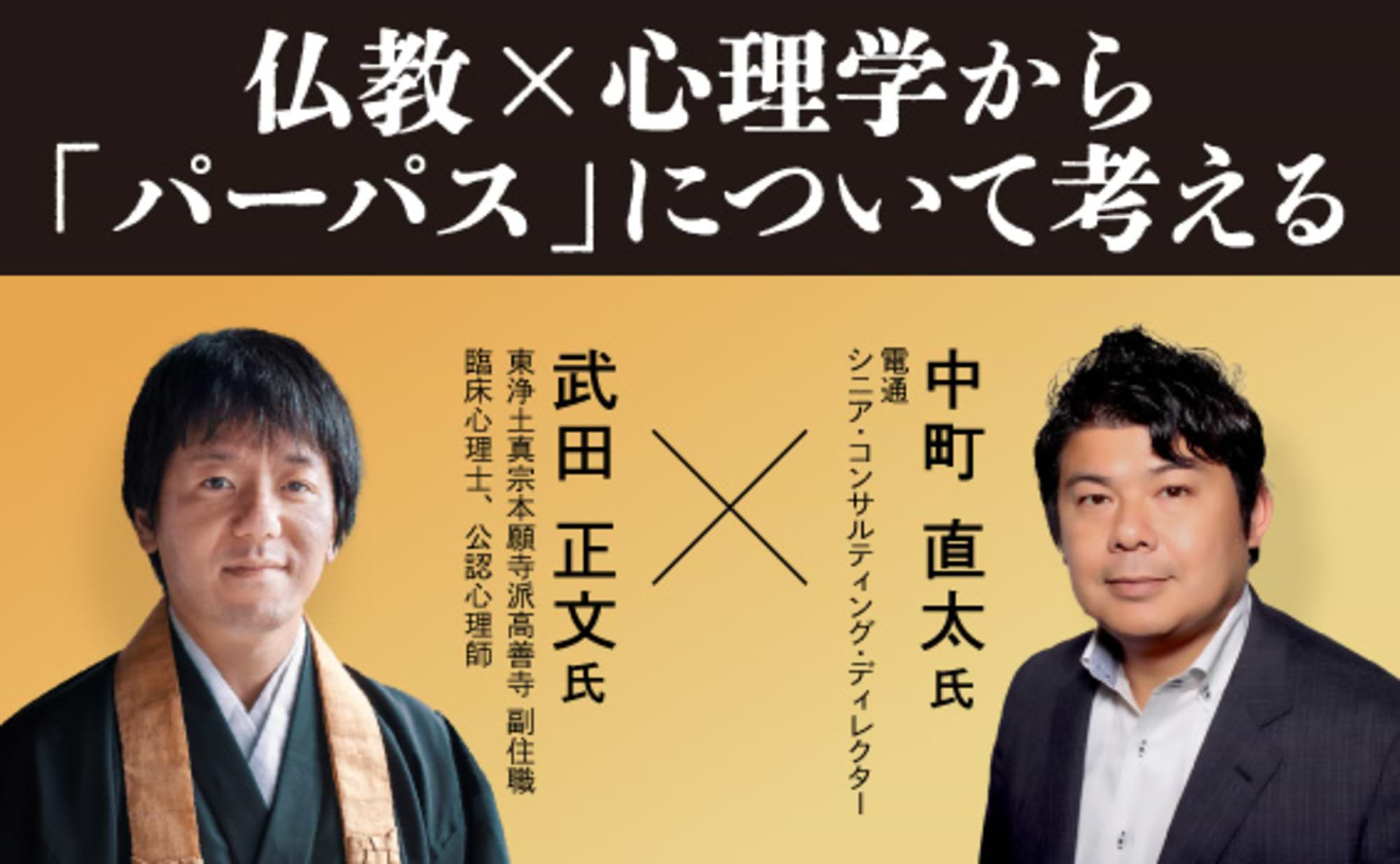

In today's world of diverse values, companies increasingly emphasize clearly articulating their purpose within society. As highlighted in this series, "learning from humanities knowledge" is gaining attention—with companies incorporating "philosophical dialogue" into shaping corporate philosophies and training.

This time, we focus on "SF Prototyping." This method involves envisioning fantastical, out-of-this-world futures to conceive values and businesses that don't yet exist, then working backwards to determine what actions are necessary in the present.

