Dentsu Inc. is focusing on developing solutions and disseminating insights to leverage creativity for business challenges by extending the capabilities and experience of creators cultivated over many years in the advertising field into the business domain.

How should creativity be applied to management challenges?

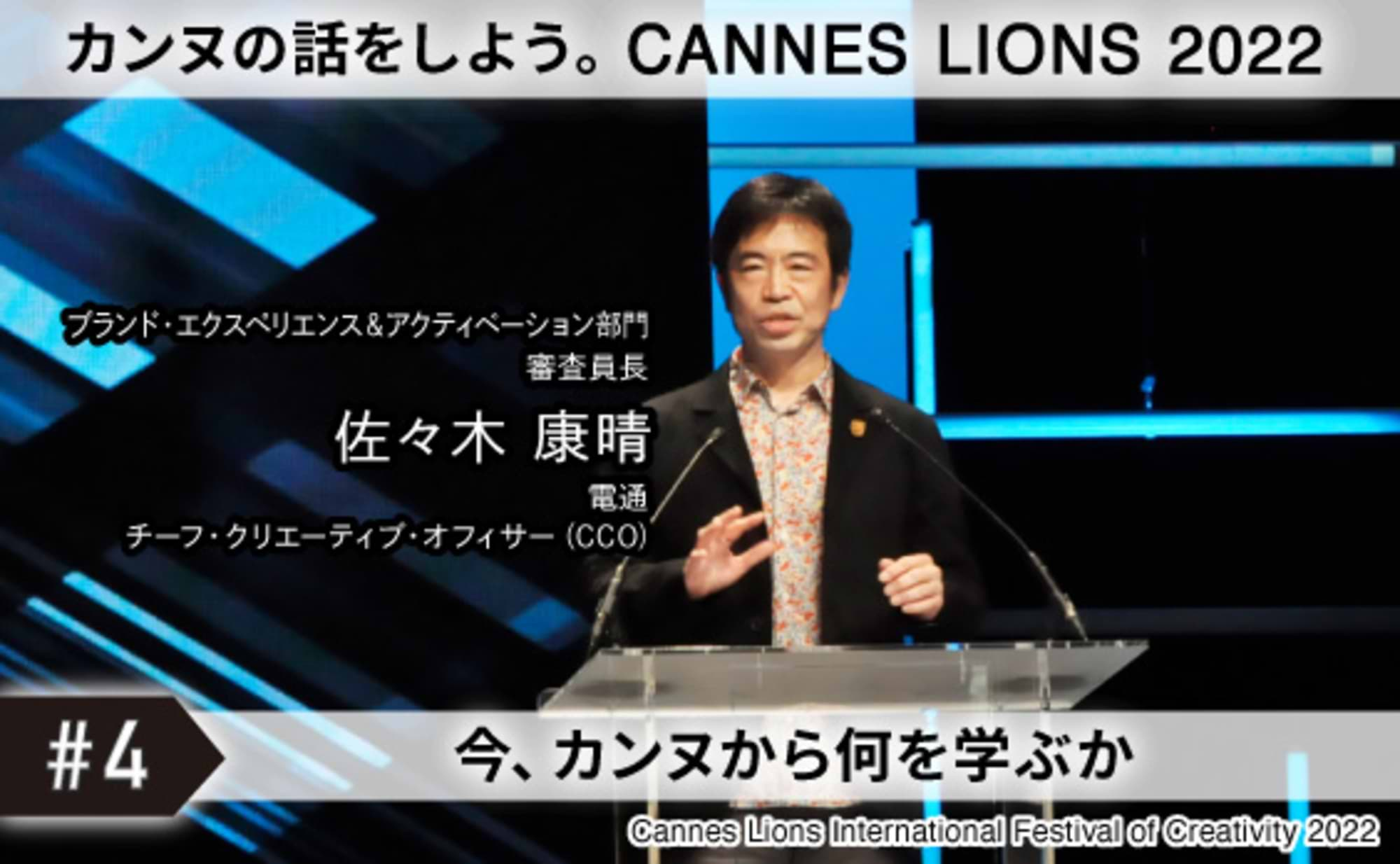

To unravel this question, Professor Emeritus Ikujiro Nonaka of Hitotsubashi University, a management scholar, and Yasuharu Sasaki, Chief Creative Officer (CCO) of Dentsu Inc., held a discussion on the theme "Creative Thinking Essential for Future Management and the Potential of Creativity."

