Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

Highly Skilled IT Professionals Solve the "Delivery Route Optimization Problem" in the Logistics Industry

Ken Matsushita

OptiMind Co., Ltd.

Naohiro Takahashi

AtCoder Inc.

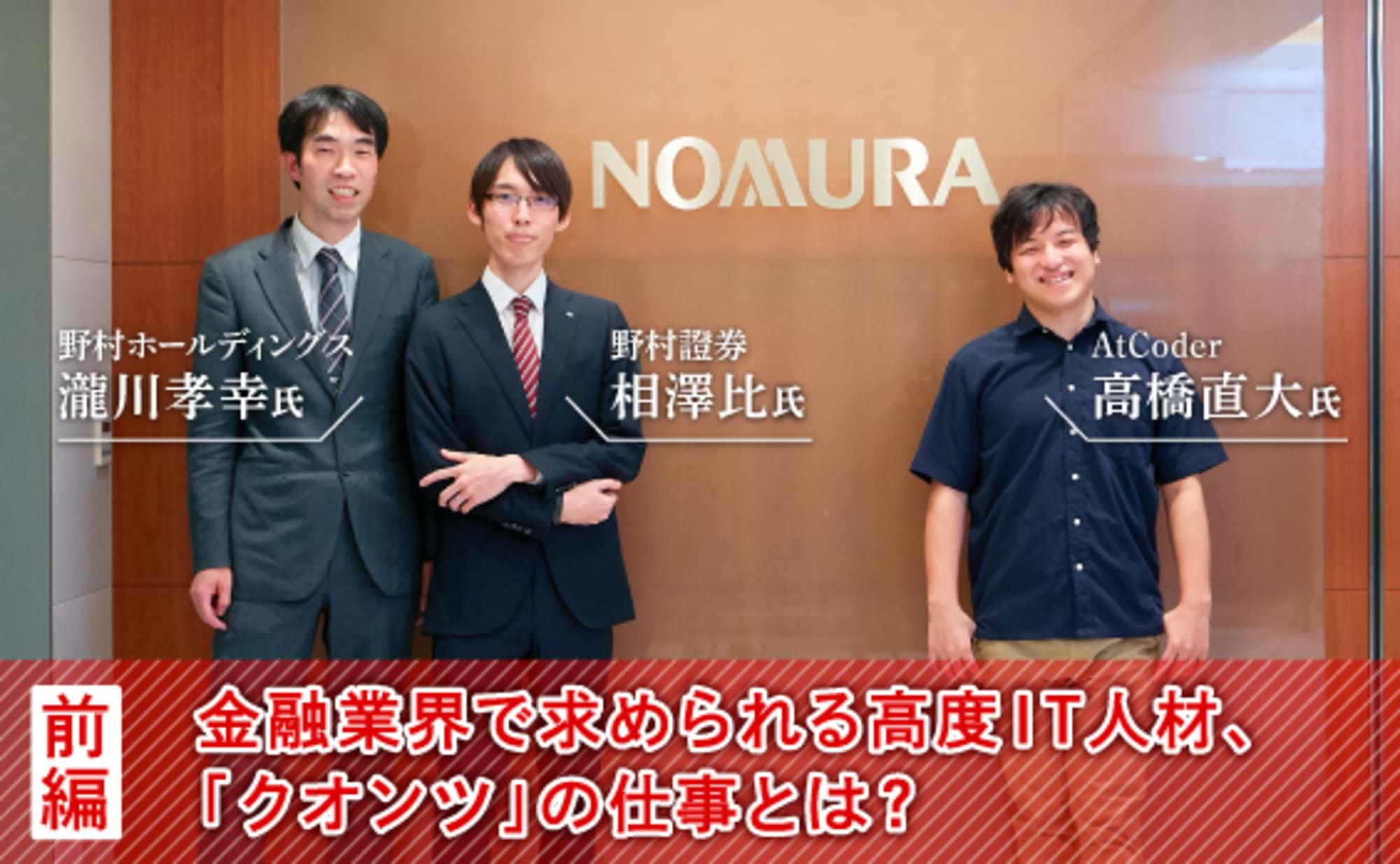

This series explores the cultivation and recruitment of "highly skilled IT professionals" with exceptional algorithm development capabilities, featuring Naohiro Takahashi, President of AtCoder and a key figure in the competitive programming world.

This installment features a discussion between Mr. Takahashi and Mr. Ken Matsushita, President of OptiMind, a startup with the mission to "optimize the last mile worldwide."