Naota Nakamachi of Dentsu Inc. Corporate Transformation Department interviewed Yuki Namba, an aesthetician, critic, and SF researcher who offers "SF Prototyping" workshops to companies through both newQ projects and personal projects. They discussed the characteristics of "SF Prototyping" and its effectiveness in business.

Creating tangible, emotionally resonant prototypes that feel like they've come from the future

Nakamachi: "SF Prototyping" is a business method gaining traction even within large corporations. That said, many likely wonder how science fiction can actually benefit business. Could you first explain what kind of technique "SF Prototyping" is?

Namba: I see "SF Prototyping" as a practical method for creating prototypes that feel tangible and emotionally resonant, as if they've arrived from a near or distant future that might one day come to pass. The goal is to discover and express what might happen as a result of creating a new service or product.

Crucially, these prototypes should have a "tangible feel" – something that touches the heart. A major goal of SF Prototyping is to trigger unprecedented emotional reasoning: what value do our envisioned new services or products hold? Conversely, what might make them slightly unappealing?

Why SF? Because we want to imagine a slightly accelerated future. We want to explore the future through fiction and expand our thinking: "If we do this, might the future become more appealing?" We envision the future in fictional form, then backcast to determine how close we want reality to come. Then, we consider what we can achieve now. That's the fundamental concept of "SF Prototyping."

Nakamachi: Hearing you speak, I felt "tactility" is the key word. Companies often think, "Let's envision the future decades from now," and "What vision could we hold within that, and what businesses or services could we create?" To feel that tactility, they use the form of SF to depict the future. Is that how we should understand this approach?

Namba: Yes, that's right. Beyond tangibility, I also think "uneasiness" is crucial. For example, if we consider, "If men could become pregnant and give birth to children in the future, 'father-child health handbooks' might become commonplace," many men might feel their existing values being relativized, stirring their emotions. That flustered feeling happens at the moment when values you took for granted start to be reconstructed. I feel the real interest lies in that flustered moment—that sense of "A completely different value system is coming in now."

Nakamachi: Indeed, envisioning an unforeseen future makes you feel flustered. I think innovation happens precisely when the fixed notions you've cultivated are overturned.

Namba: Simultaneously, I sense a motivation to resist a world built solely on technology-first principles—a desire to outpace technology's speed. Technology is like a creature evolving voraciously. It's crucial for humans, with conscious intent, to properly tame this monster. That's why I believe "SF prototyping" and philosophical reflection are necessary.

Nakamachi: Rather than predicting, "In decades, this technology will surely exist, and the world will be like this," we must consider what a truly valuable future actually is. That's the most crucial point.

Namba: Exactly. I believe it's vital to explore the future not as "technology-driven," but as "human-driven" and "life-driven."

Considering future users who don't yet exist

Nakamachi: What kinds of consultations do companies interested in SF prototyping bring to you, Namba-san?

Namba: One common pattern is "Near Future × Ethics." A major corporation had advanced elemental technology development to the point where implementation seemed imminent. However, with technology leading the way, concerns arose: "Will this technology truly make people happy?" "Are we overlooking potential unhappiness?" Motivated by the desire to validate this through tangible fiction, they requested "SF Prototyping." The resulting sci-fi novel served as a communication tool for extensive internal and external discussions.

The other pattern is "distant future × value." To capture a more distant future and explore the question "What will future business look like?", we conducted "SF prototyping."

These two are representative examples, but within the gradient of "Near Future × Ethics" and "Distant Future × Value," they can be combined in any way.

Nakamachi: Compared to other consulting approaches, where does the uniqueness of "SF Prototyping" lie? While there are various approaches to creating new businesses, could you explain the characteristics of "SF Prototyping"?

Namba: One key difference is its distinction from design thinking. Design thinking focuses on existing users and considers how to solve current problems. In contrast, "SF Prototyping" is "post-human-centered." This term was introduced in the recent book "How to Break the Worn-Out Future? Creating and Using 'Stories' to Rewrite the World" (Kobunsha) by Michito Miyamoto, a fellow researcher of mine (science culture writer and applied literary scholar). It means centering on humans who do not yet exist.

