This New Year's Day, two types of ozoni soup lined up at our house again: Tokyo-style clear broth with square rice cakes, and Takamatsu-style white miso with sweet bean paste rice cakes. Two bowls, never sharing. Everything was peaceful, just like always.

Come to think of it, I believe it was New Year's Day in 2003. A message was left on our home answering machine. The caller was Masatoshi Koshiba, who had received the Nobel Prize in Physics the previous year. He had seen the New Year's card my mother had sent him for the first time in 40 years to congratulate him, and he had contacted us.

My mother, who is now 85 years old, studied piano at the Eastman School of Music at the University of Rochester in New York after the war. Naturally, she was a poor student struggling financially, but it was the "good old days" of the 1950s in America. She was blessed with many happy memories.

Around the same time, Mr. Koshiba was studying for his doctorate at the University of Rochester. He said that the few Japanese students studying abroad at that time would sometimes get together and hang out.

When my mother heard the news about the Nobel Prize, she said, "Mr. Koshiba is an old acquaintance of mine. He has a great sense of humor..." I dismissed it as a tall tale, but it turned out to be true. After that, I met Mr. Koshiba once when I accompanied my mother, and I was struck by how interesting human connections can be.

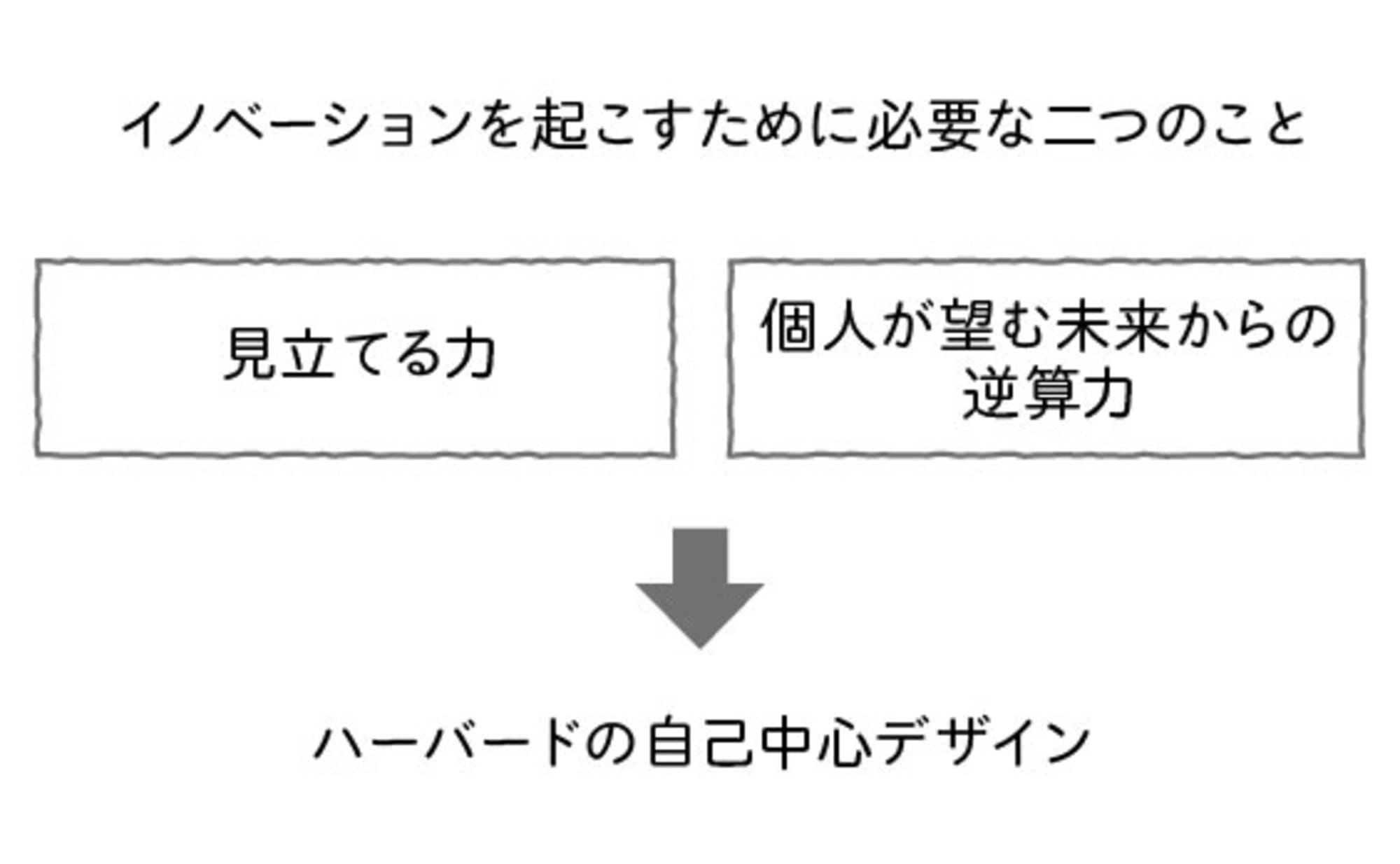

Now, without needing a New Year's resolution, my personal goal is "to spark innovation through advertising methodology." I aim to prove that the advertising industry's methods for managing ideas and its creativity itself hold significant value in other fields.

To achieve this, I immerse myself in corporate environments, understand their organizational thought processes, and through repeated dialogue and practice, spend years embedding a "methodology for idea creation." While my own persistence is essential, it's even more crucial that executives commit to believing in this methodology. The time before results appear is never short. Changing methodology inevitably creates friction within an organization.

Without meeting individuals willing to overcome such stress, the project itself wouldn't exist. That means I couldn't get closer to my goal. Every project currently underway started with a small connection that expanded.

I'm turning 50 this year. How many more large-scale projects, requiring years of commitment, can I take on in the time I have left? Thinking about that makes me want to cherish every single job and connection, and seize as many opportunities as possible.

Now then, a little aside.

Innovation is about finding "new perspectives," and for that, a flexible mind free from preconceptions and a sense of humor are essential. Professor Koshiba, who pioneered the field of "neutrino astronomy," has a very amusing anecdote.

Professor Koshiba, serving as a substitute teacher at a junior high school, posed this question to his students: "What would happen if there were no friction in the world?" The answer? "Without friction, the pencil tip would slip, making it impossible to write on the exam paper." Therefore, "a blank answer sheet is the correct answer."

What a wonderfully free-thinking idea!

Please, help yourself!