Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

What Perspective Is Missing Among Those Who Actively Support LGBTQ+ Individuals?

Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab, which researches the field of Diversity & Inclusion (an approach that respects each person's diverse individuality and aims for the social participation of all), conducted a large-scale survey on sexual minorities, including LGBTQ+, titled "LGBTQ+ Survey 2020 " in December 2020.

This article continues from the previous installment, introducing the content of a session held with experts based on the survey results. ( Part 1 is here )

The speakers were Professor Shinichiro Kumagai from the University of Tokyo and Fumino Sugiyama, CEO of New Canvas. Ayaka Asami from Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab served as moderator.

Ayaka Asami: Serves as LGBT Unit Leader at Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab. Active in the LGBT Unit since 2012, she was the lead for the LGBT Survey 2015 and others. Scheduled to publish "The Textbook on How to Create Hits: A Dentsu Inc. Strategic Planner's Guide to Marketing Research That Sells More of Your Products " (PHP Institute) on September 21, 2021. The book will also include content on LGBTQ+ research.

Shinichiro Kumagai: After graduating from the University of Tokyo's Faculty of Medicine, he worked as a pediatrician while living with cerebral palsy. He is currently involved in "participant research" at the University of Tokyo's Research Center for Advanced Science and Technology, studying the relationship between disability and society. He published " The Art of Connection: Neither the Same Nor Different " (NHK Publishing), which deeply examines the difficulties people with disabilities face in connecting with others and the world, and " The Generation of <Responsibility>: The Middle Voice and Participant Research" (Shinyosha), which explores perpetrator-victim relationships and responsibility from the perspective of participant research.

Fumino Sugiyama: Co-representative director of NPO Tokyo Rainbow Pride, organizer of Japan's largest LGBT Pride Parade, and CEO of New Canvas. Involved in establishing Japan's first same-sex partnership system in Shibuya Ward. Former Japanese national women's fencing team member, newly elected director of the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC). Currently dedicated to raising two children as a father, recently published " Trying to Be Parents as a Trio: Mom, Dad, and Sometimes Gon-chan " (Mainichi Shimbun Publishing). His previous book , "Former High School Girl Becomes a Dad " (Bungeishunju) , published last year, also generated significant buzz.

This time, we continue our analysis of the "Cluster Analysis of Straight Individuals' Attitudes Towards LGBTQ+" conducted by Lab members based on survey results.

Among the six clusters, we explore how to interpret the "Active Supporters" and "Naturally Friendly" groups, who demonstrate high levels of understanding, support, and consideration toward LGBTQ+ individuals. We also examine data suggesting that same-sex partnership systems contribute to protecting the human rights of those involved and improving local public opinion. Finally, we present a Q&A session with viewers.

※1 Straight group defined as: Individuals who are heterosexual and whose assigned sex at birth aligns with their gender identity.

