Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

Are Japanese mothers happy right now?

Asako Osaki

Ikumi Toga

Dentsu Inc.

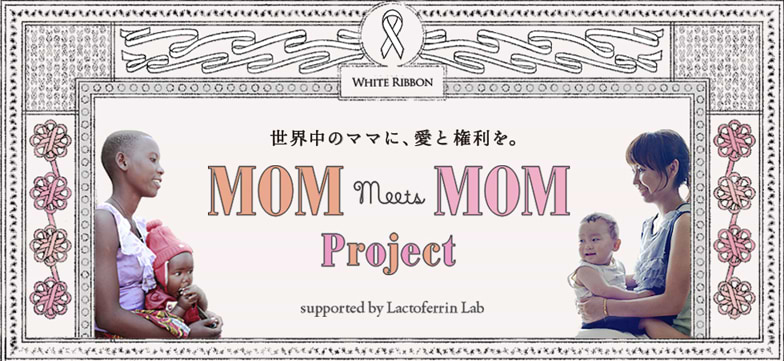

Globally, a staggering 800 women lose their lives every single day due to pregnancy or childbirth. To improve this situation, JOICFP, an international cooperation NGO supporting women in developing countries , and Dentsu GAL LABO, which handles communication for women, have jointly launched the "MOM meets MOM Project" as part of the White Ribbon Campaign to protect mothers and newborns worldwide. Saraya's skincare brand, Lactoferrin Lab, provides full support as a sponsor.

By raising awareness among Japanese mothers about the realities faced by mothers and mothers-to-be globally, we aim to foster mutual empathy and expand the circle of support. In this series, project member and author Ikumi Togasaki reflects on the state of maternal and child health in Tanzania, which she visited for an inspection in June. She explores the challenges and future possibilities for mothers in Japan and around the world.

In previous articles, we conducted undercover interviews with mothers raising children in Japan, the US, and France, revealing a somewhat surprising fact: Japan actually has some institutionally advantageous aspects. So, what is making life difficult for Japanese mothers today? What is needed for mothers to feel greater happiness? To explore mothers' happiness from a broader perspective, this time we talk with Asako Osaki, an international cooperation and gender expert involved in women's empowerment around the world.

◆Countries where pregnancy and childbirth become risks

Osaki: After witnessing the reality of maternal and child health in Tanzania through the MOM meets MOM project in June, and then hearing the candid voices of mothers raising children in Japan, the US, and France through undercover interviews, I've been thinking a lot lately about the global situation of mothers.

I want to think concretely about "What can we do to increase the happiness of mothers worldwide?" and "What can we actually do?" That's why I'd like to hear from you, Ms. Osaki, as an expert.

Ōsaki: Nice to meet you.

Tozaki: As a member of Dentsu Inc. Gal Lab and someone working in the communications field, I create projects centered on "empowering young girls." Your expertise, Ms. Osaki, is precisely "empowering women worldwide." Could you share the background that led you to this kind of work?

Osaki: The biggest catalyst was becoming a mom myself. It awakened a long-term vision in me: "What kind of society, what kind of world would be best for this child when they grow up?"

Tozaki: When did you become a mother?

Osaki: I was 24. Right after graduating university, I went to graduate school in New York. Just before classes started, I found out I was pregnant ... I went to the admissions office to say, "I'm withdrawing because I'm pregnant." They asked, "Why?" When I explained , "I'm about to give birth, and once I'm a mom, I'll have childcare responsibilities—I won't be able to continue my studies," the admissions officer confronted me: "There are plenty of people doing this—why can't you?" That's why I decided to continue graduate school.

Tozaki: Just now, it hit me—that feeling of thinking "I'm pregnant, I want to quit grad school, I can't keep going" is exactly the same situation as in Tanzania today. In developing countries like Tanzania, pregnancy is often the biggest reason female students drop out. Sometimes they get pregnant too young, but even in Japan, where the average age of first childbirth is rising, there's this image that pregnancy carries some kind of risk. Like the fear that if you get pregnant during a period when you're really working hard, you'll be sidelined.

Ōsaki: In Tanzania and Japan, there's this image that pregnancy and childbirth narrow women's choices, right? I think that perception was probably ingrained in me too.

Tozaki: What did you major in for graduate school?

