Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

Interpreting the LGBTQ+ Survey: Are the "Knowledgeable Bystanders" Unconsciously Contributing to Discrimination?

The Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab, which researches the field of Diversity & Inclusion (an approach aiming to respect each person's diverse individuality and promote social participation for all), conducted the large-scale "LGBTQ+ Survey 2020 " in December 2020, focusing on sexual minorities, including LGBTQ+ individuals.

This survey began in 2012, making this the fourth iteration. This series has already covered the results of the "LGBTQ+ Survey 2020" over the past two installments. In this and the next installment, Lab member Ayaka Asami, who moderated the session, introduces the content of the discussions held with experts based on the survey findings.

In this session, Professor Shinichiro Kumagai from the University of Tokyo and Fumino Sugiyama, CEO of New Canvas, took the stage. Based on the survey results, they exchanged views on trends in public opinion regarding LGBTQ+, as well as future challenges and expectations. This installment will interpret the first-ever "Cluster Analysis of the Straight Population's Attitudes Toward LGBTQ+" (※1), explained in the second installment of this series.

*1 Straight population: Defined as individuals who are heterosexual and whose assigned sex at birth aligns with their gender identity.

Shinichiro Kumagai: After graduating from the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Medicine, he worked as a pediatrician while living with cerebral palsy. He is currently involved in "participant-led research" at the University of Tokyo's Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, studying the relationship between disability and society. He published " The Art of Connection: Neither the Same Nor Different " (NHK Publishing), which deeply examines the difficulties people with disabilities face in connecting with others and the world, and " The Generation of <Responsibility>: The Middle Voice and Participant Research" (Shinyosha), which explores perpetrator-victim relationships and responsibility from the perspective of participant research.

Fumino Sugiyama: Co-representative director of NPO Tokyo Rainbow Pride, organizer of Japan's largest LGBT Pride Parade, and CEO of New Canvas. Involved in establishing Japan's first same-sex partnership system in Shibuya Ward. Former Japanese national women's fencing team member, newly elected director of the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC). Currently dedicated to raising his two children as a father, recently published " Trying Parenting as a Trio: Mom, Dad, and Sometimes Gon-chan " (Mainichi Shimbun Publishing). His book published last year , " Former High School Girl Becomes a Dad " (Bungeishunju) , also generated significant buzz.