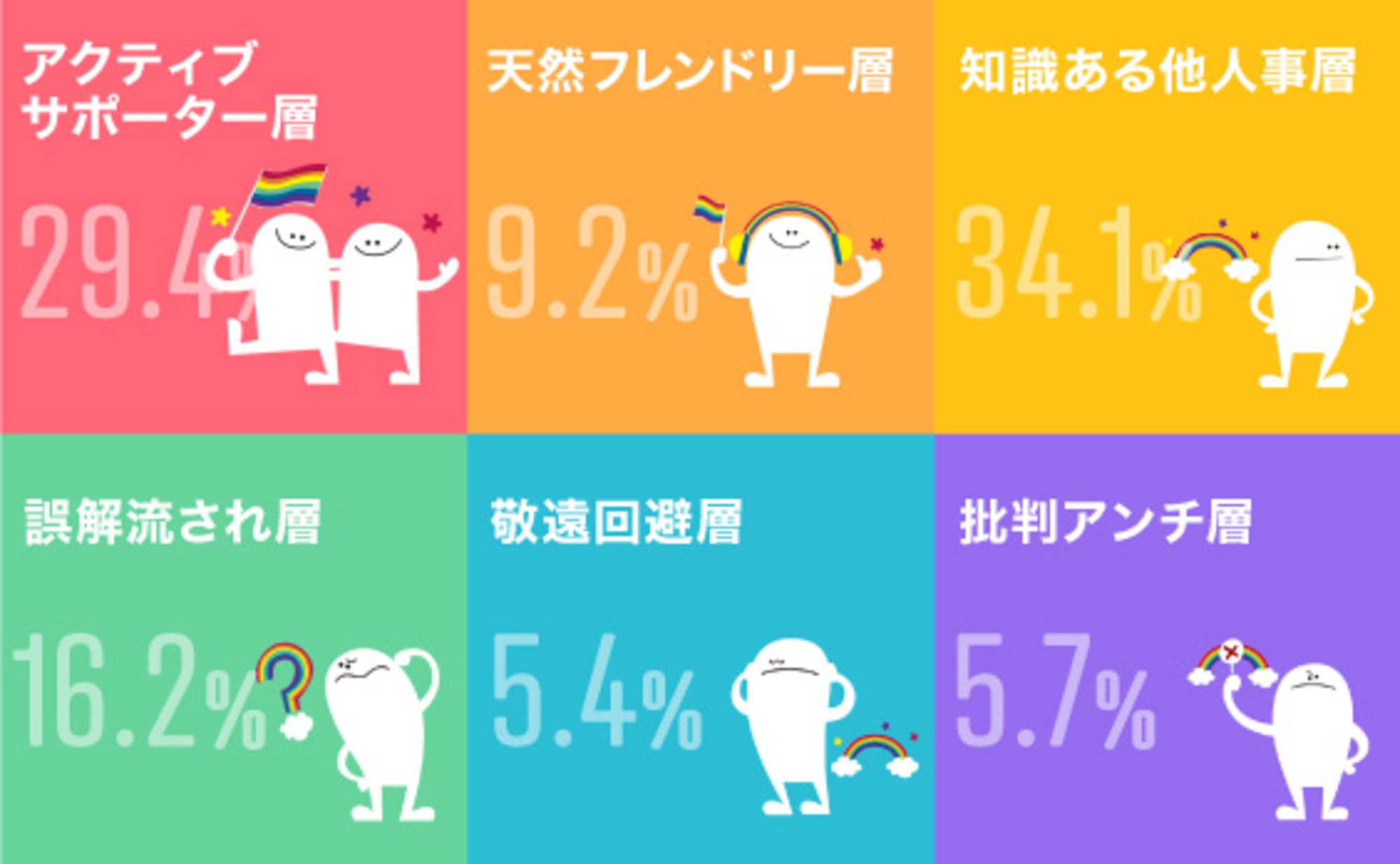

・Active Supporters (29.4%): Highly aware of the issues and actively supportive. Deepened their understanding through personal connections with affected individuals or overseas content.

・Naturally Friendly Group (9.2%): Low knowledge scores but relatively high awareness of issues and consideration, naturally open-minded.

・Informed but Detached Segment (34.1%): Possess knowledge but lack personal connection to the issue (e.g., no close acquaintances affected), resulting in no trigger for awareness. Status quo supporters.

・Misconception-Influenced Group (16.2%): Appears critical due to widespread misunderstandings (e.g., worrying about negative societal impacts like declining birthrates), but fundamentally possesses human rights awareness.

・Avoidance Group (5.4%): They do not actively criticize, but they lack consideration and avoid involvement. They have some knowledge but do not perceive it as an issue.

・Critical Anti-Layer (5.7%): Exhibits strong physiological aversion and significant concern about societal impacts. Also shows disinterest in other social issues like racial discrimination or environmental problems.

See Part 2 of the series for details.

We need to move beyond stereotypes and deepen our understanding of LGBTQ+.

Asami: Regarding the "Active Supporters" and "Naturally Friendly" groups within the six clusters, how should we interpret the data for these segments? Professor Kumagai, what are your thoughts?

Kumagai: The fact that such supportive individuals exist is very reassuring and encouraging data.

That said, returning to the earlier point, this might be overinterpretation—it's not necessarily backed by strong data or academic evidence. Reflecting on my personal experiences, I sometimes think that even among these supportive individuals, some naturally fall into specific categories or dimensions (※2).

※2 The dimension approach is a cognitive framework that views each person as an individual, without categorizing them, and seeks to find common "axes" of empathy between the experiences of different individuals.

