Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

The Unleashed Japanese (Part 1) ~ The Breaking Point Where the "Defense Instinct" Breaks Down ~

In this series, members of Dentsu Inc.'s new consumer research project "DENTSU DESIRE DESIGN (Dentsu Desire Design: hereafter DDD)" introduce consumer insights and approaches rooted in "desire."

<Table of Contents>

▼Introduction

▼Apologies for jumping straight to a conclusion-like discussion

▼"The Real World Raised to a Higher Level" Breaks the Restraints

▼"Motivation with Nowhere to Go" Breaks the Restraints

Introduction

What is the image of the Japanese people? Overseas travelers often describe them as "punctual," "diligent," "meticulous at work," "polite," and "kind" in interviews and such. These impressions largely align with the self-image Japanese people hold of themselves and represent virtues many Japanese aspire to embody.

However, in recent years, many people likely feel that events challenging these images have become increasingly common. Excessive online bashing occurring almost daily, runaway righteousness, ever-expanding cravings for approval, scandals sparked by all too easy breaches of morals and rules, the existence of the so-called nuisance genre, and so on. How should we interpret these "un-Japanese" occurrences? In fact, surveys over the past few years also show data indicating that Japanese people are gradually losing their sense of pride in being Japanese.

Therefore, in this analysis , we will proceed with the hypothesis that "the Japanese temperament may have changed with the times" and explore its verification. This perspective also suggests that behind these behaviors—which are contrary to the essence of Japanese identity and often not what people themselves desire—may lie the influence of larger forces of the era and society.

Apologies for jumping straight to what might seem like a conclusion

The keyword that emerged from this examination, as reflected in the title, is "Japanese people who have lost their restraint." In other words, precisely because they were originally restrained, moral, patient, and sometimes even more respectful of others than themselves, the moment they exceeded their limits of endurance, the reaction became significantly more extreme.

Incidentally, "taga" (箍) refers to the rings fitted around the outside of barrels or casks to hold them tightly together. When the taga comes off, the barrel or cask falls apart. Therefore, saying "the restraints came off" often carries a very negative connotation. However, what's crucial here is not a self-initiated, proactive act of "removing the restraints," but rather the part where external factors pushed them beyond their limits, causing the restraints to come off. In that sense, what triggered this situation could perhaps be seen as a kind of defense mechanism.

Living in a restrained, moral, and patient manner, sometimes prioritizing others over oneself. It seemed that, driven to the point where such composure vanished, people chose to vent pressure to protect themselves before their vessel—themselves—shattered (even if most did so unconsciously).

So, what were the external factors that pushed the Japanese people to this point? I would like to highlight three major ones. First, Japan's prolonged economic stagnation. Since 1998, both nominal and real GDP have declined, and wages have continued their downward trend. Alongside the loss of pride as an economic powerhouse, the stark realization that "we are no longer affluent" has become increasingly palpable in daily life. This suffocating feeling of struggling desperately yet being unable to break the surface is, I believe, one major factor driving Japanese people to the brink.

Next, adapting to drastically shifting values. Over the past few decades, long-held fixed values regarding gender differences, human rights, the global environment, and work styles have undergone rapid and significant change. Adults struggle to update deeply ingrained values, while young people spend their days frustrated by the reality that new values don't immediately permeate society as a whole. Debates over what is right and wrong tend to become heated, and one wrong step can easily spark a social media firestorm, making it impossible to relax.

Finally, technological evolution. The advent of social media, in particular, had a massive impact. While the democratization of information is undeniably positive, it has also brought new-age struggles: things we could previously ignore are now visible, and we face the difficulty of distinguishing between misinformation, like fake news, and accurate information.

These three external factors permeate our daily lives constantly, leaving no escape. Therefore, whether we're conscious of it or not, we continue to be affected little by little every day. Small stresses accumulate drop by drop, steadily filling the cup.

And then came the pandemic, pouring not just a drop but a ladleful of water into a cup already brimming to the edge. The impact shattered the small joys we had carefully guarded in our daily lives. Furthermore, the reality unfolded where, despite uniting with the kind of proactive public health response typical of the Japanese, we were eventually overwhelmed, leading to numerous sacrifices.