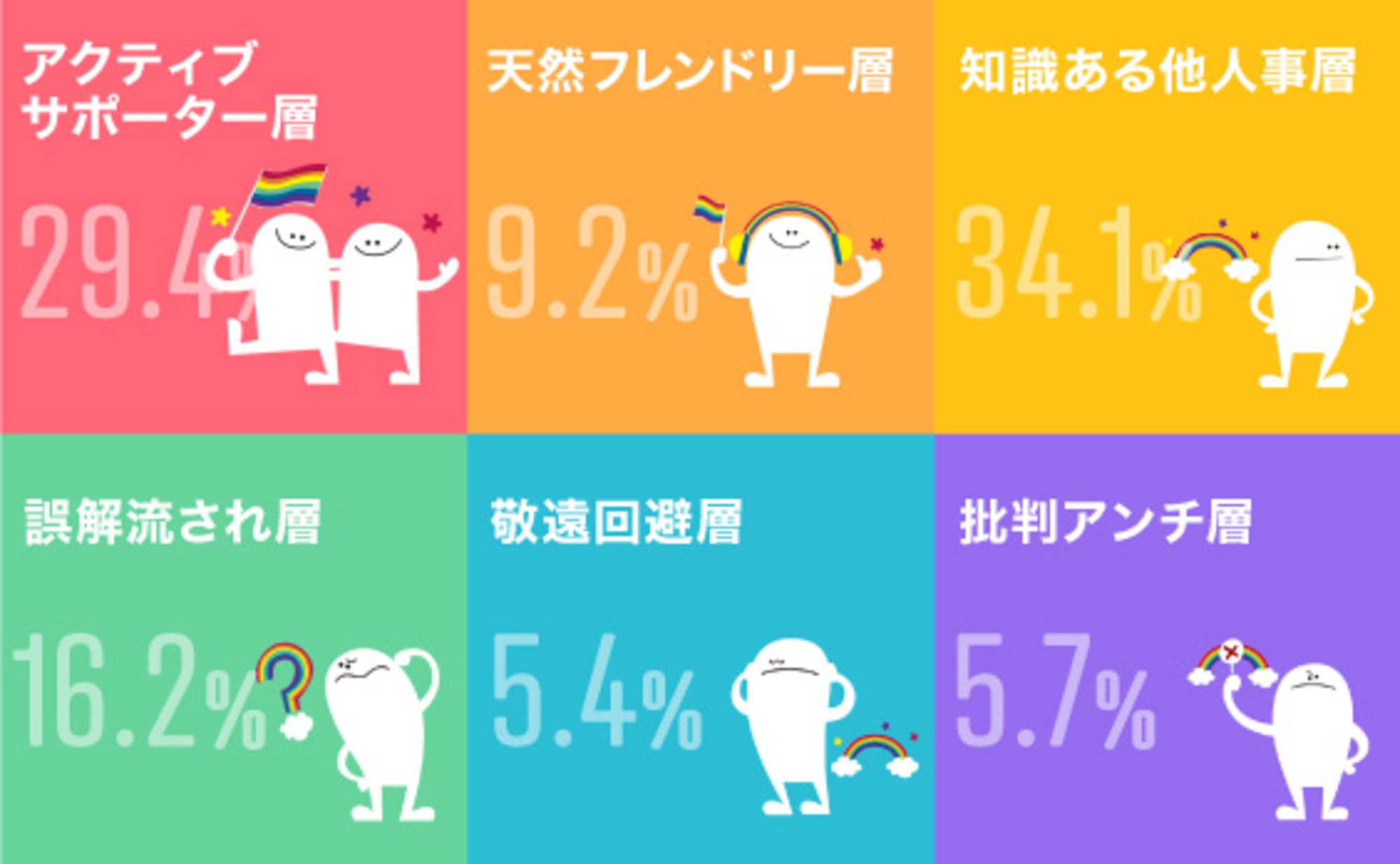

・Active Supporters (29.4%): Highly aware of the issues and actively supportive. Deepened their understanding through personal connections or overseas content.

・Naturally Friendly Group (9.2%): Low knowledge scores, but relatively high awareness of the issue and consideration, naturally open-minded.

・Knowledgeable Detached Group (34.1%): Possess knowledge but lack personal connection to the issue, such as having no close acquaintances affected. They favor maintaining the status quo.

・Misconception-Driven Group (16.2%): Appears critical due to widespread misunderstandings, such as concerns about negative societal impacts like declining birth rates, but fundamentally possesses human rights awareness.

・Avoidance Group (5.4%): Do not actively criticize, but lack consideration and avoid involvement. Possess some knowledge but do not perceive it as an issue.

・Critical Anti-Layer (5.7%): Exhibits strong physiological aversion and significant concern about societal impacts. Also shows disinterest in other social issues like racial discrimination or environmental problems.

For details, see Part 2 of this series.

For the lives of LGBTQ+ individuals to change, the mindset of the approximately 90% who are not part of the community must shift.

Asami: This marks our first attempt to present "Straight Group Clusters." Where do you see the value of this data, and how should it be utilized?

Sugiyama: I believe this data is extremely valuable. While we've long conducted LGBTQ+ awareness activities, there's quite a bit of data on the attributes and tendencies of LGBTQ+ individuals themselves. However, I think there has been a lack of clear data on the attributes of people outside the LGBTQ+ community.

When striving to create a more livable society for everyone, simply approaching LGBTQ+ individuals doesn't bring about change easily. It's the shift in awareness among the roughly 90% of non-LGBTQ+ individuals that ultimately changes the lives of LGBTQ+ people.

However, even within that 90%, people are diverse, so we've always struggled with how best to approach them to gain understanding. Therefore, having some understanding of their attributes and tendencies makes it much easier to approach them. I definitely want to make use of this.

Asami: By the way, how did the clustering turn out? Did it match your expectations, or were there any surprises?

Sugiyama: As a transgender person involved in various activities, I felt the numbers pretty much matched my lived experience.