In other words, they support people with disabilities based on a certain preconception or stereotype about what a person with a disability is like. While this can be incredibly appreciated in certain situations, I've also experienced it many times before: if I behave in a way that doesn't match the image of a person with a disability that the supporter has in mind, they suddenly feel betrayed. In some cases, I've even faced a bit of hostility.

In that sense, while it might be tempting to interpret the various clusters as if the "active supporter group" is the definitive answer, I suspect that digging deeper with more data might reveal it's not quite that simple. Naturally, people supporting based on categories are included, and that has its pros and cons. I feel we need to examine the data more closely and conduct additional surveys.

Asami: Personally, I also think that was a blind spot. I myself have severe hearing impairment, and I sometimes feel very uncomfortable when professionals like speech-language pathologists or supporters approach me not as Asami the individual, but as someone representing the category of "hearing-impaired people," saying things like, "I really understand hearing-impaired people."

I remember discussing this with Sugiyama-san, and we agreed we must always remember that only the individuals themselves truly understand their own experiences. It really is about each person being different, isn't it?

Sugiyama: Even saying "people with disabilities" covers a wide range of individuals. I'm a transgender person myself, but that doesn't mean I understand everything about transgender people.

A common example is when someone says, "Oh, I know a gay friend, so I get it, I get it." Just because you have one gay friend doesn't mean you understand everything about gay people. It's like someone who's been to Japan once claiming to know everything about Japan – that's just reckless.

Then there's the media. Often, they genuinely have this awareness of the issues and say they really want to cover this topic. But when you actually do the interview, it's "What was the hardest part?" or "What was the most painful?" Ultimately, it often feels like the interview is based on a predetermined narrative: someone who suffered, endured hardship, and persevered to overcome it. I feel that kind of approach also carries a certain risk. So I think it's crucial to truly grasp each individual person.

Asami: We discussed how even well-meaning stigma (*3) might exist among the "active supporter group" and the "naturally friendly group." How did you interpret the data for these groups, Sugiyama-san?

※3 Stigma: A term encompassing phenomena like categorization, stereotyping, prejudice, and discrimination.

Sugiyama: I sometimes wish the "naturally friendly group" could take one more step beyond this "natural" approach.

Lately, I feel like more people are really embracing it in a very positive way. When talking with parents, even those who would say "I support you" a few years ago, if I asked, "But what if your own child were in that situation?", many would respond, "Well, my child is a bit..." But now, they've moved beyond that and say very positively, "No, no, it's fine. If my child were like that, wouldn't it be great if they could live freely?"

What I want to ask next is this: even if they say "Sure, that's fine" when their child is actually in that situation, if their child asks them, "Dad, Mom, why can all my friends get married, but I can't?", what would they answer as a parent?

Would you say, "Well, you're part of a minority, so it's just too bad if you can't be happy. You'll have to endure it"? Or would you, as an adult and a parent, say, "Everyone has equal opportunities, and this is a society where everyone can be happy"? I think what's being asked here is whether we can create that kind of society for the next generation.

So, even if you can positively say "Yes," the reality is that many still can't say "Yes." That's why I really hope people will support—or take some kind of action—toward changing these systems and rules.

The same-sex partnership system can be a catalyst for changing the environment surrounding LGBTQ+ individuals

Asami: Let's move on to our final discussion topic.

This time, we analyzed data from regions with partnership systems and found evidence suggesting they contribute to protecting the human rights of those involved and improving local public opinion. How do you interpret this, Mr. Sugiyama?

Sugiyama: While there hasn't been explicit data in Japan until now, for example, in the US, there's data showing that suicide rates have decreased in states where same-sex marriage is recognized. So, I think it's likely that Japan shows at least some similar trends.

As of April 2021, over 100 municipalities in Japan have implemented similar systems. However, "similar" varies widely: some have established ordinances, others have adopted a "partnership declaration system," some apply to both same-sex and opposite-sex relationships, while others are limited to same-sex couples in the family register. However, regardless of the specifics, the partnership system first launched in Shibuya and Setagaya wards in 2015 inevitably focuses solely on the "partner" aspect.

Of course, partners are important, but what matters most to those involved is the reality of their 24/7, 365-day lives.

The fact that local governments are addressing these issues fundamentally signifies a shift. It overturns the long-held assumption that "people like that don't exist," to the realization that "oh, people like that do exist." I believe this shift in the underlying premise is profoundly significant. Therefore, I hope that data showing how these systems contribute to public opinion will encourage local governments nationwide to actively pursue various initiatives.