The intense polarization over masks likely stemmed partly from a sense of powerlessness. Despite no legal mandate, everyone simultaneously curtailed outings, emptying the streets. People persevered, wearing masks even indoors, not just for handwashing. This very discipline, I believe, fueled distrust and stress toward what was seen as "typically Japanese restraint." "Accurate," "diligent," "meticulous," "polite," "kind"—these traits feel burdensome and meaningless. It's perhaps inevitable that more people began thinking this way.

Moving forward, I'd like to explore from four perspectives the specific situations where people exhibit "unrestrained" behavior. In this first part, I'll introduce two concrete examples.

The "Elevated Reality" That Breaks the Restraints

Take digital photo editing, for instance. These days, unedited photos seem rare among young people. Make eyes a bit bigger. Legs slightly longer. A subtle face-slimming touch. These functions are built right into camera apps, allowing anyone to effortlessly and automatically retouch their face or body.

Even in an era where active discussions about lookism are common, the pressure to be cute or cool still bombards people through their smartphones. Everyone, regardless of gender, tweaks and retouches a little. Seeing these photos flood in daily naturally makes people feel rushed.

The experience of editing often starts with photos taken by friends on their phones, or simply out of curiosity when you try an app yourself.

"Is this too much? But maybe it feels a little good?" The ability to alter even parts that can't be changed in reality makes even small adjustments feel like they have a big impact. Therefore, it's no wonder that once you experience it, you start to feel uneasy about leaving things untouched. It's similar to the psychology of how, as children, we lived with our bare faces, but once we start wearing makeup, going out "bare-faced" feels embarrassing.

So, what happens when you post that photo on social media? There are those so-called "miracle shots" – photos that just happen to turn out exceptionally well. Naturally, such a shot garners more compliments than usual, like "You look cute!" or "You look handsome!"

Being able to edit photos means you can mass-produce these "miracle shots." It's no surprise then that about 60% of people in their teens to 50s edit photos primarily to send to others or post on blogs and social media.

This creates a daily reality where "slightly edited photos flood the streets." In such a society, even if reality differs, the illusion arises that the world is full of cute and handsome people, fueling lookism and feelings of inferiority. Consequently, this also fuels the desire to "enhance even more."

What started as just a subtle touch-up gradually evolves into a comprehensive enhancement of one's appearance. Especially with anonymous accounts, where the edited image reaches people who don't know the real you, the degree of editing becomes harder to discern. Ironically, the more drastically altered the image, the more it might even offer the advantage of obscuring the original self.

Thus, it becomes normalized for society as a whole to constantly carry around a self that diverges from who they truly are. When others give "likes," the self that receives the validation is the embellished version, creating a sort of split personality situation. It's the ideal self, the self that's being praised, yet it's not the real self. Doesn't the concept of "self" gradually become unstable?

It becomes impossible to know where one's core self lies. What even is "me"? In such a state, anyone can lose the balance of their self-image from the slightest trigger. It's entirely plausible that people might lose control, trying desperately to "process" themselves to make things fit—like seeing overly large eyes in photos as "normal" or repeatedly undergoing excessive cosmetic surgery. Additionally, the mental impact, such as body dysmorphic disorder where people obsess over barely noticeable flaws in their appearance, is starting to gain attention recently.

Everyone cares about their appearance. Very few people are extremely confident about their looks. In fact, more people likely have complexes. The emergence of new technology has rapidly normalized photo editing. I want to keep watching how this societal shift will influence people's consciousness going forward.

【Desires That Catch Your Attention】

→ "I know it's wrong, but still..." desires

→ "Desires reflected in the mirror of others"

※For DDD's analysis of the new "11 Desires," see here

"Motivation with nowhere to go" breaks free

Japan's GDP, which fell to third place globally after being overtaken by China in 2010, dropped to fourth place in 2023 after being surpassed by Germany. For the Japanese, known for their diligence and patience, steadily accumulating effort, the anguish of "Why did this happen?" is predicted to intensify further.