Last-mile route optimization—presenting the optimal sequence for which vehicle visits which destinations—is known as the "delivery planning problem." It is a theme long studied academically while also being a problem directly impacting business for the logistics industry.

We had the two passionately discuss OptiMind's initiatives—which have garnered significant attention, including raising over 1 billion yen in funding from companies like Toyota Motor Corporation—and how highly skilled IT professionals can make a significant impact in the logistics industry.

Encountering "Combinatorial Optimization": This is research that can solve societal challenges!

Takahashi: I've long wanted to speak with Mr. Matsushita, who is tackling logistics industry challenges by applying "combinatorial optimization" – a staple in competitive programming – in real-world applications. Could you briefly share your background and tell us about OptiMind?

Matsushita: After entering Nagoya University's Faculty of Information and Culture, I learned about "combinatorial optimization," which Professor Mutsunori Yanagaura was researching. I was convinced this was research that could solve societal problems, so I joined Professor Yanagaura's lab.

Matsushita: However, I found it puzzling that despite being such excellent research, it wasn't being utilized at all in the real world. So, I visited various industries and learned that applying combinatorial optimization technology was particularly difficult in logistics operations. I chose this field because the challenges were significant and it represented a market where combinatorial optimization could truly shine.

Wanting to bridge this outstanding research in "combinatorial optimization" with logistics operations, I founded a company while still a student and developed the route optimization cloud service "Loogia." This service solves the "delivery planning problem" – determining the optimal sequence and route for which vehicle should visit which destinations. Our business involves providing this service to companies as SaaS(※1) or via API(※2).

※1=SaaS (Software as a Service)

A software service model where users access only the necessary features, as needed, rather than purchasing a one-time license.

※2=API (Application Programming Interface)

A mechanism that partially exposes a software's functionality, enabling it to share features with other software.

Takahashi: What kind of companies are OptiMind's customers?

Matsushita: Primarily, they are customers handling the last-mile delivery—the final leg of logistics from the distribution hub to the end user. Common examples include home delivery companies and meal delivery services. We also have many companies engaged in "store delivery," transporting goods to convenience stores, drugstores, hospitals, and similar locations.

Takahashi: I see. So it's an algorithm for the last mile. I assume the "combinatorial optimization" algorithm is based on the "Traveling Salesman Problem" (※3), which is often featured in competitive programming contests.

※3 = Traveling Salesman Problem

A problem where distances between several cities are given, and the goal is to find the shortest route that visits all cities.

Matsushita: That's right. As you probably know, Takahashi, if there are 20 delivery locations, for example, determining the optimal order to visit them—by trying every possible sequence—results in 243 quadrillion combinations. If you tried to find the optimal route, the "exact solution," by exhaustively checking each one, it's said it would take even a supercomputer about 80 years.

Therefore, for practical business use, we don't aim for the "exact solution." Instead, we make educated guesses like, "This seems like a reasonably good solution," calculate it, then identify another promising solution to calculate... and so on. Within the available time, we keep making these educated guesses to find a "reasonably optimal solution." In other words, we seek an "approximate solution," not the exact one. We continuously refine algorithms to find the best solution within a given time limit, like 10 minutes.

Constraints inherent to the field. The algorithm alone won't suffice.

Takahashi: For the simple "Traveling Salesman Problem," countless studies already exist. If there are only 20 locations to visit, it's considered a beginner-level competitive programming problem where exact solutions are expected. Even with 1000 locations, using the latest algorithms, it's no exaggeration to say exact solutions can be derived instantly, barring special circumstances.

However, the biggest difference between the competitive programming world and widely known research is that in real-world work, you must consider numerous constraints like "delivery must be made between X and Y o'clock at the specified location."

Matsushita: Exactly. Specifically, there are over 40 "constraints." Beyond the delivery time windows, there are driver working hours, break times, and required certifications. For vehicles, there are load capacity constraints. We have "multi-temperature" vehicles that can carry both refrigerated and frozen goods. Since it's wasteful to have empty space in either compartment, we need to plan to fill both temperature zones to capacity.

Additionally, when multiple parking spots are available at a delivery location, we must calculate the optimal spot considering the positions of preceding and subsequent delivery destinations.

On top of that, there's the "pick-and-deliver" constraint. This means routing must consider the "sequence" of picking up the cargo first and then heading to the delivery location to unload it. Something humans understand intuitively, like "cargo can only be unloaded after it's loaded," is actually something computers can't automatically factor in.

