Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

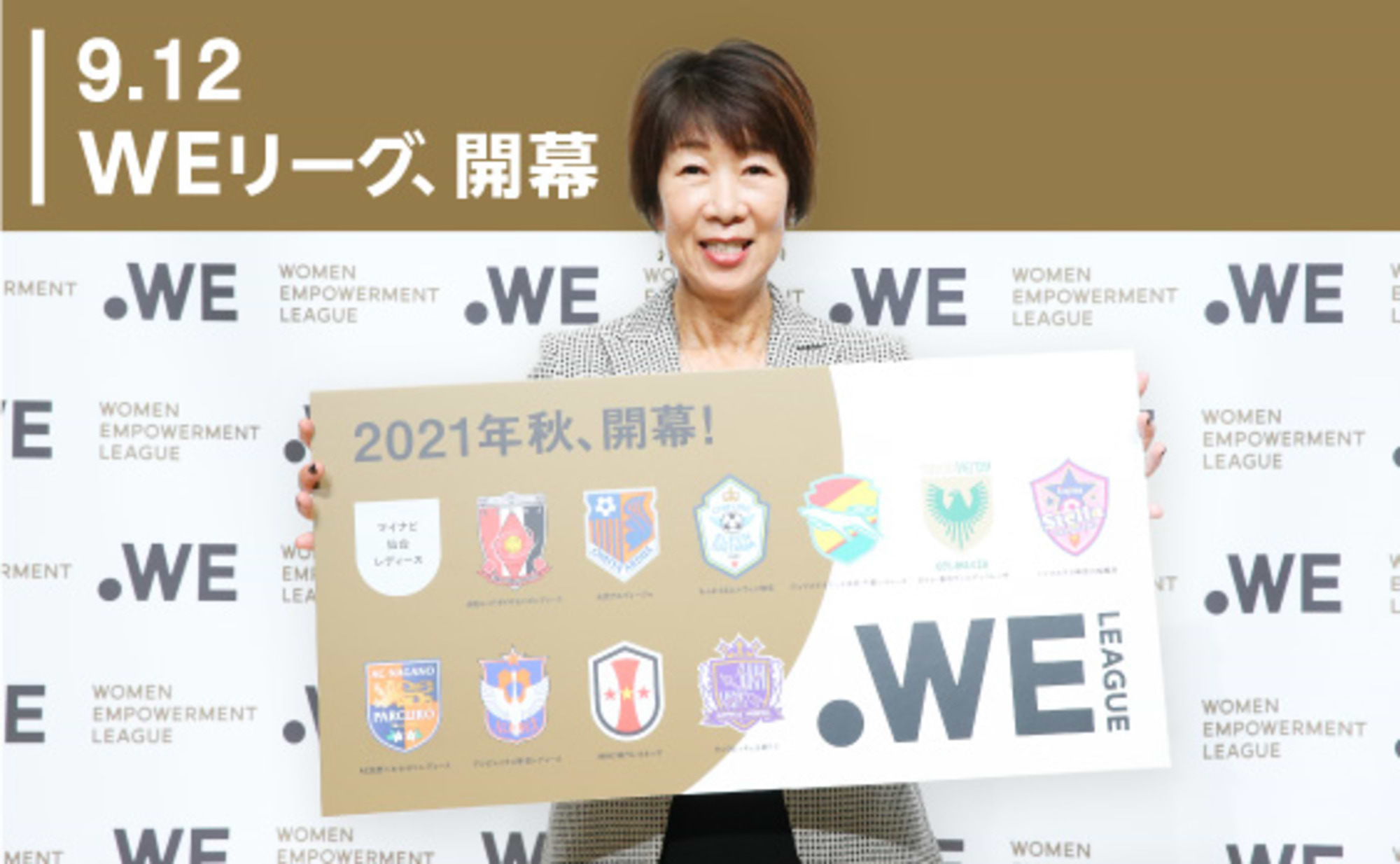

9.12 WE League Kicks Off

The profession of "women's soccer player" is finally born in Japan!

Japan's first professional women's soccer league, the WE League, kicks off on September 12. WE (meaning "everyone") aims to realize various forms of women's empowerment in society through soccer. We spoke with Chairperson Kikuko Okajima and Akane Nakakura, Marketing Department Manager, who support the league.

──I understand both of you played soccer. Why did you choose soccer?

Okajima: Because it's fun to play and fun to watch. When I started playing soccer, there was a TV program called "Mitsubishi Diamond Soccer" that broadcast soccer matches from Europe and elsewhere. I found soccer incredibly appealing—I felt there was no sport more exciting. I was naturally athletic, so playing soccer among boys never felt strange. I never felt like I couldn't kick or run well, which is why I played.

