Hello, I'm Natsumi Wada from Dentsu Lab Tokyo.

My parents are deaf and use sign language as their primary means of communication. Consequently, I grew up in an environment where I primarily used Japanese Sign Language, a visual language, at home, and conversed using Japanese, an auditory language, outside the home. This background provided me with many opportunities to reflect on "communication" as an interpreter.

To interpret between people who converse by leveraging visual imagery and those who label the world around them through sound, diving into each culture and way of thinking, I realized "words" alone were utterly insufficient. During my university years, I studied interaction design and research design. Since joining the company, I've been exploring the possibilities of "technology" and "communication."

What does it mean to converse with images?

Languages like English and Japanese, which label various objects and concepts worldwide—like "cup" or "desk"—have developed by combining the smallest units of sound.

In sign language, a visual language, while objects may sometimes be symbolically named, there is a fundamental grammar called classifiers (CL ) where the hand is used to trace and shape the object itself in space, as if drawing it.

(Left: Expression for cup, Right: Expression for desk)

CLs are hand gestures representing an object's shape, properties, size, or movement. They share similarities with Japanese counting patterns: long, thin objects like pencils are counted as "~hon" (pieces), while thin, flat objects like paper are counted as "~mai" (sheets).

Reference: 'If Sign Language is a Language' (edited by Mori Sōya and Sasaki Rinko, Hitsuji Shobō), page 13.

This time, I'd like to share just a few examples of visual ideas and jokes that can only arise because it's sign language (these are by no means universal, but rather from everyday conversations around me).

Let's go on an adventure as a tiny version of ourselves.

When I was little, my father and I had "adventure time" after dinner. During "adventure time," we'd make a peace sign, point it downward, and use the index and middle fingers as legs to create a tiny version of ourselves.

In sign language, moving fingers like this to represent legs expresses actions like "walking," "swimming," "flying," or "diving." Every night, my father and I would create our little selves and have them climb over asparagus, swim through the stars in the night sky, or walk over our favorite words in books.

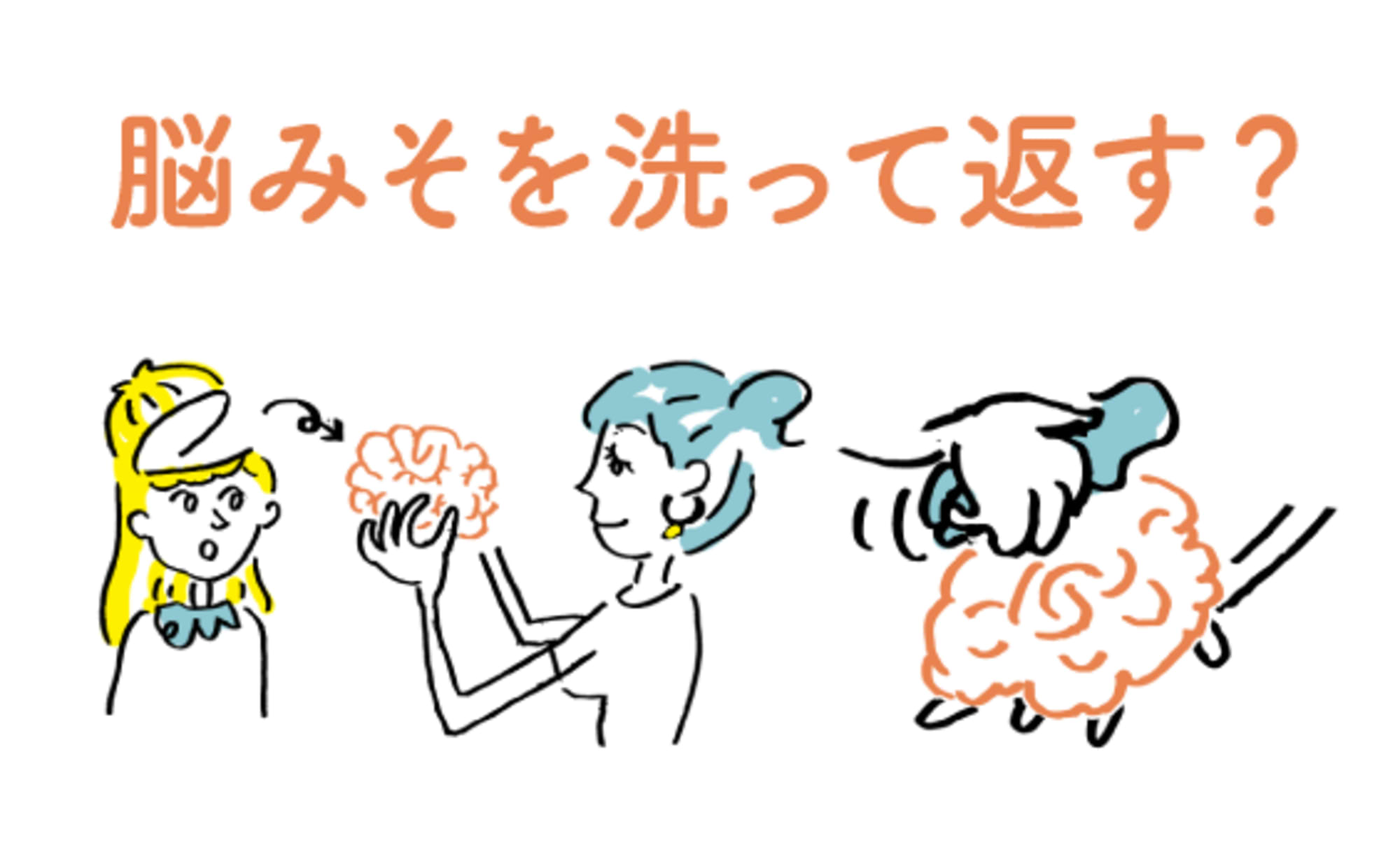

Wash the brain and return it.