Additionally, we must factor in traffic conditions during different time periods. While it might sound simple when described in words, incorporating all these constraints into an algorithm is proving quite challenging.

Takahashi: From a competitive programmer's perspective, when tackling a delivery planning problem, several foundational algorithms like the 2-opt method (※4) come to mind. But if you rearrange the route to optimize distance, you'll likely violate almost every constraint—pickup & delivery, time windows, and so on (laughs). The fact that standard optimization algorithms for the standard traveling salesman problem don't work at all makes this incredibly difficult.

※4=2-opt method: A method where two edges are randomly selected from the route and swapped. If this reduces the distance, the new route is adopted. This process is repeated.

Matsushita: But the fundamental approach itself is the same as general algorithms. We make a rough guess, perform random calculations, and then relentlessly let the computer solve how to improve further. It's tough, but it's incredibly interesting and rewarding.

The Difference Between "Research" and "Business": What Are the Challenges for University Startups Venturing into Business?

Takahashi: You mentioned starting the company to bring university research outcomes back to society. As a university-spinoff startup, where do you see your strengths and weaknesses?

Matsushita: Our strength lies in collaborating with academia to build systems with guaranteed quality. At our company, Professor Yanagaura—my mentor and a world-leading researcher in this field—serves as our technical advisor. In hiring, we also benefit from strong connections to Professor Yanagaura's lab and students, making it easier to recruit talent directly relevant to our technology.

On the other hand, our service originated from university research, making it essentially "product-driven." This is a weakness because no matter how excellent the algorithm, it won't sell on its own. We feel we have a disadvantage compared to entrepreneurs who come from a business background when it comes to not just creating something good, but turning it into a viable business.

Takahashi: I see. Even so, I think it's remarkable how you've steadily expanded the business, including securing over 1 billion yen in funding with Toyota Motor as the lead investor. By the way, what are the differences between approaching a delivery planning problem from an academic perspective versus a business perspective?

Matsushita: In academia, you have fixed assumptions like, "Let's say Student A rides a bicycle at 20 km/h." But in reality, sometimes they ride at 10 km/h, sometimes at 15 km/h. It's even possible that Student A is off work and Student B is coming in instead. The big difference is that we have to build the algorithm around that uncertainty.

Another difference is where we focus our efforts. In academia, improving accuracy and speed is often the primary goal. For us, however, the impact on our clients' businesses is where we place the greatest emphasis.

Takahashi: What kind of impact specifically?

Matsushita: There are two major ones. First, if reducing driving distance cuts a driver's overtime by 30 minutes, and we can then reduce the number of drivers needed, what kind of business impact does that create? It's about improving ROI-type metrics.

The other is the rapidly growing demand, especially during this pandemic-induced labor shortage, for solutions that enable "anyone to handle delivery and dispatch."

Takahashi: Can algorithms solve that?

Matsushita: It involves developing algorithms that bring everyone closer to the level of highly skilled individuals. We gather insights from field staff about how they've traditionally handled dispatching using their own judgment, then translate that into mathematical formulas.

That said, the human mind is incredibly sophisticated. No matter how much we translate it into numbers, we can't surpass it. So, we're not aiming for "equivalence with veterans." We see the algorithm's role as enabling a new hire to perform at 80% from day one, compared to a veteran's 100% and a newbie's 30%.

IT talent and the business front lines. Is algorithm development capability alone insufficient?

Takahashi: I'm still an active competitive programmer myself... How do competitive programmers appear to you, Matsushita-san?

Matsushita: I feel I can't compete anymore myself (laughs). Our engineers also include members familiar with AtCoder, and we hold contests as an internal club activity. Having AtCoder-using employees compete and sharpen each other's skills is invaluable for our company, which must create excellent algorithms. I see them as a group we should continue supporting.

Of course, it's not that engineers who don't participate in AtCoder are inadequate, but in a way, since they're training even in their private time, I feel that those participating in AtCoder grow at a faster pace.

Takahashi: At a company like OptiMind, where you really need to dive deep into algorithm design, competitive programming skills are incredibly valuable. When analyzing massive datasets or performing complex calculations, being accustomed to thinking through logic makes a huge difference.

However, I believe competitive programmers need other skills to thrive at a company like OptiMind. For example, if AtCoder were to organize an algorithm team to tackle a delivery planning problem, they might catch up on the algorithms themselves.

Matsushita: I really hope they don't do that (laughs).

