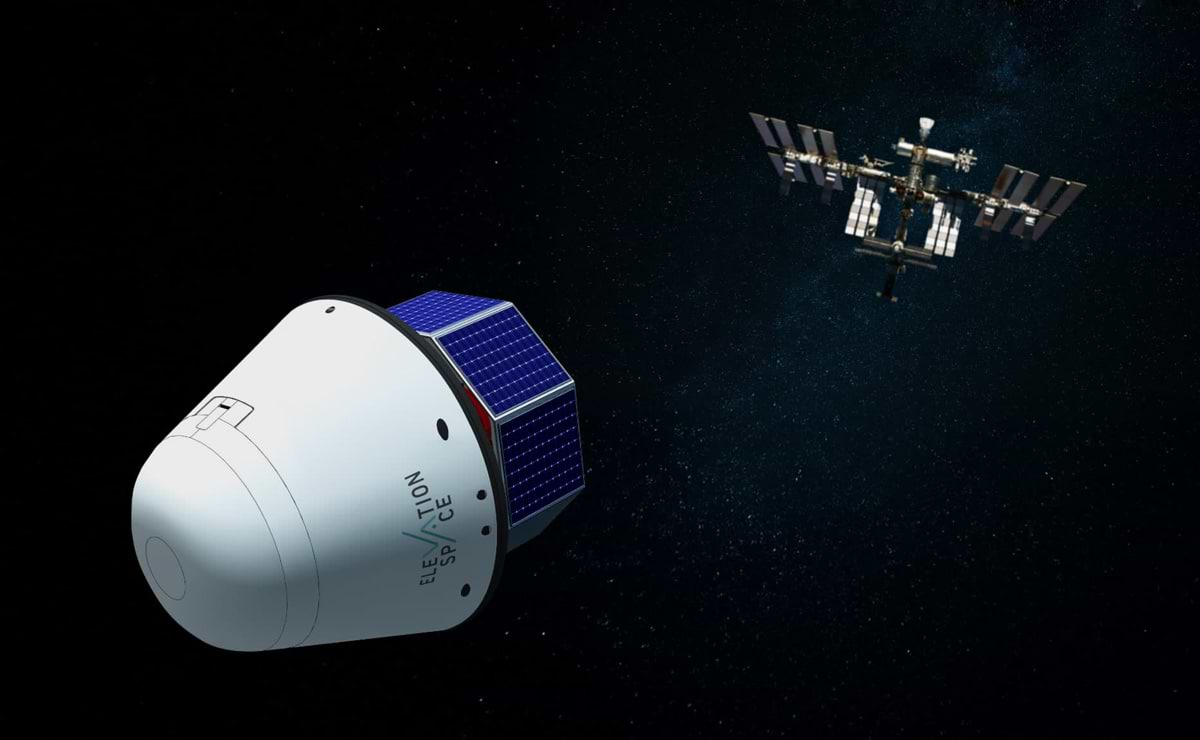

Yusaku Maezawa, CEO of Start Today, and Yozo Hirano, an executive of a related company, finally launched into space as "private astronauts" on December 8 (Japan time). The Soyuz spacecraft "MS-20" carrying the two successfully launched and arrived at the ISS (International Space Station). They spent approximately 12 days on the ISS as the first Japanese civilians, safely returning to Earth on December 20.

In the Space Editorial Department's special series " Yozo Hirano Goes to Space, " Yozo Hirano chronicled his daily life as a civilian astronaut for over two months. Mr. Hirano, who is also the manager of Yusaku Maezawa and a producer at Space Today Inc., which promotes space projects. After various events, Mr. Hirano ended up going to space. We were able to conduct a remote interview with him on December 4th, four days before the rocket launch, from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, where he was undergoing pre-launch isolation.

Sasagawa Makoto of the Solution Creation Center spoke with him about everything from his training to become a "civilian astronaut" to his real feelings just before launch.

Real-life civilian astronaut training, as recorded in his diary

Sasagawa: So, four days before launch. You seem calmer than I imagined. Is it a feeling of "I've done everything I can now!"?

Hirano: I think there was probably more I could have done, but there isn't much I can do now.

Sasagawa: I read the Space Editorial Department's "Yozo Hirano Goes to Space." Since it features Mr. Maeda and Mr. Hirano, who I'd presented to, I might be too emotionally invested to be objective, but I think it's a fascinating account of a private astronaut, rivaling Takaaki Tachibana's "Return from Space."

Hirano: Thank you.

Within the space information site "Space Editorial Department," the serialized diary

"Yozo Hirano Goes to Space," updated almost daily since September 12th, chronicles how Mr. Hirano unexpectedly (?) ended up aiming for space. It details trivia like how the sunglasses used in space have been made for years at an eye clinic tucked away in a corner of a shopping center, and describes the training in meticulous detail.

Sasagawa: How has it been lately?