If developing products or services for 10 or 20 years from now, the world's situation and social systems will likely differ from today. This approach involves identifying what would most delight users who don't yet exist, spotting signs of this, imagining the feel through prototyping, and discovering value.

For example, if supporting immigrants currently living in Japan, it's effective to think design-thinking-centric: "What challenges do they face?" "What kind of support is needed?" On the other hand, if planning for "a Japan where immigrants surge in the future—what kind of urban or educational systems could be designed?"—that is, planning for people who don't yet exist—then "SF Prototyping" comes into view. That difference is significant.

Nakamachi: The idea of targeting people who don't yet exist is fascinating. However, in business, increasing the probability of success is essential. Since investments are made, they must yield significant results. This naturally leads many to question, "Can predicting the future through SF really be accurate?"

Namba: You're absolutely right. However, what "SF Prototyping" seeks isn't predicting the future. The crucial point isn't predicting the future, but stirring emotions, creating excitement, and discovering new value. As the title of a book by consultant Kyosuke Higuchi, who practices SF Prototyping, states: "The Future Is Not to Be Predicted, But Created" (Chikuma Shobo). In other words, we use fiction to explore value. While it's difficult to clearly quantify how much it helps business development, I believe it expands ideas, creativity, and imagination.

Nakamachi: I see. "It's not about predicting the future" is a major point. It's not about science fiction writers deriving a "correct answer" like "this is how the future will be." Instead, it uses the power of science fiction narratives to explore what kind of value, not yet existing, could potentially emerge. That process is "SF Prototyping."

Namba: Exactly. And after exploring value through "SF Prototyping," we then backcast to build a bridge between the future and the present. This can serve as a grand vision for future business development or provide hints for what we can do now. At that stage, we might also employ design thinking or scenario planning. The strength of combining these various workshops became even more apparent during a project we previously conducted with Loftwork.

Actually, I think this is something everyone does naturally. For example, when encountering a new idea, novel, or movie, it's natural to think, "This connects to current problems. Could we create a service like this?" "SF Prototyping" is about consciously applying this kind of thinking to make it even more interesting. When you think about it that way, it's simple, and you'll probably realize, "Oh, I've been doing this myself."

A space to freely discuss the future, transcending departmental boundaries

Nakamachi: I understand the significance and uniqueness of "SF Prototyping." Now, let's talk about the specific process. Where do you typically start with "SF Prototyping"?

Namba: First, forming a team and clarifying the purpose is crucial. While we often invite designers like product designers or design managers to SF Prototyping, I feel it becomes even more effective when we can build a team that includes people from technical development and sales. Since everyone is aware of real-world challenges in their respective roles, inviting diverse people prevents opinions from simply converging into one, leading to more interesting outcomes.

Regarding the purpose, we'll discuss and set it together—whether you want to consider the ethical challenges of existing technology or explore future value. Defining the purpose upfront prevents the question, "SF Prototyping was fun, but what's it actually used for?"

Nakamachi: How do you typically structure the workshop?

Namba: It varies greatly, but at newQ, we often start with a workshop to formulate the question. Then we hold a workshop to explore "what if" scenarios, followed by a workshop to review the works created by participants. This three-part structure is common.

For example, let's say we're doing "SF Prototyping" to explore the future of food. In the question-setting workshop, we start by considering things like: "Is eating alone better, or is eating together better?" or "Does cooking have to be done at home?" Focusing on questions related to value really expands the discussion. For instance, in Japan, there's still pressure on women, especially mothers, to cook for the entire family. We explore how to confront such institutional pressures.

From there, we move into the "what if" phase, expanding ideas further: "What if kitchens disappeared?" "What if even a 0-year-old child could cook?" Further, various futures of food emerge: "What if, like in the old days, everyone started cooking together in a shared kitchen? Would that be interesting?" From these, we select a few ideas that particularly resonate—"This connects to our business or vision" or "This feels tangible and touches the heart"—and ask participants to turn them into stories, like short fiction. Simultaneously, science fiction writers create works, presenting the diverse, fragmented visions of the future each person imagined.

In workshops focused on posing questions, we end up asking, "What value did this even have in the first place?" This allows us to find questions within values we previously took for granted or worldviews we had doubts about. Then, existing concepts and values bend, letting different meanings and contexts slip in. That's incredibly interesting. Once we've made everyone feel a bit uneasy like that, we start thinking about "what ifs."