When advising a friend, "You might want to reconsider that," sometimes with a bit of humor, I'll make a gesture of cutting off their head, taking out their brain, scrubbing it vigorously, and returning it.

When I want to say, "I'm not there, but I want to see it!", I take out one of my eyes and fling it in the direction of what I want to see, creating a conversation as if I were actually watching. Using my hands freely, visual ideas flow one after another, plunging me into a sensation like diving into a fantasy world.

Visual Creativity, Fantasia

The jokes born from this uniquely sign language visual communication possess a creativity that stems precisely from being visual. I'd like to explore this "visual creativity" a bit further.

In his book Fantasia, Italian artist Bruno Munari summarizes the "visual creativity" born from collage, metaphorical devices, repetitive expressions, and visual communication as follows:

"Primitive fantasia arises from reversing a situation or using opposites, contraries, or complementary elements. – Telling a child sugar is bitter makes them laugh heartily; telling them about a flash-fast turtle delights them immensely."

Fantasia, Bruno Munari, translated by Yumi Kanno, Misuzu Shobo, p. 38

Another aspect of fantasy arises from visual similarities and relationships with other properties. — For example, observe this ordinary fork. Doesn't it look like a small hand? A small fork with fingers, a palm, and a forearm up to the elbow. From that moment, you can pick up a soft fork (a cheaper, ordinary one) and use pliers to give this utensil any expression of a hand.

Fantasia, Bruno Munari, translated by Yumi Kanno, Misuzu Shobo, pp. 63-64

In other words, by inverting or altering our perception or image of an object, we can visually create "surprise."

In the earlier example, while you can't actually throw your eyeball like a ball, treating its round shape as if it were a ball creates the image in the other person's mind: "What if the eye flew off into all kinds of worlds?"

Munari not only created works utilizing this visual thinking itself but also developed numerous tools, play methods, and games that various people could create. I think drawing, collaging, expressing with hands, face, and body, and shaping and expressing images can draw out "visual thinking."

The History of Print That Cultivated Visual Thinking

This year, I participated in the Young Cannes Print Competition in Cannes, France, alongside art director Momoko Negishi. While studying the history of print advertising worldwide to prepare for the 24-hour endurance competition, I encountered an abundance of outstanding print ads that masterfully utilized visual imagination.

Posters and graphic expressions often conceal abundant "visual thinking" that employs various analogies and comparisons to instantly convey intent. They captivate viewers by adding playfulness to familiar concepts, creating "surprise" to achieve instant communication.

Examples utilizing this "visual thinking" are featured in the book 'A Smile in the Mind: Witty Thinking in Graphic Design / Playful Design ─Witty Ideas That Capture Attention ', published by BNN Publishing in 2018.

For example, the page on 【MODIFICATION: Change】 demonstrates how embedding meaningful variations within the main image creates an experience where the perception shifts in the mind. In a magazine illustration expressing "jazz improvisation," the lines of a musical staff—a universally recognizable symbol of sheet music—are deliberately tangled and intertwined. This transforms the notion of "sheet music = something played following a flow" into "entangled = possessing unpredictable movement."

Similarly, the 2004 Economist magazine campaign featured on the 【AMBIGUITY: Ambiguity】 page uses an optical illusion-like expression. By folding and positioning the magazine itself to resemble a brain, it creates an image that looks like both a magazine and a brain, conveying the message "the magazine that makes you smarter" (Ogilvy & Mather Singapore, 2004. Page 34).

The history of two-dimensional poster creation is packed with fascinating ways to convey messages through imagery, such as expanding ideas from collages and visual metaphors.

Incidentally, this year's Young Cannes print category brief was: "Create a print ad idea for a 2019 winter Christmas campaign encouraging donations to WWF for wildlife conservation." The winning entry featured an aerial photograph of a Russian forest with the copy: "Anna, your present is under the Christmas tree." By deliberately "not showing the animals," it invites viewers to imagine their presence, conveying the message to donate for wildlife. "Imploring imagination without showing" is another form of expression that effectively uses words and images to evoke visual imagination.

The Century of Film and the Visual World

Now, smartphones have become indispensable in our daily lives. We can see what our friends are doing and what's happening in the world as if we were actually there with our own eyes.

Sharing our lives and the world we find beautiful on Instagram, collecting favorite worlds on Pinterest, and even capturing information about people's movements and gestures—things that were difficult to preserve before—can now be saved as data.

Much of the information and knowledge previously shared through "words" can now be recorded, stored, and communicated by each individual using video and images as tools.

Not only that, but we can now generate countless visual ideas using apps and tools. The fact that we can converse fluently using smartphones, much like spoken words, might mean humanity has acquired a "new way of communicating" akin to language.

Having acquired this "new way of communicating," what exactly will we convey, and how will we expand our thinking?

"Conversing with Images"

For example, today, why not try expanding your ideas and communicating with family, friends, or loved ones using various methods—whether gestures, sign language, video, or animation?