The "SECI Model" Born from Japanese-Style Innovation

Sasaki: Recently, with the spread of digital technology and shifts in consumer awareness, the way companies connect with people is rapidly changing. Our work as creators has also expanded beyond traditional advertising communication. It now encompasses diverse areas like experience design, product/service development, organizational building, community building, and even formulating management strategies. We are increasingly expected to serve as partners who jointly foster corporate growth and innovation.

To achieve this, we build teams with diverse expertise, articulate the vague concerns of management to generate new concepts and ideas, and then actually shape and execute them.

I felt that the SECI model—a knowledge management framework focusing on intellectual creative activities, as proposed by Professor Nonaka—closely resembles the activities we creators practice daily. What was the background behind the creation of this SECI model?

Nakano: After working in industry for nine years, I enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley's Haas School of Business. While specializing in management research there, I had to choose a second discipline from the social sciences. I selected sociology by process of elimination. However, Berkeley's sociology department at the time boasted some of the nation's top professors, and I was thoroughly drilled in how to develop concepts and theories.

After returning to Japan, I researched development cases at Japanese companies like Fuji Xerox and Honda with people I met at Berkeley's graduate school, including Hirotaka Takeuchi (a management scholar). The "SECI Model" was developed based on these research findings.

【SECI Model】

A spiral process for converting individual tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge and continuously creating knowledge throughout the organization.

(1) Socialization: Perceiving reality or gaining tacit knowledge by adopting others' perspectives.

(2) Externalization: Grasping the essence through dialogue and transforming it into explicit knowledge using analogies and hypotheses.

(3) Combination: Freely combining all knowledge to generate systematic collective knowledge.

(4) "Internalization": Putting theories and narratives into practice, embodying organizational knowledge, and driving self-transformation.

By spiraling these four phases, we aim to elevate the entire organization.

New value emerges precisely when subjective perspectives collide.

Sasaki: Among the phases of the SECI model, which process is particularly crucial?

Nonaka: It all begins with the initial "Socialization," meaning empathy. While "sympathy" is a similar term, sympathy involves objectively perceiving and judging what others feel, whereas empathy means synchronizing with others unconsciously. The most crucial aspect of this empathy is that it occurs in pairs, not alone. It's the interaction between distinct entities—"me and you"—clashing our subjective perspectives without compromise. This is what philosopher Husserl called "intersubjectivity," and it's through this that we can create new meaning and value.

Sasaki: I see. While many companies practice development methods like the SECI model, I suspect that cases where it doesn't always work well might stem from issues in the process of co-creation.

Nakano: The problem with corporate management these days is that it's fallen into a kind of "analysis paralysis syndrome." The mindset that starts with objective analysis first has become entrenched. They take concepts from other companies and try to fit them to their own reality. In short, they're not good at creating meaning proactively. But if you don't create new meaning, it's not a concept.

The SECI model begins with "sympathy," which isn't about exchanging objective opinions. As mentioned earlier, "mutual subjectivity" is crucial.

Sasaki: Sometimes we push forward with projects by openly clashing our subjective views without holding back. Other times, we take a facilitator role, listening to everyone's opinions and steering things toward a consensus that avoids complaints. While the latter approach certainly makes consensus easier, the former often yields more exciting, powerful concepts.

Nonaka: In this context, "subjective" essentially means sensibility, and the quality of experience is crucial. If experience is lacking in quality or quantity, clashing subjective views will only yield poor language. And then, engaging in serious, thorough debate. Creating that extreme state where you feel cornered, thinking, "I am the one generating ideas!" I think this is close to the environment creative teams find themselves in. What do you think?

Sasaki: Exactly. Dentsu Inc.'s creative teams are filled with members possessing diverse expertise, curiosity, and strong, deep experience. When we generate ideas, everyone embraces a sense of ownership, fully empathizing with the client or user's perspective. We push ourselves to the absolute limit, to the point where we believe no one else could possibly come up with it. Creators might not consciously realize it, but they're already adding value from the very stage of co-creation before ideas are even proposed.

Each person wields their refined sensibilities as weapons, subjectively clashing opinions. You've shared what could be called the fundamental essence at the root of innovation. Next time, we'll delve deeper into the key points of this collaborative process.