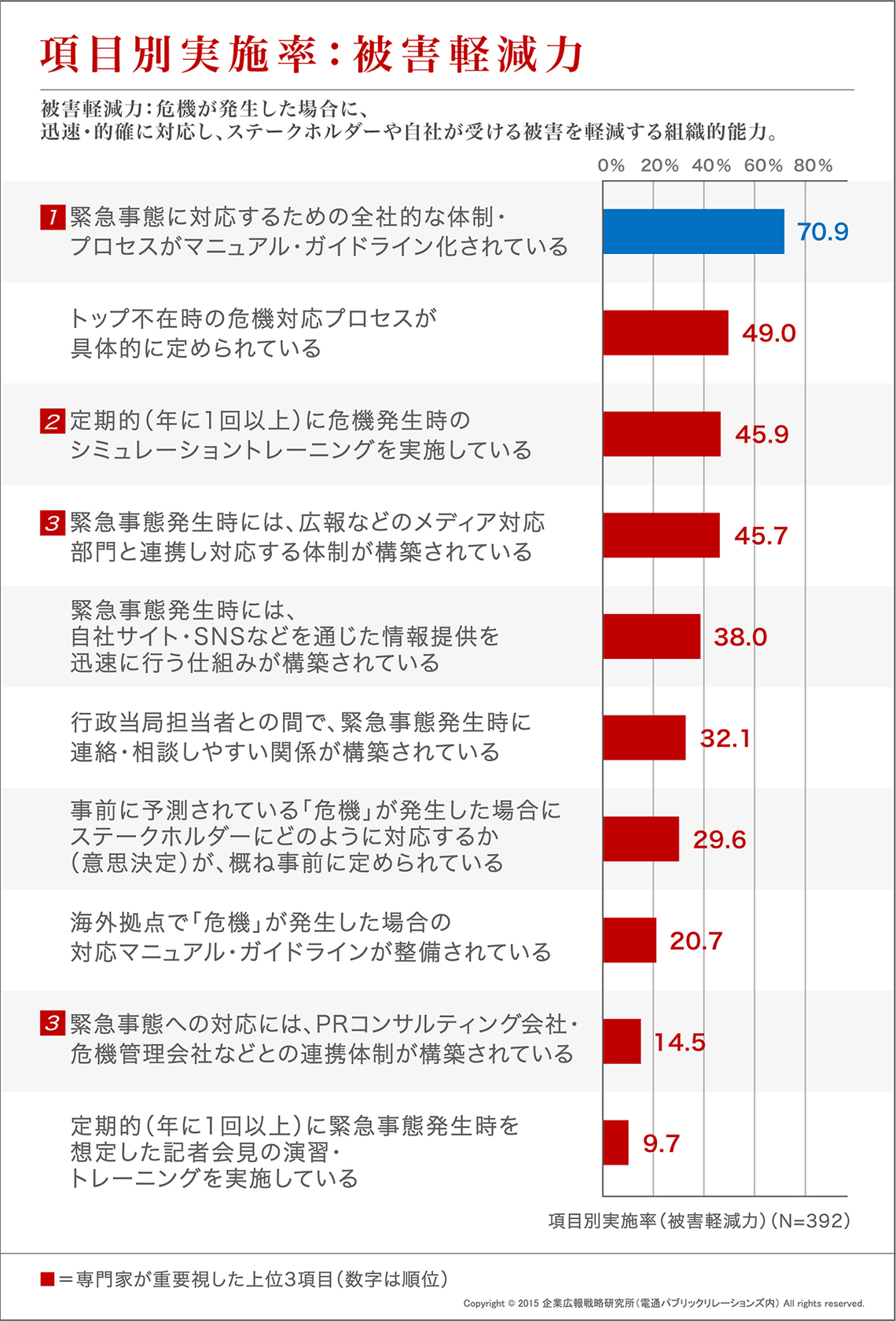

This installment focuses on "Damage Mitigation Capability," one of the five crisis management competencies covered in this series. Our institute defines it as "the organizational capability to respond swiftly and appropriately when a crisis occurs, thereby mitigating the damage suffered by stakeholders and the company itself. "

While "damage" can vary greatly depending on the nature and circumstances of the incident—ranging from financial to human—one crucial form of damage that must not be overlooked is "reputation."

Reputation means "(good) standing," encompassing "trust" and "credibility." Losing these can lead to actions like "We will never do business with them again" or "We won't buy that brand for a while," potentially putting a company's very existence at risk.

The ability to effectively manage the aftermath to prevent damage to this vital reputation is what defines "damage mitigation capability." I'd like to discuss this using two key concepts: "initial response" and "apology."

No matter what anyone says, the key word in scandal response is "initial response."

Criticism incurred due to flawed initial responses persists indefinitely. No matter how hard you try afterward, you'll be labeled as having reacted too late, delaying trust restoration.