Hirano: The intense training is over. Physical training is just enough to keep me moving comfortably. There's a 30-minute to 1-hour review lecture each day, covering only the crucial points. Things like the launch sequence, or discussing with actual field personnel how the rescue team would operate if we had to make an emergency landing back on Earth. It's been pretty much like this since I arrived at Baikonur on November 19th.

Sasagawa: Civilian astronauts are isolated the whole time, right? Are you staying at the Cosmonaut Hotel in Baikonur now?

Hirano: Yes. There are rotating chairs, tilt tables (like a seesaw that flips you upside down), and systems for practicing manual docking—where the commander manually connects the spacecraft to the ISS. It's a hotel modified for astronaut training.

Sasagawa: In your serialized diary, you wrote you absolutely hated the rotating chair. In Moscow, Mr. Hirano lasted 5 minutes and Mr. Maezawa lasted 7 minutes. Did you manage to clear the 10-minute benchmark required for civilian astronauts?

(Excerpt from Space Editorial Department's "Yozo Hirano Goes to Space.") You sit in a chair with a rotating platform, strapped in with monitoring equipment, close your eyes, and are spun around at high speed. Just the normal rotation makes you feel sick, but you also have to repeatedly tilt your head left and right in rhythm. After about one to two minutes, you enter a world unlike anything you've ever experienced in your normal life. Even though you're spinning horizontally, you're suddenly overwhelmed by the sensation of your body swaying dramatically back and forth, as if you were on a swing or a gondola. If you get thrown off that large wave, you're hurled into a tornado world where everything spins wildly in all directions. Once that happens, it's over. Nausea hits you immediately, and you either keep going until you vomit or retire right then and there.

Hirano: I safely completed 10 minutes at Baikonur. You do get used to it, but even now, the spinning chair still makes me feel sick.

Sasagawa: What about hypoxic training?

Hirano: That's just sitting and breathing. It depends on the person, but you know how some people find diving oxygen tanks tough or uncomfortable? For them, it's a bit rough. Otherwise, it's just training to breathe slightly thinner air. It does make you a bit sleepy, though.

Sasagawa: Speaking of sleepiness, I read in your diary series that when three adults are crammed into the tight confines of the Soyuz spacecraft, an overwhelming urge to sleep hits you. Does that happen to all astronauts, not just you?

Hirano: They say everyone does. But the commander sitting in the middle has tasks to do constantly, so they're moving the whole time. So I think the commander absolutely cannot sleep. For me, with a lot of waiting time, it was a daily battle against sleepiness.

The sequence from departure in Japan to launch, based on the serialized diary

Sasagawa: The serialized diary details training meticulously, complete with valuable photos—physical training, survival drills for emergency landings, ZERO-G flight training, spinning chairs, hypoxic training, practical training in the Soyuz simulator, and more. Among these, what was the most challenging?

Hirano: The final exams had an ISS segment and a Soyuz segment, both entirely practical skills. We practiced them daily to the point where anyone could memorize them after that much repetition. We even did full run-throughs beforehand, so I never imagined failing the practical skills.

What was tougher were the four oral Q&A sessions. They were conducted in English. Senior officials from Energia and Roscosmos, called the commission, came to verify whether we understood what the GCTC (Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Center) instructors had taught us. Both the questions and answers were in English, so it felt almost like exam preparation. The night before, I studied late into the night with Maezawa and Ogiso from the project team.

But even though it must have been exhausting and difficult at times, it's strange how I immediately forgot that once it was over, and now I mostly remember the fun parts.

A Space Project Made Possible by Being a Civilian Astronaut

Sasakawa: As you mentioned in your diary, the "Free Rocket Launch Tour Invitation" project—which required applicants to include at least one child under 12—received 8,000 applications on the very first day, even while you were training and involved in planning.

Hirano: Actually, despite the short two-day application period, we received over ten thousand applications.

Sasagawa: And you had to choose just one group from that. That must have been a tough task.

Hirano: The condition was that they absolutely had to bring a child. Plus, with the COVID situation and the application period being only two days from the announcement... We predicted a few thousand at best, so we were shocked to see so many. Over ten thousand families wanted to see the rocket with their children, wanted to show it to them. It was a moment when I truly felt the pull of space.

Sasagawa: That's incredible. The winners are so lucky.

Hirano: More than luck, it was passion that won first prize. They submitted forms explaining why they wanted to go, along with videos and photos. We even held remote interviews. I wasn't involved in the final decision, but other staff made it after speaking with them. It wasn't just the parents; the children genuinely loved space and wanted to see the rocket. We chose one family whose pure passion came through.

Sasagawa: For the "100 Things I Want Yusaku Maezawa to Do in Space" campaign we ran in May, how many do you think can realistically be done during a roughly 12-day stay on the ISS?

Hirano: For now, we're determined to complete all 100. Regardless of whether we can capture visually interesting scenes, we decided to go for it and opened the call for submissions. We're prepared to do everything, whatever the outcome may be.