Takahashi: But I think it would take an enormous amount of time to understand "what the field actually needs." That's because it's difficult to articulate everything you're thinking in your head at once. Even after talking to someone from the field once, gaps in understanding would likely emerge later. Just aligning with one company is tough enough, but you'd have to coordinate with multiple companies. Furthermore, the conditions change in detail depending on what you're transporting, right?

It's not just about creating an algorithm; the real challenge lies in genuinely engaging with each company and providing sincere support.

Matsushita: Not to toot our own horn, but I think that's exactly right, Mr. Takahashi. Our company's "secret sauce," so to speak, is having people who act as "translators" – who can grasp the on-site requirements and interpret them for our excellent engineers.

We require two key abilities from our engineers. The first is consulting-like capability. Often, just by listening carefully, we find solutions beyond algorithms. This ability to understand development requirements and solve business challenges is crucial. The second is the ability to formulate complex algorithms into mathematical expressions when "only an algorithm can solve it." We prioritize whether the solution is theoretically sound and can be considered from the upstream design phase.

What competitive programmers should know: Your stage isn't limited to web or gaming industries!

Takahashi: Beyond the abilities we discussed earlier, what other skills and mindsets would be beneficial for competitive programmers and other highly skilled IT professionals to thrive in society?

Matsushita: Previously, IT was introduced only for information visualization and management. Now, however, its adoption extends beyond logistics to the "decision-making level." That's precisely why I feel the ability to devise algorithms is becoming increasingly vital.

When our company hires, we certainly look at character traits like humility. But once that's met, the key points become foundational skills and the ability to think algorithmically. I also think it's good to have the mindset to challenge AtCoder (laughs).

Takahashi: Thank you (laughs). Also, in my personal view, many people studying IT, especially younger ones, seem to think IT professionals can only thrive in the web or gaming industries. Few seem to have the perspective of "solving real-world problems." But I want young IT talent to know that, like OptiMind, IT can also be leveraged to solve problems in the logistics industry.

Matsushita: You're absolutely right. For IT going forward, how it connects with real-world movements is crucial. In our case, it's about how we integrate IT into areas where trucks move, where goods move. I think it's vital to have the perspective of how much the technology we're researching can become a "tangible business."

Takahashi: Beyond logistics, there are countless problems in the world that simply can't be solved without IT. That's why I wanted to convey to competitive programmers: don't overlook opportunities where algorithms might be useful, or where optimization could be applied in completely different industries outside of IT. I hope they'll look at the world with a broad perspective. Thank you for today.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

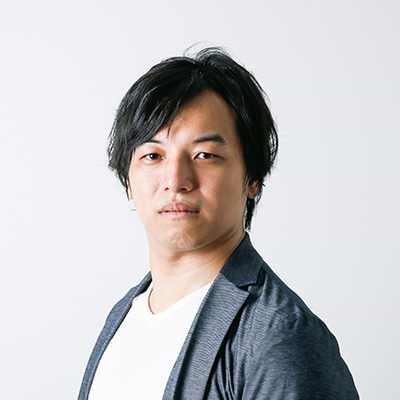

Ken Matsushita

OptiMind Co., Ltd.

President and CEO

Born in Gifu City, Gifu Prefecture. Graduated from Nagoya University's Faculty of Information and Culture, and is currently enrolled in the Doctoral Program in Mathematical Information Science at the Graduate School of Information Science. Founded OptiMind LLC in 2015. Successfully raised approximately ¥1 billion in funding from Toyota Motor Corporation and others in October 2019. Selected as one of Forbes Asia's "30 Under 30" entrepreneurs and innovators changing the world in April 2020.

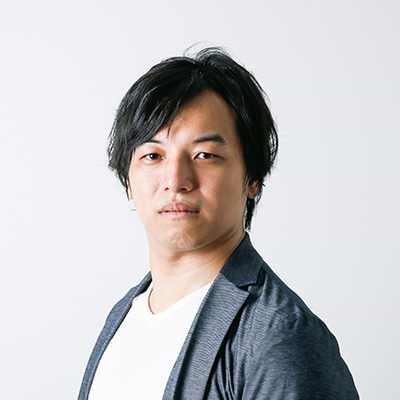

Naohiro Takahashi

AtCoder Inc.

President and CEO

Placed third globally in the Imagine Cup programming contest hosted by Microsoft. Subsequently achieved numerous top results in programming contests, including four wins at the ICFP Contest and two runner-up finishes at TopCoder Open. In 2012, founded the service "AtCoder" to host programming contests in Japan. It has since grown into a contest attracting over 7,000 participants weekly.