For example, when a personal information leak is confirmed, investigating how it happened, where it originated, and what information was compromised takes time. If the company wallows in victimhood—blaming cyberattacks or maintenance contractors—it faces harsh criticism under headlines like "Delayed Response," questioning why the disclosure wasn't made sooner to prevent further damage.

In today's world, information spreads incredibly fast via the internet, demanding speed throughout the entire response process. It's no exaggeration to say speed is a sign of sincerity.

The "initial response" demands explosive speed – specifically, how quickly information is shared between organizational leaders and those directly involved to begin formulating countermeasures. This is precisely where an organization's core strength is tested.

In this crisis management capability survey, our institute included the question "Are company-wide systems and processes for responding to emergencies documented in manuals or guidelines?" as one measure of "damage mitigation capability." Experts also emphasize this point. It tests whether crisis response actions are clearly documented within the organization and whether they are useful manuals that can be retrieved and immediately utilized when needed.

The three monkeys—see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil—won't cut it.

"Reporting" is also crucial. Nothing can begin without a solid initial report reaching the response headquarters. Bringing bad news up the chain requires considerable courage, especially for company employees.

However, there are countless examples where failure to report initially led to whistleblowing and major scandals. It's also crucial to "listen with an open ear." There have been cases where information was blocked by supervisors who dismissed reports from subordinates as bothersome, ultimately leading to major accidents.

"Hopeful thinking" – wishing the problem isn't real – and "lack of imagination" – dismissing the possibility – are also reasons reports stop. We must re-emphasize the "report, communicate, consult" (ほうれんそう) principle taught to new employees across the entire organization. For sound judgment, it's vital that managers firmly catch even the unpleasant ball.

To protect the organization's reputation, a heartfelt "apology" is essential.

Now, for the second half: points to consider when disclosing information. Careful consideration is needed regarding how to explain the misconduct that has occurred to the public, but in most cases, an apology cannot be avoided.

That said, holding a press conference for every minor issue isn't the solution. According to the "2015 Crisis Management Survey," media professionals cited criteria for holding a press conference, including when "human casualties are involved," "there is potential for recurrence or escalation," or "illegal activity is suspected." In such cases, a press conference should be held to provide a proper explanation.

No one relishes bowing their head in public, especially when no laws were broken or the misconduct stems from subcontractors or partner companies. Yet, even then, media scrutiny inevitably focuses on the organization's "moral responsibility" and "management accountability." Therefore, once the decision to apologize is made, it must be done with sincerity and heartfelt remorse. A half-hearted apology risks worsening the situation.

The sight of multiple corporate executives bowing in perfect unison might be rare overseas. Yet, Japanese media strongly demands this bowing scene—the press conference—to capture that symbolic image of the scandal.

What must be carefully considered here is that simply bowing one's head is not enough. A perfunctory, half-hearted bow, done with the attitude of "Just apologize, right? I'll apologize," is instantly recognized by observers as lacking sincerity. Society will then dismiss the company as being of that caliber.

I once heard from a senior editor in the social affairs department of a national newspaper that the keyword "zanshin" (remaining presence of mind) is key; how one raises their head after bowing reveals whether the apology was heartfelt.

What constitutes a "proper apology"? What must be deeply engraved in one's mind during a press conference is this: the apology should be directed not at the journalists in front of you, with their piercing stares or provocative questions, but at the people beyond the journalists and camera lenses.

It's easy to forget this momentarily when the camera flashes go off, but we must constantly remind ourselves of this fundamental truth: the true recipients of the apology are not the media, but the stakeholders. We must consciously choose our words, our attire, and maintain a composed expression with them in mind.

That is why the "impression" you make in that moment is so important. Mr. Martin Newman, who coached Christel Takigawa on her presentation of "omotenashi" (hospitality) during the bid for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics, suggests from his experience that the "impression" you give to those around you is composed of three elements: "visual," "vocal," and "verbal." and "verbal" elements, and that about half of that impression is made up of "visual" elements such as posture, gestures, eye contact, and facial expressions.

I hope you now understand that the impression made by an organization's executives when apologizing is a very important factor in minimizing damage to its reputation when a scandal occurs.

As the saying goes, "the name reflects the person." Never forget that even a single apology is an expression of the company's stance, history, and culture. We will refrain from discussing here what impression a "dogeza" (kneeling apology) leaves on people.

First and foremost, it is essential to thoroughly eliminate careless remarks like "I haven't slept," as well as any "preconceived notions" or "victim mentality" that invite unnecessary criticism. By offering a sincere apology, the organization can project an image of being "a rather solid company (organization)" and "I hope they recover quickly." To achieve this, I reaffirm that sincere, swift initial response and a heartfelt apology are paramount.