Nakakura: Players fighting while carrying everyone's support on their backs are so cool! At the first J.League match my parents took me to, the supporters' passion and the sound of their cheers—seeing players fight while carrying that support looked incredibly cool. At that moment, there was no gender divide. I thought, "I want to be like that!" "I want to start playing soccer!"

Nakakura: If the first match I saw had featured "women's soccer players," I might have truly embraced it as my future dream and kept playing soccer all along. Honestly, when I got to high school, I realized that being a "soccer player" wasn't a realistic career path. That's why I hope the WE League will mean more girls like me won't give up halfway, but instead keep aiming to be professional "soccer players" right to the end.

──What challenges did you face playing soccer?

Nakakura: In junior high, I was the only girl. I couldn't play in matches. Occasionally, when I did play in practice games, the opposing team's coach would say things like, "Go for the girl on the wing over there." It was frustrating. Since I was the only girl, there was no changing room, so I had to change clothes inside my own clothes. Why didn't I think about quitting? I think it was purely because I loved soccer and thought soccer players were cool. I wanted to be like them.

In high school, I happened to find a girls' soccer club. It was 2011, right after Nadeshiko Japan won the World Cup, a time when awareness of women's soccer and the number of clubs were growing. I really felt firsthand how the success of the top level impacts the expansion of the sport's base. While I distanced myself from competitive play after high school, that's precisely why I want to create environments where many girls can experience and play soccer.

Okajima: The first major hurdle I felt was when we participated in an international tournament hosted by the Asian Football Confederation in 1977. We went to Taiwan as FC Jinnan, an independent team. Back then, women weren't considered part of the game, so we weren't registered with the football association.

Even though we represented Japan, we couldn't wear the Rising Sun emblem on our chests, so we wore it on our sleeves instead. Countries like Singapore and Thailand had national teams, so why didn't Japan? This became the catalyst. After returning from Taiwan, I decided to create a Japanese national women's team. Two years after the Taiwan tournament, when I was a sophomore in college, I founded the Japan Women's Football Association.

Of course, I didn't create it alone. At the time, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries had a women's team, so with their support, the Women's Football Association was born, centered around Mitsubishi, and I became a founding board member. In its first year, 1979, there were 51 registered women's teams, totaling just over 900 players.

Another major challenge was the lack of proper fields. There were no changing areas on the riverbanks. We either rode the train home covered in mud or took turns changing inside a single bath towel held by three people.

Toward a League Realizing "Gender Equality," "Women's Empowerment," and "Everyone as Protagonists"

──The WE League is Japan's first professional women's soccer league. Could you tell us what kind of league it is?

Okajima: For about 30 years, there was an amateur league called the Nadeshiko League. Within that, only a dozen or so players had professional contracts. The rest played soccer as amateurs while holding down jobs. Starting this year, however, 250 WE Leaguers have emerged, making "women's soccer player" a viable profession.

As a sports league, its defining feature is its clear articulation of social significance. When the J.League started, it also aimed to make sports a cultural cornerstone. The WE League, however, specifically targets "gender equality" and "women's empowerment."

Nakakura: The WE League upholds the philosophy that women's soccer, through sport, contributes to realizing and developing a society overflowing with diverse dreams and ways of life, where each individual shines. The league name and philosophy were created with the intention of being a league that empowers women, while also directing an arrow from women and the WE League outwards towards society, aiming to turn the whole of society in a positive direction. We believe it is crucial to drive this social significance forward on two fronts: not only as a soccer league and soccer business, but also encompassing its societal aspects.

──What specific actions or activities are currently planned?

Okajima: First, we set a club entry requirement that 50% of staff must be women. Furthermore, we mandate that at least one woman must be included among decision-makers like executives and directors. Including at least one female coach or manager is also part of the entry criteria. We incorporate a female perspective into match venues, such as providing childcare facilities.

Furthermore, the WE League has a Philosophy Promotion Department within its secretariat, and we require each club to appoint a Philosophy Promotion Officer. Since 11 clubs compete in the league, one club is always on a break. That club focuses on philosophy promotion activities: players take the lead in engaging with the local community to identify issues, and initially, this might involve teaching soccer to elementary or junior high school students.

We also created the WE League Credo together with the players. It defines our code of conduct in the players' own words. Initially, it stated, "We play for one girl." But through repeated meetings, the players realized it wasn't just about one child or girl—there are adults, men, and boys too. So it evolved into "We play so everyone can be the protagonist." Through this ongoing discussion, the players' awareness continues to evolve. As you can see from our social media posts, we're already seeing the results of this.

Together, we want to create collective impact

──Through the actions mentioned in Chairperson Okajima's remarks, what kind of movement do you want to create?