These days, you rarely get outright rejection. But there's a huge group of what I'd call the "knowledgeable bystanders." Then there's the "naturally friendly group" – I thought that naming was really interesting. Honestly, I've felt that a lot of people are like, "Oh, that's cool, that's cool. Not my problem though." That's the reality, and it really matched my image and experience.

Asami: What about you, Professor Kumagai?

Kumagai: My primary focus has been on the field of disability, specifically on how to reduce discrimination, prejudice, and stigma (※2) against people with disabilities.

※2 Regarding stigma, Professor Kumagai will provide a detailed explanation later, but it encompasses phenomena like categorization, stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination.

In this research, I recalled that studies have recently begun focusing on individuals who hold stigma, examining "what kind of background influenced them to develop stigma."

For example, while some people perceive diversity using a categorical approach—such as "disabled" versus "able-bodied"—others use a "dimension" approach (*3), recognizing that experiences may vary in degree but are qualitatively continuous and share common ground. Comparatively, those who use the categorical approach tend to exhibit stronger discrimination and stigma.

*3 The dimension approach is a cognitive framework that views individuals as unique persons rather than categorizing them, seeking out shared "axes" of experience that foster empathy across different personal experiences.

What approach is needed for those who are easily categorized? Conversely, what approach is needed for those who adopt the dimension type? While this categorization itself feels somewhat categorical and is a bit concerning, a strategy gaining attention is that people who hold stigma are not a monolithic group. It is necessary to customize approaches to reduce stigma based on each individual's cognitive biases and their specific background.

In that sense, I believe this research, which clarifies that the majority—or rather, the people around them who may carry stigma—are not a monolithic group, will be highly valuable for considering how to customize approaches for each individual going forward.

Asami: You mentioned the keyword "stigma." Since some listeners might not be familiar with it, could you explain what stigma is?

Kumagai: Stigma is a concept first used by sociologist Erving Goffman to academically describe phenomena of discrimination.

We tend to categorize diverse people—rather than seeing them individually as "Kumagai" or "Tanaka-san"—and lump them together. For example, we might group them as "people with disabilities" or "LGBT individuals." We often stereotype them, thinking things like "LGBT people are like this," and frequently hold inaccurate images.

Not only that, but we may harbor negative feelings toward people belonging to specific categories. In severe cases, we might discriminate by excluding such people or, conversely, exerting peer pressure to conform. This phenomenon—this categorization, these stereotypes, prejudices, and discrimination—is collectively referred to as "stigma."

Asami: By the way, regarding this cluster, can we say this layer is more stigma-like, or that layer is more dimension-like? Or is it not that clearly divided?

Kumagai: I think it's very difficult to read that deeply into it. We'll likely discuss each cluster later, but probably, within any cluster, there might be both dimension-type people and category-type people. However, I imagine the "Critical Anti-Layer" is a cluster with a fairly clear, category-based stance.

"Knowledgeable Bystanders" Reveal "Diversity Without Inclusion"

Asami: I'd like to hear more about the individual clusters. The data showed that the "Knowledgeable Bystanders" cluster is very much the majority among Japanese people. What were your thoughts upon seeing this result?

Kumagai: I thought, "Ah, I see." Relating back to the stigma discussion, I believe that to feel it's not someone else's problem, some degree of personal contact with people in that category is necessary. Related to this, the idea that contact is crucial for reducing stigma is called the "contact hypothesis," a long-standing concept in stigma research.

For example, people with disabilities were often isolated in institutions, or in earlier times, confined within their own homes. This effectively blocked contact with those around them. In such situations, it inevitably becomes someone else's problem.

While LGBT individuals may experience less physical isolation compared to people with disabilities, they often find themselves in situations where stigma is pervasive, hindering their ability to openly share their feelings and experiences. This creates a situation akin to psychological isolation, where opportunities for their authentic selves to connect with others are consistently blocked.

Asami: Earlier, you mentioned that both dimension-type and stigma-type individuals exist within every cluster. While stigma is often associated with criticism or hate speech, what kinds of stigma exist among the "knowledgeable bystanders"?

Kumagai: In the disability field, this has been discussed quite a bit recently. It's a type of stigma where there's no objection to the direction of diversity, but it's like, "Just don't get too close."