Asami: I often hear it said that the same-sex partnership system alone won't solve everything. Still, the gradual introduction of such a system can serve as a catalyst for broader societal change, right?

Sugiyama: Yes. I believe this is a global trend: no place suddenly achieved same-sex marriage overnight. Voices rise up in each region, local governments start changing, and ultimately the nation changes.

While the Netherlands' legalization of same-sex marriage in 2000 seems early, discussions there apparently began around the 1950s. So it took nearly 50 years. I believe this process involves extensive debate, with various initiatives starting in different places, ultimately leading to change across the entire country.

Asami: What are your thoughts, Professor Kumagai?

Kumagai: What you just said really hits home. There are so many situations where systems are designed without considering us.

For example, when I work at my job, I need a supporter. But the current system isn't designed with the idea that there are disabled people in the workplace who need an assistant. That's a reality that causes a lot of hardship. In that sense, the message that this affects all aspects of life really resonated deeply.

Also, within stigma research, stigma is categorized into three types. For example, stigma directed at LGBT individuals by non-LGBT people is called "public stigma," while stigma that individuals direct towards themselves is called "self-stigma." The third type of stigma, which acts as a catalyst for these two, enabling them behind the scenes, is called "structural stigma." This refers to stigma embedded within buildings, social systems, and laws.

I felt the data from this study partially supported and corroborated how addressing structural stigma can positively impact both self-stigma and public stigma.

Looking ahead following the results of the LGBTQ+ Survey 2020

Asami: Thank you. Well, as time is running short, I'd like to hear a final word from each of you.

Mr. Sugiyama, you've actually been advising us since the very first Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab LGBT survey back in 2012 and have co-presented at events with us. How did you find this time?

Sugiyama: Compared to back then, things have truly changed in many ways. The recognition of the term "LGBT" has grown significantly. Looking back, in 2012, we started from points like, "Is that about sandwiches?" "No, that's BLT," "Oh, the light bulb...?" "That's LED." It really makes you realize how much has changed.

But on the other hand, the reality is that there are still mountains of challenges ahead. So rather than just vaguely saying "We're struggling" or "There are so many of us," I think it's crucial to build on solid data and evidence, engage in logical discussions, and move forward step by step. That's why I personally want to make sure I make full use of this data.

Kumagai: In this survey, some respondents cited learning statistics as the trigger for their changed awareness. I found that very encouraging and felt it truly shows how these steady surveys can transform society.

The survey also partially demonstrated the basis for intervening in structural stigma. Furthermore, this cluster survey revealed that when addressing public stigma, a one-size-fits-all strategy likely won't suffice.

While the statistics themselves can certainly help reduce stigma, I also hope we can use them as a compass to explore how we can effectively reduce stigma and discrimination.

By considering whether we hold biases about LGBTQ+ individuals, our awareness and behavior can change.

At the end of the session, we held a Q&A time with the audience. Here are some of the questions raised.

Question 1: I personally have an interest in LGBTQ+ issues and don't think I hold any prejudice. However, I rarely hear others' perspectives, so I thought it would be good to test which group in this survey's results I might be closest to.

Sugiyama: This touches on what's often called unconscious bias. I believe unconscious biases exist in everyone. I'm sure I have them too. It's not that having biases is inherently wrong, but the danger lies in being unaware of them and thinking, "I don't have any biases."

Just because someone is part of a minority group doesn't mean they live without hurting anyone. I don't think that's true. I'm sure there are times when I assume I know something I actually don't, and end up hurting people. So, I think taking tests like this is really valuable.

What's important isn't living thinking, "I get it, I'm not hurting anyone." It's living while constantly being aware that such biases might exist within you. Just that awareness alone will change your perspective and, I believe, alter your words and actions.

So, I suppose just having that awareness is probably a good sign. But if there's an opportunity to take a test or something like that, I think it would be worthwhile to try it.

Question 2: Could you share any positive impacts this pandemic environment has had on diversity and inclusion, as well as any negative effects or future concerns?

Kumagai: My response might lean a bit toward the disability field.