Even young people, who should be envisioning various future possibilities, find themselves in a situation where they have absolutely no hope for the future. This situation in our country stands out significantly compared to the rest of the world, with only about one in ten young people imagining a bright future.

https://www.nippon-foundation.or.jp/app/uploads/2022/03/new_pr_20220323_03.pdf )

Japan's economy has been in a prolonged slump, often referred to as the "Lost 30 Years." Yet, if asked, "Have the Japanese been lazy during this time?" the answer is clearly no. They have worked desperately and strived daily. So why has this effort gone unrewarded? Why is Japan alone being left behind by global growth? Something is wrong. What is going on? It's only natural to think this way.

For generations who remember Japan's prosperous era, epitomized by the high-growth period, this sense of dissonance is particularly profound and impossible to ignore. The belief that maintaining typically Japanese work habits – punctuality, diligence, meticulousness – would lead to a better life is rooted in past success. This makes the current prolonged stagnation unbearable. Faced with companies plunging into the red from a single stock or currency fluctuation, the immense damage from recurring natural disasters, and the sheer injustice of crises like the pandemic, it feels like no amount of effort matters anymore.

To take that next step forward, people crave a reason. They want to know why first. As more people feel this way, it becomes visible and networked online. This is the first step in what's often called the "conspiracy theory" phenomenon.

One day online, you encounter something "astonishing," "unknown to anyone else," or a "shocking truth." "Was it my fault?" "Is some greater force at work?" "Are we all being deceived?" Even while still half-doubting, it feels like the reason you craved is right before your eyes. Even when someone counters, another person offers answers or new possibilities. These accumulate, and the force of wanting a reason builds into a powerful wave that constructs a worldview, solidifying a robust conspiracy theory world.

As shown in the figure above, only about 40% of people can immediately recognize misinformation as false upon encountering a conspiracy theory; one in four believes it to be accurate. Furthermore, while much online information appears widely and freely accessible, it is actually delivered in a way optimized for each individual. In other words, information is filtered to naturally gather "what one wants to see," often excluding "what one doesn't want to see."

Consequently, the more one trusts conspiracy theories (the more one selects and accesses such information), the more the information reaching them becomes purified and reinforced within that framework. This creates the illusion that "it's common sense" or "those in the know understand," leading people to become deeply, deeply convinced without even realizing it.

People who feel they've finally found the reason behind their lingering unease naturally spread that reason. They believe doing so will make society better. They feel they have many allies. Yet when they boldly voice their views, they encounter unexpected counterarguments and backlash, leading to a major divergence in paths. Some listen to opposing opinions and re-examine their own thoughts. Others, conversely, see this backlash as the very reason society cannot change, igniting a burning sense of mission to spread the truth at all costs.

The powerful motivator for the latter is the joy of having something meaningful to do. Having previously felt trapped in a dead-end situation where nothing seemed to work, and finding little meaning in daily routines, the belief that overcoming this will open a brighter future is incredibly compelling.

As a result, they act with increasing passion and become more stubborn, eventually losing control. Even though they realize it's strange, their drive to make things better wins out, and they can't turn back. Because if they let this go, they'll revert to that version of themselves again—one without any sense of progress, unable to find hope for the future.

Incidentally, so-called conspiracy theories aren't entirely fabricated. If anything, it's precisely because they contain a great deal of truth that people come to believe them. Minor inconsistencies are overlooked precisely because the larger picture holds so much truth.

【The Desire That Haunts Me】

→ The desire to "protect what matters"

※For DDD's analysis of the new "11 Desires," see here

In the second part, we'll explore two specific examples: "Losing Control in the Name of Justice" and "Losing Control in an Unwinnable Game." We'll also discuss where Japan is headed as it begins to "lose control," alongside DDD's survey findings indicating that over half of Japanese people feel they are on the verge of losing control.

[Survey Overview]