For example, diversity might be accepted at a distance, but suddenly discrimination arises when renting a property, or becomes apparent when considering marriage. Discrimination occurs when seeking employment, or when attempting to engage in close, deep relationships where significant interests are involved. This kind of situation persists.

Some people refer to this as "diversity without inclusion." I sometimes think this situation—where diversity is acknowledged but inclusion isn't practiced—still persists.

Asami: You just mentioned the keyword "inclusion." Could you explain what that term means?

Kumagai: Diversity is a concept describing a state where specific attributes are distributed within a particular region, community, or organization in proportion to the overall population distribution of general society. Inclusion, on the other hand, is a concept describing the relationships between people.

The most crucial condition for inclusion is that equal opportunities are guaranteed. For example, for me, it means being able to go wherever I want and choose from various options, just like someone without a disability. Additionally, what's gaining attention recently is that the subjective feeling of belonging to an organization or community – that sense of belonging – is also considered an important element of inclusion.

Asami: So, is it accurate to think of inclusion as a state where both exist: the institutional option and the cultural sense of belonging, the feeling of actually belonging?

Sugiyama: You often hear things like "Everyone should be welcome" or "It's good to have all kinds of people," right?

But, for example, if someone says, "Kumagai-san, Asami-san, let's go out for drinks together. It's fine, right? The wheelchair doesn't matter. Let's go!" – if there's a step there, only Kumagai-san can't go. In that situation, if someone says, "Well, let's spend money to remove this step," others might ask, "Why spend money just for Kumagai-san?" That leads to a debate about whether it's truly equal. But if you say, "All citizens are equal," and distribute clothes of the same size to everyone nationwide, some people won't be able to wear them, right? Is it truly equality to make people who don't fit the size give up and endure?

I'm not sure if we can definitively say it's meaningless unless the people there are truly valued. But I think society won't change unless we recognize that diverse people exist and ensure all those diverse individuals can thrive and be valued.

Asami: I completely agree with you. Both choice and a sense of belonging, that atmosphere, become crucial, right? Mr. Sugiyama, how did you interpret the data suggesting Japan's majority is a "knowledgeable bystander group"?

Sugiyama: As someone directly involved, I often sense that many people have this attitude of, "Well, that's fine. It doesn't concern me." But I also don't think we can simply blame them. There's often no malicious intent behind it. I doubt there are many people who discriminate against LGBTQ+ individuals with actual malice.

It's more that they say those things precisely because they don't know, thinking they're doing good. This "other people's problem" attitude, I think, is really just another way of saying "indifference." Getting these indifferent people to become aware is incredibly difficult. Conversely, people who are very critical can sometimes become huge supporters once you just click that one button. But getting people who aren't aware to become aware – that's the real challenge.

Personally, though, what I often notice in diversity discussions is how people are described as "diverse" – like foreigners, the elderly, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and so on. But everyone gets old eventually. If I were to get into an accident on my way home today, I might end up in a wheelchair tomorrow. If I go abroad, I become a foreigner. And even if I'm not personally LGBTQ+, my child might be, or the partner my child chooses might be. Thinking about this, I realize that being part of the community and not being part of it are two sides of the same coin.

It wasn't until I became a wheelchair user myself that I suddenly realized, "Oh, there was a step here?" Do we only start demanding "Let's get rid of these steps!" once we realize we can no longer access places we used to? Or should we all take ownership of these challenges—problems we might never face personally, but could face tomorrow—and work together to solve them because they affect everyone? I firmly believe the latter approach is better for society. How we achieve that is something we need to start thinking about now. The key, I feel, lies in how we get people who see these issues as someone else's problem to start seeing them as their own.

Asami: Exactly. The relationship between those directly affected and those not is two sides of the same coin. Even if awareness doesn't kick in until you become directly affected yourself, wouldn't a society where we proactively work together to solve the problems of those we perceive as unrelated be better?

Sugiyama: That's why I believe there isn't a single issue that can be treated as someone else's problem. All social issues are interconnected—whether it's parties involved vs. bystanders, minorities vs. majorities, perpetrators vs. victims. Even I might be considered a minority if viewed through the lens of sexuality, but in other aspects, I belong to the majority.

