This installment focuses on the "Creative Test (CR Test)." Conducted by Dentsu Inc. for employee training for over 30 years, this test has also contributed to discovering creators within the company. The "slightly unusual problems" unique to the CR Test have left a deep impression on many test-takers. While exploring the relationship between the CR Test and active learning, we examine the importance of "questions without definitive answers."

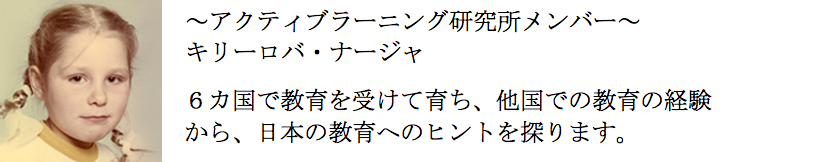

Professor Okuma, along with Dentsu Inc.'s Miyako Ito and Yu Kato, who have been involved with the CR Test for many years, discuss the CR Test and active learning. The session was facilitated by researcher Nadezhda Kirillova.

Creating tests without correct answers for 30 years

Nadezhda: I've taken the CR Test myself, but even within the company, few know how it was created or the behind-the-scenes stories, so I'm really looking forward to today.

Ito: As part of the HR side's administrative office, I've been involved in discovering and nurturing creative talent, and I've been involved with the CR Test for about 30 years. I don't create the CR Test questions alone; I consult with the Creative Directors in charge of development within the Creative Bureau, including Mr. Kato.

Kato: I have extensive experience in the creative field, including about 13 years as a copywriter. After that, I spent 20 years working in various departments focusing on nurturing and evaluating young talent. Now, I'm in the Development Department handling training programs.

Okuma: You two are remarkable. You've supported Dentsu Inc.'s creative personnel for nearly 30 years.

Naja: I've also benefited greatly from your guidance. Professor Okuma, could you please explain active learning again?

Okuma: Most school lessons are conducted in a "lecture format." In terms of efficiently imparting knowledge, it's an effective method.

Recently, it's been said that 49% of current jobs will disappear in 20 years. With the spread of computers, anyone can utilize big data, so I think this could very well become reality.

I believe school education must undergo significant change so that all children can thrive in such an era. It's not just about acquiring knowledge; they need to develop skills that allow them to apply what they learn in school in versatile ways. Furthermore, they must also acquire the "ability to create the future." That's why, alongside lecture-style classes, "active learning" – where children engage with each other to solve problems – has become increasingly important.

This represents a fundamental reform in teaching methods.

However, schools don't seem likely to change that easily. Just the other day, I met a teacher who said, "So, should we just set aside time for active learning once a week?" Another person asked, "What if academic performance drops because we do active learning?"

If the sole focus is on boosting current test scores, I can understand these teachers' perspectives. Yet, they fail to recognize that merely accumulating knowledge is insufficient for children to thrive in the world ahead.

Therefore, it's crucial to redefine what academic ability means for children and focus on equipping them with the power to proactively create new futures.

That's why I believe school lessons, like the CR Test, need to challenge both teachers and students with problems that don't have a single correct answer. However, modern schools lack the know-how to do this. Yet, Dentsu Inc. has had the CR Test for over 30 years – I thought this was remarkable.

I believe this CR Test, with its open-ended problems, could serve as a compass for implementing active learning in schools.

Children who hesitated to answer

Naja: I hear you tried creating CR Test-style problems yourself.

Okuma: I had the children try problems similar to the CR Test. Their reactions were the exact opposite of "interesting" or "want to do more."

Kato: What kind of problem was it?

Okuma: "We want to launch a major campaign to sell rubber bands. The size is up to you. What purpose will the rubber bands serve, and what size will you make them?"

Unfortunately, they couldn't think deeply about this problem. I wondered if they lacked the courage to tackle a problem without a clear right answer.

Worse still, some children asked, "Teacher, is there a right answer to this?" It seems they become anxious the moment they encounter a problem without an immediately obvious solution.

Perhaps they can't endure the "time of patience" required to face problems where the answer doesn't immediately come to mind or where they don't understand. I suspect the root cause is that today's children have developed the habit of expecting instant answers. The recent trend of individual tutoring and internet searches seems to be accelerating this. They've grown accustomed to a system where if they don't understand something, they just click or raise their hand and get the answer instantly.