Nakakura: We'll be conducting social activities under the name "WE ACTION." Beyond the "WE ACTION DAY" events where the club and players promote our philosophy, we plan to hold "WE ACTION MEETINGS" with our partner companies. These meetings will help us understand social issues and brainstorm solutions. As the WE League, we aim for this to become a platform where players, the club, the WE League, and partners inclusively join hands side-by-side, expanding our circle and building social power.

──What do you think is the appeal of soccer, in a nutshell?

Nakakura: You can start with just one ball. The rules are relatively simple, making it easy for newcomers to watch. Globally, the large number of people who play is also a major appeal.

Okajima: From a playing perspective, handling the ball with your feet isn't something you do much outside of soccer. You get better and better at it as you play. And kicking the ball with your feet feels incredibly satisfying.

Another aspect is soccer's tactical element. Like in shogi, you think two moves ahead when passing. You consider how your play will shape the flow—for instance, passing to this player makes a cross easier—and make decisions based on your own judgment (not just following the coach's instructions). I think this is a major appeal of soccer.

──What are you looking forward to or paying attention to as the season approaches?

Okajima: One is the foreign players. We'll introduce seven of them on September 12th. To aim for the world's best as a league, we want top players from overseas. While we don't have any hugely famous names yet, players at the national team level from their countries are coming. I think this is a bit different from the previous "Nadeshiko League."

Another is our initiatives with partners. Yogibo is our title partner, and starting with the opening match at Noevir Stadium Kobe, we'll place Yogibo cushions right next to the players, creating "grass-front seats" instead of the traditional sand-front seats.

Additionally, we're creating a Sensory Room. For families with children who have developmental disabilities—for example, those who feel scared in unfamiliar crowds or react to bright lights and loud noises by shouting—we'll invite two families at a time to a soundproofed room at Noevir Stadium Kobe. They can relax on Yogibo cushion seats and enjoy the match comfortably. While the focus shifts to soccer once the game starts, I'm also very much looking forward to each club's initiatives promoting their core values.

Various collaborations with partner companies

Nakakura: This season, X-girl is providing uniforms as the official supplier for seven clubs. Even for those who haven't been interested in soccer before, there are different ways to deliver information, like through fashion-related messaging, so we hope people will pay attention to that too. And of course, once the season kicks off, the performance of the soccer league itself is a highlight. We hope the WE League can deliver the players' positive energy to everyone.

──How do you want to convey the power of sports?

Okajima: On the soccer side, we want to increase the number of girls playing soccer. Naturally, we want them to see players performing right before their eyes. To get people to come to the stadium, we want to create opportunities for them to interact with players through soccer schools and philosophy promotion activities.

Regarding the players themselves, I want to establish clear paths for their careers after retirement. For example, we've set up a system where JFA instructors are dispatched to clubs, allowing players to obtain their C-level coaching license without having to travel anywhere. With such a system in place, players can earn their B-level license during their playing careers and then immediately pursue their A-level license after retirement, enabling them to become coaches in the Nadeshiko League.

Furthermore, more countries are embracing women's soccer. I hear Japan, a pioneer in women's soccer, receives numerous requests to dispatch coaches. We envision retired players spending several years in Asian countries as coaches, promoting soccer and helping strengthen the sport there. For the players themselves, living in a completely different country for a few years would be an incredibly valuable experience, so we are working to establish this pathway.

A path for women to live their lives alongside soccer

──Please share a message for the future of the WE League.

Okajima: I want to see lots of women coming to the stadiums. In the US, families make up the biggest crowd. That's why the cheers are so loud and high-pitched. When you go to a Nadeshiko League match, it's still mostly men in their 30s to 60s, so the cheers are very low-pitched.

I want to create a stadium atmosphere filled with women, children, and families, where louder cheers become more common. To achieve this, having non-soccer content at the stadium is also crucial. For example, I want stadiums to offer food, clothing, and events that children can enjoy.

Nakakura: I believe the WE League must constantly aim and think about continuing for 30, 50, 100 years. Otherwise, it won't become a league girls aspire to join. While it's a sports league, it bears the name WE (Women Empowerment) League, right?

"Women Empowerment" is often translated as "women's advancement," but I don't feel that phrase quite fits. At the WE League, we want to convey that gender equality isn't about girls or boys, but about seeing each individual person. We want to create a society where "Women Empowerment" doesn't automatically translate to "women's advancement" in Japanese. As the WE League, we aim for a future where Japan changes so much that society itself wonders, "Why did they even name it 'WE' in the first place?"

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Author

Kirillova Nadezhda

Dentsu Inc.

Business D&A Division Team B

Creative Director

Born in Leningrad, USSR (at the time). Raised in six countries. After joining Dentsu Inc., worked as a creative across diverse fields, handling a wide range of domestic and international projects. Recipient of numerous awards. Member of the Active Learning "How About This?" Research Institute.