This isn't limited to LGBTQ+ issues. I think it's probably universally true that the very issues we feel least connected to are often the ones where we hold a position of privilege, a so-called strong position. The ease of our own lives, which makes us feel disconnected, is actually built upon that privilege. Conversely, we might be contributing to the very structures that make life difficult for others. This is something I constantly remind myself of as a personal caution.

Asami: I see. So change might start with each person becoming aware that they might be an unknowingly privileged person, someone who might be contributing to creating these discriminatory situations. From the perspective of your research, Professor Kumagai, do you have anything to add about this?

Kumagai: When we read novels or watch movies, even if the situations characters face are completely different from our own, we can sometimes feel deeply moved or empathize, right? In other words, when we deeply understand someone's story, we can transcend categories and sense things like, "Ah, it's the same suffering," or "It's the same frustration." However, this empathy tends to remain shallow if it's based solely on knowing the other person's personal history.

Just as understanding the historical context in which a work of art like a painting was created is necessary for deep appreciation, we need to understand the history of the experiences and movements of people with disabilities, along with the unique values and wisdom accumulated within them. Furthermore, people without disabilities also need to reflect on their own personal history, the history and values they inhabit, and the privileges and wisdom they enjoy. The contact hypothesis emphasizes that deeply understanding and respecting both oneself and others, at both the individual and collective levels, is crucial for reducing stigma. This is what I meant earlier when I spoke of dimensions.

In other words, while it's true that the other person and I are different, when we deeply listen to or learn about their individual story and the collective experiences behind it, a common narrative—a sort of skeletal framework of life—surprisingly emerges. It becomes impossible to see it as someone else's problem. That is the meaning of contact. I have come to believe that, in this way too, we are beings capable of connecting in ways that transcend seeing others as separate.

To eliminate misunderstanding, criticism, and avoidance toward LGBTQ+, education to acquire accurate knowledge is necessary

Asami: Now, let's move on to the next cluster. Earlier, we discussed those who are indifferent or see it as someone else's problem. This time, we've identified clusters with very negative sentiments: the "misunderstanding and swayed group," the "avoidance and shunning group," and the "critical and anti-group." How should we engage with these groups? Professor Kumagai, please start.

Kumagai: What particularly caught my attention was the data on the "Critical Anti-LGBTQ+ Group." I felt the data also suggested a tendency toward low belonging to communities, society, or local communities – something we mentioned earlier as one condition for inclusion.

In terms of feeling socially excluded or marginalized, I wondered if some individuals assigned to this group—perhaps not all, but certainly some—might personally sense a degree of social exclusion.

This brings us back to the earlier discussion about approaches to stigma. I felt that an approach enabling them to share their own feelings of alienation or exclusion – precisely those feelings they themselves carry – might be necessary when engaging with this group.

Asami: In your research, I recall you mentioned that "people who cannot depend on others in a healthy way are more prone to stigma." What are your thoughts on that aspect?

Kumagai: People who are excluded by those around them or by society as a whole, who face discrimination, or in extreme cases, who are subjected to violence. Living in such situations naturally leads to distrust of people. Or distrust of society.

Distrusting people makes life difficult in many ways. When you're in trouble, you can't safely rely on or depend on those around you. Consequently, you end up having to overly depend on a limited number of people outside your immediate circle. This state is exhausting, so I've long considered how to enable broader reliance on the people around them.

In that sense, I'm very interested in whether people in this group are able to place themselves within relationships or communities where they can safely reveal their weaknesses, troubles, pain, and hurt, and feel they can rely on others.

Asami: Mr. Sugiyama, what are your thoughts? Could you share your impressions on how we should approach these three clusters?

Sugiyama: Regarding this cluster, as the name itself suggests – "Misunderstanding" – I believe gaining accurate knowledge is crucial.

Particularly, data shows that many of those expressing opposition tend to be slightly older. However, I don't think this is about blaming individuals. It's about education and the process of becoming an adult. Many people reach adulthood without ever having had a proper opportunity to learn about LGBTQ+ issues. Once you learn about it, it often turns out to be no big deal, but they simply never had that chance.

Information about LGBTQ+ or sexual minorities is often extremely biased and limited. For example, it might come from people in the nightlife industry or TV variety shows. I don't mean to imply anything negative about those industries, but the information is highly skewed. Because that's all they know, they tend to think, "Oh, so those people are like that," making that their only source of knowledge. So, ultimately, I think it's crucial to properly convey this information in educational settings.