Ito: Do they assume the teacher has the correct answer and just try to find it?

Ōkuma: Yes, that tendency seemed strong. I tried giving hints like, "What do you think would happen if you made the rubber band bigger?" but it didn't work.

Ito: Maybe it's not that the idea hasn't crossed their minds at all, but that they feel embarrassed to voice their free-thinking ideas. Perhaps it's okay if the time they spend questioning themselves is short. What if we just let them casually say whatever comes to mind, no matter how random?

Ōkuma: That's true. They might be too embarrassed to speak up for fear of being wrong.

Kato: I think teaching them brainstorming techniques would help. Creating a space where they know "no matter what they say, they won't get scolded, embarrassed, or laughed at" is essential.

Ito: Are there few such spaces in schools?

Ōkuma: Hmm, perhaps such situations are indeed scarce in schools. With active learning becoming a hot topic, we've started hearing the term "brainstorming" even in schools.Through my 10 years of joint research with Dentsu Inc., I feel I've somewhat mastered the "brainstorming" method. That's why, when I see brainstorming sessions in schools now, something feels off. One reason is that the teachers themselves haven't experienced the freedom to speak openly without criticism or the proper way to facilitate discussions. So, even when they call it brainstorming, it doesn't become a process of elevating each other's ideas; it just turns into the same kind of compromise-seeking discussion as before.

Approaching brainstorming is still quite advanced. In reality, many teachers still focus their efforts on guiding students toward the correct answer. When a student gives an answer, they prompt them with hints like, "Close, but not quite," "Getting there," or "Hmm, feels a bit off," aiming to get them to say the right answer.

Ito: There's no gray zone where answers could potentially be correct, right?

Okuma: Exactly. So students are constantly expending energy trying to figure out the "correct answer" the teacher has in mind.

Naja: Since CR tests are based on the premise that there is no single correct answer, knowing this versus not knowing it probably makes a big difference. Basically, most school tests have only one correct answer. Saying "Write down as many as you can" might lower the barrier.

Ōkuma: It takes time to understand a culture where "anything you write is correct."

Naja: Overseas, teachers often say things like, "I don't have that answer either," or "What do you think?" It's probably important to avoid creating an atmosphere where the teacher seems to hold the absolute answer.

Drawing out ideas, not knowledge

Naja: Could you tell us a bit more about the specific CR test?

Ito: When testing external candidates for Dentsu Inc., we want to identify students with interest and aptitude in this field. We've also conducted it to help people understand what Dentsu Inc. actually does. Internally, with over 130 new hires annually, one goal is to find those interested in creative thinking.

Creative thinking isn't just for creative department employees; it's necessary for sales and HR roles too.

The larger goal is to create problems that stimulate the idea-generating brain and encourage everyone to think more flexibly.

Okuma: What kind of problems do you create?

Kato: "Come up with an ad that makes people order udon at a soba restaurant" was a good one. Since everyone knows both soba and udon, there's no bias in prior knowledge.

If we get lots of creative answers like "Feed them soba every day for 365 days before bringing them here," that's a success.

Naja: Do things sometimes not go well?

Kato: Questions like "How can we get more people to visit Tokyo Tower?" ended up biased because people closer to Tokyo knew more about it. "Explain a computer to someone from the Edo period" also didn't work well because the answers followed the same pattern. Since participants couldn't look anything up during the test, good questions are those that draw out interesting ideas regardless of how much knowledge someone has.

Questions that worked well included things like "Create an advertisement recruiting young people to join a sumo stable." For example, we got answers like: "All-you-can-eat, room included, naps included," "A job where you get praised the fatter you get," "Slim folks, starting next tournament, we're switching to weight divisions," and "Your marriage partner will almost certainly be beautiful." I think a good problem is one that sparks ideas from various angles.

Ōkuma: Those answers are fascinating. Hearing them makes you think, "If I were asked that, I'd come up with this answer," and the next solution just pops into your head. It's not just the problem itself; other people's answers are incredibly stimulating.

Ito: Other people's answers spark new ideas from different people. That's exactly what brainstorming is.

Ōkuma: Stimulating each other like this, letting thoughts flow freely, and deepening understanding together. This is a crucial aspect in the classroom and something we should reference in active learning too.