As the COVID-19 pandemic subsides and international travel begins to increase, circular economy study tours to the Netherlands by Japanese companies are booming.

This time, we interviewed Ryuichiro Nishizaki, who coordinates circular economy tours while residing in the Netherlands, and Shinichi Noguchi, who supports Japanese SMEs from the Netherlands.

We asked them about the reasons behind the success of the circular economy and startup communities in the Netherlands, and what Japanese companies are bringing back from the Netherlands. The interviewer is Rie Tanaka from Dentsu Inc.'s Sustainability Consulting Office.

Mr. Noguchi (left) and Mr. Nishizaki (right)

The concept of treating events as "living labs" and scaling them to the city

──First, could you tell us the background that led you to live in the Netherlands and start a business targeting Japanese companies?

Nishizaki: I belong to Japan Grey Line, a company specializing in events and tours. While on parental leave, I happened to learn about the Netherlands' sustainability initiatives. I thought these initiatives could solve the vague concerns about sustainability within the event industry. So, I researched "Sustainability × Events," wrote a new business proposal, and presented it to the president. It was approved, leading to the creation of a Sustainable Business Division as an internal venture. This involved developing an approach specifically tailored to the event industry in the Netherlands.

──Specifically, what kinds of events are unique to the Netherlands?

Nishizaki: The most famous is the music festival DGTL. It's a large-scale event, comparable to Fuji Rock or Ultra Japan in Japan, and it became the world's first circular event. I was shocked to learn that an event could be zero-waste!

DGTL Event Scene

Nishizaki: Events involve various industries. It's not just entertainment; it includes food, architecture, transportation, and more. It's like a small city.

In the Netherlands, there's a concept of running events as "living labs" (places that replicate living spaces and develop new technologies and services with resident participation). The idea is that if it works well, you can scale it up to the city level. I strongly believed this approach should be brought to Japan. I wanted to ensure that when Japanese companies pursue SDGs, events aren't just an afterthought. Instead, I wanted to use events as a way to drive sustainability forward.

──What prompted you to start your current business, Mr. Noguchi?

Noguchi: I only arrived in the Netherlands in April 2022. While I primarily support Japanese SMEs, I also assist Dutch companies considering expansion into Japan or Asia with business planning and market research.

After becoming independent in 2018, I worked as an advisor for local governments in Japan and supported SMEs in launching new ventures. During my corporate career, I was responsible for business development, including establishing overseas bases and M&A. When considering how to revitalize regional areas, I felt looking overseas opened up various business opportunities. However, moving from a regional area to overseas presents high investment hurdles. I thought that if I moved myself, I could make it feel more accessible.

──Why the Netherlands?

Noguchi: I chose the Netherlands because I wanted to move to a slightly less common country. When I arrived, I found people like Mr. Nishizaki were already there. Going forward, adapting to the circular economy is essential, so I decided to connect Dutch circular economy initiatives with Japanese companies.

──What kind of needs exist for work connecting the Netherlands and Japan?

Nishizaki: For sustainability study tours, some come for internal training and input, while others come to influence their business partners. When pushing new projects, traveling together can deepen trust. It's not just people with high interest; sometimes those who aren't particularly interested in sustainability or the circular economy but feel they must engage also come.

The range of industries is broad, from local governments and universities to consulting firms, manufacturers, and architecture/urban development. Dutch regulations on construction waste and related solutions are particularly advanced within the EU. We also have design projects underway in Japan with Dutch designers.

Noguchi: I often get requests to find partners for expanding services in Europe. Beyond that, it's less about specific industries and more about young SME owners in their 30s and 40s looking for insights on food, urban development, and regional revitalization to grow their businesses. They often turn to .

"The Netherlands was built by the Dutch" – Dialogue-focused education without report cards

──Why is the circular economy so advanced in the Netherlands?

Nishizaki: There's a saying in the Netherlands: "God created the world, but the Dutch created the Netherlands." This is also a historical fact; essentially, they built their land through land reclamation. Windmills were originally built to drain water, and cities like Amsterdam and Rotterdam were literally dams. A quarter of the country lies below sea level, and its history of battling floods means it faces the threat of sinking if sea levels rise due to climate change and warming. This has fostered a high level of climate change awareness.