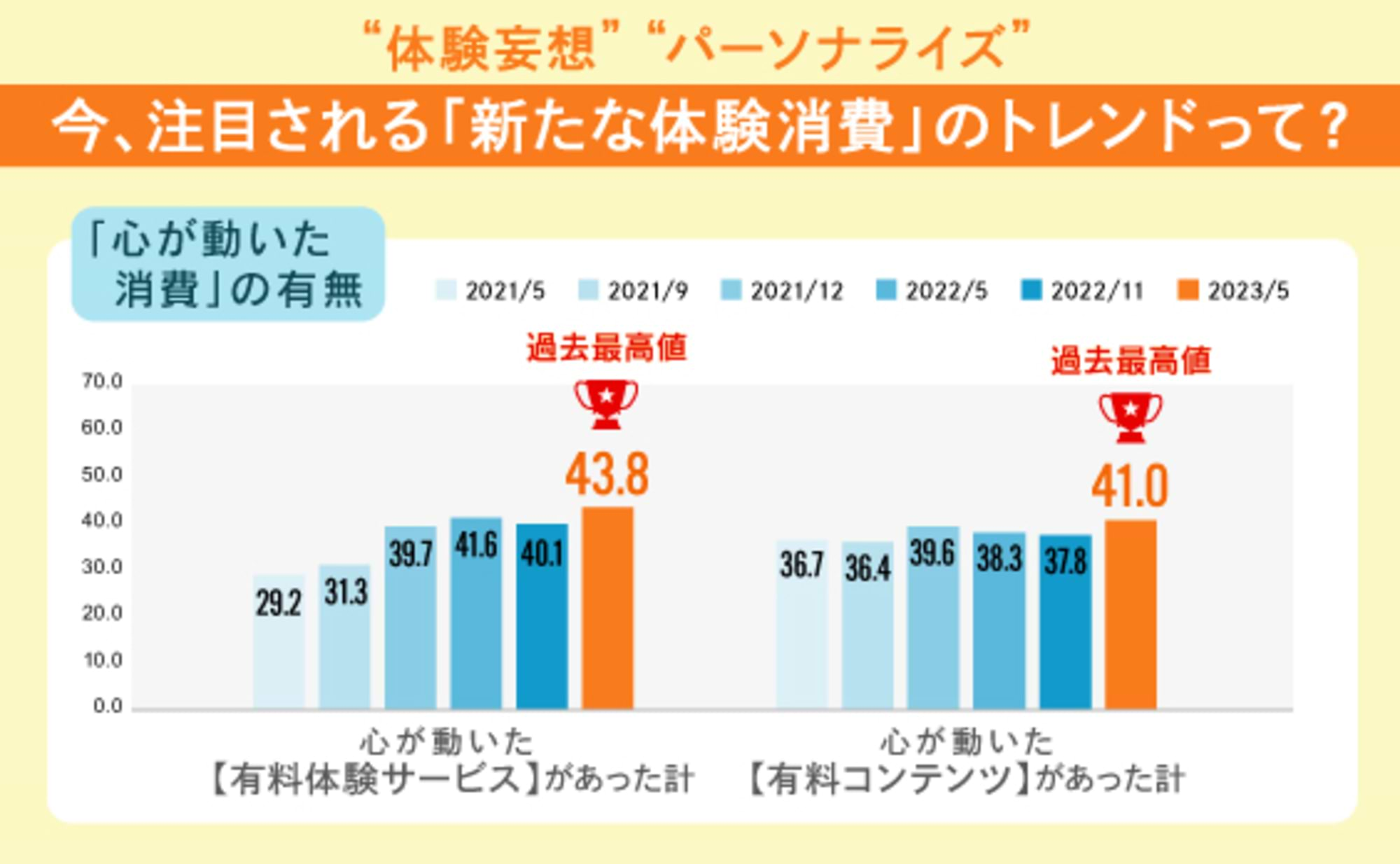

The 7th Emotion-Driven Consumption Survey

<7th "Heart-Moving Consumption Survey" Overview>

・Target Area: Nationwide

・Respondent Criteria: Men and women aged 15–74

・Sample Size: Total 3,000 samples (allocated according to population ratio across 7 age groups: 15-19, 20s-60s, 70-74, and 2 gender groups)

・Survey Method: Internet survey

・Survey Period: Wednesday, November 1, 2023 – Monday, November 6, 2023

・Survey Sponsor: Dentsu Inc. DENTSU DESIRE DESIGN

・Survey Agency: Dentsu Macromill Insight, Inc.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Hayato Yamagami

Dentsu Inc.

PR Solutions Division

Chief Communications Director

By mastering three fields—creative, promotion, and PR—we design communications that seamlessly integrate paid, earned, and shared media. Our scope spans from zero-yen sampling to ¥10 million luxury goods, brand consulting, and now SDGs initiatives. My hobby is solving problems—hence, I absolutely love helping people in need.