Often when I bring this up, I get asked, "Isn't it too early for children?" There's a tendency to mistakenly think that LGBTQ+ topics are just about adult bedroom matters. But this isn't about sexual acts; it's about identity. So, it's not a matter of too early or too late. I believe it's something everyone should properly learn and understand.

Properly conveying these things in educational settings is incredibly important, not only to prevent children who are part of this community from experiencing unpleasant feelings or harm, but also to prevent the other children from becoming perpetrators.

For example, there was truly tragic news in the US about a 9-year-old boy who committed suicide after being bullied for saying he liked boys. But I suspect the children who bullied him probably didn't mean any harm. It's precisely because of ignorance that the hurtful words of thoughtless adults are reproduced, perpetuating this cycle of negativity and leading to such sad outcomes. Considering this, I believe education and acquiring knowledge is one key solution.

Asami: So education is the key. You think that could reduce the number of people who discriminate without meaning to?

Sugiyama: I truly believe those who make critical remarks also have no ill intent. They aren't saying these things to hurt anyone; they genuinely believe this is absolutely necessary for Japan to improve. So, I don't think this is a place for confrontation or conflict. Rather, I think it's incredibly important for us to learn about each other's areas of ignorance.

Asami: Speaking from a place of ignorance, a common misconception among those susceptible to misinformation was that recognizing LGBTQ+ individuals would lead to a declining birthrate. This tendency toward such misunderstandings emerged. From your perspective, Fumino, as someone with two children, how should we engage with this group?

Sugiyama: It wasn't until I started raising my own children that I began to understand this perspective. Having children or not is truly a personal choice; it's absolutely not something you have to do. But I personally wanted to have children. Raising children is truly enjoyable and a wonderful life opportunity.

I wonder if people who think this might accelerate the declining birthrate, or who oppose LGBTQ+ rights, are mistakenly assuming that LGBTQ+ individuals are consciously choosing to abandon having children. Essentially, many people have experienced raising children and consider it such a wonderful life opportunity. They might think that those individuals are voluntarily giving it up, that they aren't contributing to society – a perception born from a lack of knowledge.

That's precisely why I want to say the opposite: LGBTQ+ people don't dislike raising children or want to avoid having them. It's that when they do want to have children, the systems in place prevent them from doing so. There are societal structures that make it impossible. Understanding this, we must recognize that creating an environment where everyone can help raise the next generation isn't a negative for anyone. I truly want to dispel that misunderstanding. Becoming involved in raising children myself has made me think this even more strongly.

Asami: Listening to what you just said, Mr. Sugiyama, I feel like awareness truly starts to shift as we learn about each individual issue.

Looking Ahead to Next Time

This time, we discussed the value of our first cluster analysis of the straight population, the largest group being the "Knowledgeable Bystanders," and how to engage with the more negative groups: the "Misguided Followers," "Avoiders," and "Critical Opponents."

Next time, continuing our exploration of cluster analysis, we'll discuss how to interpret the "Active Supporter Group" and the "Naturally Friendly Group." We'll also examine how to interpret data showing that same-sex partnership systems contribute to protecting the human rights of those involved and improving local public opinion, and we'll share Q&A from seminar viewers.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Ayaka Asami

Dentsu Inc.

Second Integrated Solutions Bureau

Strategic Planner

As a strategic planner, I have been involved in marketing, management strategy, business and product development, research, and planning for numerous companies. In 2010, I joined GIRL'S GOOD LAB (formerly Dentsu Inc. Gal Lab), the industry's first female-focused marketing team. I researched the ever-evolving insights of women and female consumption trends. From 2011, I participated in the Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab. As leader of the "LGBT Unit," conducted Japan's first large-scale LGBTQ+ survey on the challenges facing Japan's LGBTQ+ community and consumption patterns centered around LGBTQ+ individuals. Utilized these research findings to provide strategic solutions and ideas for companies and executives. Official columnist for Forbes JAPAN. Author of 'The Hit-Making Research Guide: Marketing Research Techniques to Boost Your Product Sales' (PHP Institute). Her core belief is: "When the form of LOVE changes, consumption changes."