The Netherlands has a population of about 17.5 million, roughly the same size as Kyushu, making it a small country. Yet, it is home to people of very diverse nationalities. One theory suggests that precisely because the population is so diverse, they prefer things that are not only in language and writing but also in design that are simple, easy to understand for everyone, and highly functional. As seen in what's called Dutch Design, they're also skilled at presentation. This approach extends beyond products to policy and other soft aspects, leading to "designs that are understandable and convincing for everyone."

Noguchi: I feel the history of the Netherlands, shaped by the Dutch themselves, of cooperatively creating livable spaces, connects to the social nature of the Dutch people. For example, listening to the teachers at my son's elementary school, they emphasized dialogue while assuming differing values and backgrounds, valuing everyone standing on the same playing field. Perhaps things difficult to advance in the Netherlands due to various economic interests and other factors move forward precisely because of this attitude of dialogue.

Schools strictly avoid comparing children. There are no report cards, and even if tests are given, results aren't shared with the children. They respect each child's pace and what they want to do. Even in elementary school, if a child struggles to keep up with lessons, they can choose to repeat the year. Those who understand the material teach those who don't, regardless of age. Repeating a year is met with comments like "Good decision," fostering mutual respect for individual paces. Timing for entering the workforce isn't uniform either.

Dutch Elementary School

──That's wonderful education. Conversely, are there things that are difficult to do in the Netherlands or things you have to be careful about?

Noguchi: Dutch people will abruptly cut ties if they see no personal benefit. If they lose interest, they might stop responding altogether. I appreciate how straightforward they are.

Nishizaki: When we do tours, we sometimes hear that "Japanese people follow the 3Ls: Look, Learn, Leave." They see, learn, and just leave. The Dutch seem to feel that neighboring Asian countries offer greater economies of scale than Japan. We sometimes hear complaints from the Dutch that when Japan only asks to "learn," it rarely leads to subsequent projects. This means opportunities for Japanese people to keep learning are also lost. That's why we provide support after returning home, aiming not just to learn, but to connect it to future business opportunities.

The product with the design you wanted turned out to be sustainable

Dutch supermarket (vegetable section without plastic packaging)

──What kinds of places foster circular economy businesses in the Netherlands?

Nishizaki: I'll share insights based on a recent inspection trip to the Netherlands by Funabashi Corporation. Funabashi is a company providing total solutions for spatial creation and has gained attention as an industry leader in creating spaces through ethical design. This visit aimed to experience facilities implementing Europe's cutting-edge and unique ethical design practices to incorporate them into Japanese facility planning.

Furnify is a circular space design company. At " DB55," an office, coworking space, and showroom they designed, furniture and building materials are reused not as second-hand items, but as "second lives" – repurposing items destined for disposal. This approach offers high design quality, convenience, and storytelling potential. Each material has a two-dimensional barcode that tells its story. For example, the black tiles covering the floor are instantly recognizable to Dutch people: "Those are the train station tiles, right!?"

Scanning a chair's code reveals it was used by an actor on a famous TV show during filming. This storytelling can multiply the item's inherent value many times over. When clients visit, even those who previously lacked a tangible sense of value instantly grasp the concept, leading to rapid progress in negotiations.

Sustainability is integrated right from the design phase, making the space very rational. During actual site visits, participants not only hear presentations but also tour the facility, leading to deeper understanding. We hope this inspires them to apply insights to their businesses in Japan, and potentially even leads to collaborations.

Scene during the inspection (Provided by Senba Co., Ltd.)

Noguchi: Rotterdam's " Blue City " is a former swimming pool. It houses offices and coworking spaces for startups involved in the circular economy, while still retaining elements reminiscent of a pool. Here, practical information like product ideas and grants is actively discussed.

Noguchi: Starting a startup alone can be lonely, but being part of this community provides reassurance. It also fosters lateral communication, like "We can do this part by applying for that grant." Even when you can't realize an idea alone, you find people willing to pitch in.

Nishizaki: What's distinctive is that information isn't just shared—it circulates within Blue City itself. For example, Company A's waste heat is used by Company B to create something, and the CO₂ emitted from that process is then used to grow plants. This ecosystem naturally generates projects.