Of course, we don't tolerate discriminatory or gender-inequitable remarks, but we encourage people to freely voice even the most eccentric ideas that deviate from current norms. When these ideas solidify into works, the conversation expands further. This continuous shaking up of values is the joy of "SF Prototyping."

Nakamachi: That sounds fascinating. But I imagine most workshop participants have never written a novel before. Won't they react with, "Huh? I have to write?"

Namba: Of course they will. That's why I tell them, "You don't have to be fixated on creating a story." It doesn't have to be a novel. It could be a future appliance manual, a pamphlet, or even a letter from a future city hall. A headline from a future newspaper works too, or you could think about what someone in the future might tweet.

Even if they write SF fiction, it doesn't need a climax or punchline, and there's no length requirement. The goal isn't to write a great novel, but to create tangible fiction that stimulates emotions and values. When I tell them they can create anything to achieve that, they think, "Well, I can probably do that." In fact, even if they're unsure at first, once they start writing, everyone enjoys progressing together. Ideas like "I never even considered this possibility" keep popping up, making it really fun.

Nakamachi: So there's variety in the output too. That really lowers the barrier to entry. Now, could you explain the process of backcasting from the created SF works to reality?

Namba: The crucial part is the reflection afterward. Depending on the initial goal, we sometimes accompany them all the way through design thinking workshops or creating service proposals as the output.

Nakamachi: So, you explore value through "SF prototyping," then return to reality to perform the necessary work to translate it into actual business or services. It essentially brings you back to a conventional project. But when everyone first explores future value together before tackling it, the sense of excitement and motivation is completely different, right? I think it's a powerful tool for breakthroughs, and it seems to play a role in removing everyone's mental biases and freeing them from constraints.

Namba: The larger a company grows, the less opportunity designers and researchers often have to communicate. Within that context, we build teams and discuss SF—something inherently strange for everyone. Fundamentally, the future is unknown to all. So conversations flow freely without fear of mistakes. This generates outputs infused with diverse perspectives—sometimes cool, sometimes humorous. I feel initiating "SF Prototyping" when starting future exploration projects is crucial.

Nakamachi: As a secondary effect of "SF Prototyping," it also seems likely to promote internal communication.

Namba: That's right. It's also a primary effect. When creating new ventures, you need the reassurance that "it's okay to freely talk about the future." Ensuring the psychological safety to discuss the future is, I believe, one of the essential values of "SF Prototyping."

Through "SF Prototyping," the bridge between purpose and business becomes visible

Nakamachi: I believe conducting "SF Prototyping" also clarifies a company's purpose. There's a growing movement now to redefine a company's raison d'être, its purpose. However, since purpose is meant to be a universal corporate philosophy, it inevitably becomes highly abstract.

While beautiful as a slogan, challenges remain in how to instill it among employees and how to create new value or businesses based on that purpose. This is where "SF Prototyping" comes in. By starting with highly abstract questions and collectively engaging in "SF Prototyping" to explore what value we can create for the future, I believe we can see a way forward that feels authentic to us. What do you think?

Namba: Personally, I interpret purpose as akin to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The Declaration outlines universal principles for humanity, right? However, it doesn't explicitly state what should be changed next or what actions should be taken. Article 6 states, "Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law." But what kind of system makes "recognition as a person" possible? That's left to our interpretation and implementation.

The interpretation of such ideals or purposes, like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, evolves over time. A purpose is also a kind of work of art; it exists to prompt us to ask, "What should we do?"

Nakamachi: How we interpret purpose and what actions we take. I found "SF Prototyping" to be an effective tool for unlocking constraints and simulating the future of a company. I would highly recommend "SF Prototyping" as the next step for companies that have created their purpose.

Namba: Furthermore, through "SF Prototyping," I believe we can update the purpose or consider the seeds of a new purpose. Prototyping-like thinking is useful both after and before defining the purpose.

Nakamachi: Purpose is something companies create by reflecting on the DNA cultivated since their founding and looking toward the future. With "SF Prototyping," you don't necessarily just leap into the future; you can also return to the past or your origins to explore value, right? It seems like we can gain insights into the way of thinking and the thought process involved in creating something new. Thank you for today.