First, regarding positive effects: I recently came across a paper that just came out, and it suggests that, in a sense, everyone has become disabled. Here, "disabled" isn't defined as having a body different from the average, but rather as "people experiencing a mismatch with the current social environment." Because the social environment changed so rapidly due to COVID, some commentators are starting to say that everyone experienced this mismatch and became disabled.

In that sense, the degree to which this is no longer someone else's problem may have increased. However, on the negative side, everyone becoming disabled also means everyone has lost their margin of flexibility.

In such times, the impact of COVID-19 doesn't cause mismatch equally for everyone. Instead, it exacerbates the mismatch for those who were already experiencing it, meaning in some ways, disparities have widened.

In that sense, even if everyone has become disabled, the impact hasn't been equal. Instead, the loss of leeway has made it harder to imagine others' struggles, simultaneously deepening division and inequality. It's a kind of turning point, I suppose. Potentially, there's fertile ground for everyone to unite, but in reality, inequality and division are advancing.

Question 3: I truly feel that the idea of providing proper education from a child's early years is crucial. On the other hand, discussing a child's gender identity or sexual orientation with parents who are already overwhelmed by the demands of childcare might be somewhat shocking. While I believe it's necessary to convey such facts and knowledge, I'd like to hear your opinion on how best to approach this.

Sugiyama: When we talk about education, it's not about lecturing from a blackboard. It's about incorporating it into daily life. For example, there are picture books featuring diverse families, including LGBTQ+ families, though they might be scarce in Japan. There are also coloring books depicting various family types. I think integrating these into everyday life is a good approach.

This isn't limited to LGBTQ+ topics; respecting children's opinions is paramount. So rather than teaching in a rigid way, I think the important thing is to adopt an attitude of thinking together when questions arise. For example, if a child says something like, "Trans people are gross," I don't think it's very educational to just say, "You shouldn't say that!" Instead, ask, "Why do you think it's gross?" and explore it together. Then, when they say, "Because gross things are gross, right?" you can respond, "But why do you think it's gross?" and they might start to think, "Hmmm, why is that?"

Simply saying "no" without helping them understand the essence of the issue will just lead them to repeat similar mistakes. So instead of just saying "no," I think it's better to adopt an attitude of thinking together, or gradually introduce concepts using picture books or other accessible formats. I hope you can take it step by step, starting where you can, without overcomplicating things.

After the Webinar

Through this webinar, we've explored the LGBTQ+ survey alongside Professor Shinichiro Kumagai and Fumino Sugiyama.

While the largest segment of Japan's straight population is the "informed bystanders," all social issues are interconnected. There is no issue that can truly be considered "someone else's problem." Not just for LGBTQ+ issues, but especially for those we might think "don't really concern me," each individual must recognize that they might be the privileged party regarding that issue and could be contributing to the structures causing hardship. It's from this awareness that society might begin to change for the better. Within each of the six clusters, there are both "category types" and "dimension types," each requiring effective approaches. Approaching "structural stigma" (the stigma embedded in buildings, social systems, laws, etc.), which acts as a catalyst for both "public stigma" and "self-stigma," brings us closer to a fundamental solution. Delving deeper into this data provided many insights.

The LGBTQ+ survey has been conducted repeatedly in 2012, 2015, 2018, and 2020. Guided by the hope that it will serve as one opportunity for society to learn about, engage with, and consider LGBTQ+ issues, Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab will continue analyzing the survey and taking action.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Ayaka Asami

Dentsu Inc.

Second Integrated Solutions Bureau

Strategic Planner

As a strategic planner, I have been involved in marketing, management strategy, business and product development, research, and planning for numerous companies. In 2010, I joined GIRL'S GOOD LAB (formerly Dentsu Inc. Gal Lab), the industry's first female-focused marketing team. I researched the ever-evolving insights of women and female consumption trends. From 2011, I participated in the Dentsu Inc. Diversity Lab. As leader of the "LGBT Unit," conducted Japan's first large-scale LGBTQ+ survey on the challenges facing Japan's LGBTQ+ community and consumption patterns centered around LGBTQ+ individuals. Utilized these research findings to provide strategic solutions and ideas for companies and executives. Official columnist for Forbes JAPAN. Author of 'The Hit-Making Research Guide: Marketing Research Techniques to Boost Your Product Sales' (PHP Institute). Her core belief is: "When the form of LOVE changes, consumption changes."