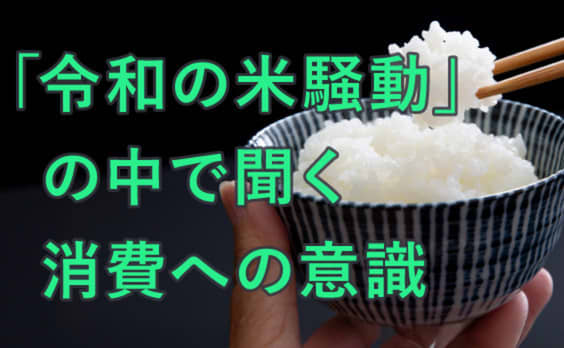

──Is the circular economy rooted among citizens not just in companies and startups, but also in consumer behavior?

Noguchi: What surprised me compared to my preconceptions was that, rather than having a dedicated "Circular Economy" section in stores, the products sold in supermarkets and shops were fundamentally designed with this principle in mind. They're just displayed normally, and if you see something appealing, it's likely already circular economy-conscious. I was amazed by how deeply ingrained this is in the Netherlands – these items aren't treated as special, they're just part of everyday shopping.

──Aren't the costs high?

Noguchi: They're not outrageously expensive. First, you like the product, and then you realize it's sustainable.

Nishizaki: Design comes first. Customers choose them because the design is cool and they're convenient. If you retrofit existing products with sustainable materials, costs would likely go up. But here, sustainability is built into the design from the start. Some brands also reduce unnecessary processes and materials to lower costs, making their prices comparable to regular products.

Young people's high engagement with environmental and political issues stems from "doing it while having fun."

Mr. Noguchi (left) and Mr. Nishizaki (right)

──Are there differences in politics and legal frameworks compared to Japan?

Nishizaki: Amsterdam's current mayor comes from a party strong on environmental issues and has gained support from environmentally conscious young people. It might be hard to imagine in Japan that pressure from young people in environmental groups, pushing aside industry, could change politics. They monitor and disclose the degree of circular economy implementation and adjust tax systems. However, I've heard that striking the right balance is crucial because if regulations get too tight, companies will leave.

Shell, originally a Dutch company, lost a court case to environmental groups and was ordered to reduce CO2 emissions by 45% by 2030. This prompted them to relocate to the UK. Being environmentally friendly isn't always the only right answer, is it?

There's also active discussion on how to reshape incentives for companies to engage with the circular economy. To sustainably use resources, we need a reverse economy that regenerates them. This involves multiple human steps and costs, making it more expensive than using virgin materials. Therefore, discussions are underway about taxing raw materials. For example, with concrete, the idea is to tax virgin materials so recycled and virgin materials cost the same.

Furthermore, about two years ago, plastic waste, which had previously been sorted as general waste, became combustible waste. The reason is that citizens don't sort it properly, so it's more efficient to separate it mechanically at the plant after collection. So, rather than Dutch people having particularly high environmental awareness, the system itself is solving the problem.

Noguchi: I feel education forms the foundation for young Dutch people's interest in politics. Creating opportunities for children to think, like "I enjoyed lessons about what's good and bad for the Earth," and fostering environmental education that encourages voluntary action is crucial. It's a process taking decades, but the Netherlands excels in this area.

They approach the circular economy not as a rule, but as entertainment—experiencing it enjoyably, then changing their actions from there.

Nishizaki: The Netherlands can be called both a "pioneer in challenges" and a "pioneer in embracing failure." It seems they've now moved past the initial challenge phase and entered a period of scaling up from prototypes. This presents an opportunity for Japanese businesses to collaborate and leverage the momentum of Dutch sustainability growth to scale up their own initiatives. Japan possesses excellent technology, but I believe we can learn from the Netherlands in branding and creating commercial channels. That said, rather than viewing it as "the Netherlands = amazing" versus "Japan = still has a long way to go," if we can advance together, wouldn't we be able to leverage each other's strengths more effectively?

Noguchi: Many business leaders operate not just for their local areas but with a desire to improve Japan as a whole. That aspiration drives them to pursue new challenges. Even brief exposure to the Netherlands, now entering its scaling phase, could be stimulating and shift Japan's mindset. After all, growth through absorbing and adapting from abroad is one of Japan's specialties.