Four days before the rocket launch. My real feelings right now

Sasagawa: Mr. Maezawa, Mr. Hirano, and Commander Alexander Misurkin, who will be going to the ISS with you, all seem like very admirable people. Mr. Hirano calls him Sasha, right?

Hirano: He's a gentleman. When he was a rookie astronaut and visited Tsukuba for JAXA training, he said that astronaut Koichi Wakata treated him very well. More than ten years later, he told me that he could repay that kindness by serving as our commander, which really touched my heart. I'm grateful to Mr. Wakata.

Sasagawa: What a wonderful story. Sasha, Mr. Maezawa, and Mr. Hirano's official portraits are great, aren't they!

(From left) Yozo Hirano, Alexander Mishurkin, Yusaku Maezawa

Hirano: Yes, yes. Even now, I think it's great that those photos were approved as the official ones. I think most photos of astronauts tend to have a somewhat solemn atmosphere, but I think that when people look at them in a few years, they'll think, "This crew looks like they're having fun," so I'm glad we went with those.

Sasagawa: The launch on December 8 was scheduled for 4:38 p.m. Japan time, which is quite specific, isn't it?

Hirano: Exactly. It was down to the second.

Sasakawa: You help with the hatch opening when boarding the ISS, right?

Hirano: No, Sasha handles the hatch opening all by herself. I'm responsible for equipment only accessible from the sides, like turning switches on and off. Also, when moving from the lower return module to the living module, I help prevent moisture condensation—basically, I act as a dehumidifier. It's simple work, but once I confirm the pressure is properly equalized between the upper and lower sections, with no pressure difference, Sasha gives the handle a firm twist and opens the hatch.

Sasagawa: You've practiced the hatch opening sequence countless times, right? It's drilled into your head?

Hirano: That's right. But we absolutely can't move until Sasha gives the call, so as long as she remembers, there's no mistake (laughs).

Sasagawa: Looking back now, could you share a scene from your serialized diary that particularly stands out?

Hirano: The scene I remember most vividly from writing the diary was around the fifth day of early training, when we met the four NASA astronauts who had already flown ahead to the ISS for the Crew-3 Mission. I couldn't even answer their simple question, "What's your top goal you want to accomplish in space?" properly, and self-loathing just washed over me.

That day, back at the hotel, I actually cried in front of everyone. You don't cry as an adult, right? Even though going to space was decided, and I felt nervous, excited, and anxious, I'd come this far thinking, "Well, it'll work out somehow," without any real resolve. Meeting the NASA astronauts finally made me understand that. I realized I couldn't go on like this; going to space like this would be disrespectful.

Sasagawa:The scene in the sauna after training in Russia also left a strong impression. Through conversations with astronauts who couldn't yet go to the ISS but were training diligently, I was deeply moved by the moments when Hirano-san reflected on his own situation by comparing it to theirs.

Sasagawa: Four days until launch. How are you feeling now?

Hirano: I haven't completely let go of my worries yet. I still constantly wonder, "Am I really the right person for this?" And, I'm not sure if I should say this, but there's this keyword about the democratization of space, this idea that a private era is coming. But honestly, I still feel it's far from easy, both financially and physically. I just happened to be close to Maezawa and happened to get taken along. Realistically, I think it's unlikely that an era where anyone can easily go to space will come soon. My training has only reinforced that feeling, and I've become more convinced that space isn't a place you can just casually visit.

Lately, Maezawa and I talk daily about things like, "It's less than a week now," or yesterday, "Only five days left, isn't that crazy?" Of course. But I think the feelings we have right now are completely different. Maezawa decided to go himself, paid for it himself, and blazed this trail himself. I, on the other hand, got swept up in the storm and ended up here. We're aiming for the same destination, but what we feel now is entirely different.

Sasagawa: I'm looking forward to reading your account of your state of mind three days before, two days before, and on the day of the launch in "Yozo Hirano Goes to Space." I know it's a bit premature, but after you return to Earth from the ISS and are discovered, where will you go?

Hirano: After recovery, I'll head to the airport in Kazakhstan by rescue helicopter that same day and return to the GCTC near Moscow that same day. Since it's a short stay of about 12 days on the ISS, they'll check for any physical issues. If I'm cleared as okay, I should probably be able to leave within a few days.

Sasagawa: So it sounds like you'll be able to return to Japan for the New Year's holidays?

Hirano: Yes. I believe I'll be in Japan for New Year's.

Sasagawa: Once you're safely back on Earth, I'd love to hear more about your experience.

Hirano: Absolutely. Let's have a relaxed chat.

Sasagawa: Mr. Hirano, have a good trip. Take care.

The Space Editorial Department's special series "Yozo Hirano Goes to Space" is here

Watch footage from the ISS on the MZ YouTube channel here