Osaki: I intended to major in International Media, but the program involved a lot of fieldwork. I knew it would be impossible to manage that while pregnant and giving birth. So, I switched to specializing in International Human Rights and Humanitarian Issues. However, many students there already had field experience working in refugee camps or conflict zones. With no experience myself, I couldn't keep up at all. I thought, "This might be impossible..." and just tried to get through the semester while keeping a low profile . After taking a leave of absence to give birth, my worldview suddenly changed.

Witnessing a human being born and growing day by day brought the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other concepts I'd learned in class vividly to life. That's when I finally felt a genuine desire to study seriously.

Otsuki: I see.

Ōsaki: After returning from a six-month leave following childbirth, I had completely transformed into a dedicated student. Later, while interning at the Secretariat to help draft the UN's "Report on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Children," I worked on issues involving child soldiers and sexual violence—extremely brutal human rights violations. Overlapping these with my then two-year-old son made it unbearably painful.

That's why I moved into the field of " development assistance " – preventing problems before they occur, like reducing poverty, which is a root cause of human rights violations and conflict.

Tozaki: How did you transition from there to women's issues?

Osaki: After graduating from graduate school, I joined the UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), a UN agency headquartered in New York. About a year later, there happened to be an opening in the women's division, and I was assigned there.

Then, in 2001, while I was pregnant with my second child, a daughter, the terrorist attacks happened in New York. I happened to be off work due to morning sickness when I saw the footage, and I was truly shocked.

I gave birth the following April, but then I had to undergo surgery postpartum. The pain was excruciating, I developed a fever, and as my consciousness faded, I thought, 'If I were still in Afghanistan right now, I might have lost my life.'

Right after the attacks, the U.S. military began striking Afghanistan, and I couldn't shake the thought of the terrible suffering women and children were enduring there. I survived only because I happened to be in New York, receiving the latest medical care with the most advanced equipment . But I thought about mothers giving birth in Afghanistan at that very moment.

Tozaki: That's terrifying to think about. Your fate can change just based on where you are.

Ōsaki: As I raised my daughter, my focus shifted especially toward empowering young girls. Including my own experience, I feel like my focus gradually crystallized.

Tozaki: It sounds like you were guided by something.

◆Parenting isn't a handicap. It's a career!

Tozaki: In your work, have you ever felt that childbirth or childcare was a disadvantage?

Ōsaki: In graduate school, the attitude was, "Whether you get pregnant or give birth, if you're motivated, you can do it." UNDP was exactly the same. Having small children was absolutely no handicap.

However, while I was in university, I took the selection exam for a Japanese government program sending young talent to international organizations. Among Japanese female students, there was a rumor going around : " They apparently ask the women what they plan to do about marriage."

Osaki: What do they mean by "what about marriage"? Do you mean whether you will or won't?

Ōsaki: Exactly. Questions like, " How will you manage marriage while working at an international organization? " or "If you're assigned to a developing country, won't your parents object? " Men weren't asked those things. Plus, I heard there was no precedent of someone with children ever passing the selection.

Tozaki: That's a super hostile environment. How did you handle it?

Ōsaki: I actually approached it honestly, or rather , straightforwardly . Precisely because I've experienced pregnancy, childbirth, and raising a young child, I emphasized, "I can put myself in your shoes and provide support!" If I made excuses, it would play right into their hands. So before they could adopt a negative tone, I'd just say something like, "Actually, that's exactly my situation!" (laughs).

Tozaki: That's incredibly positive (laughs).

Osaki: If someone asked, "Ms. Osaki, I hear you have a child," I'd be like, "Oh, that's right ! Having a kid means I'm super skilled at time management! " (laughs).

Tozaki: That's an amazing comeback (laughs).

Ōsaki: To prevent them from perceiving it negatively, I'd say, "Thank you for asking! I'm glad you asked before I could give a negative answer!" Unlike other applicants, I'd say, "This is actually my advantage!" And apparently, I was the first woman with children to get hired.

Tozaki: You were the first! That's amazing.

Ōsaki: There really are "firsts," you know. Someone has to be the "first." I think Japan will see many "firsts" in the workplace going forward, so it's good to approach that positively with confidence, saying, "I'm confident. This is one of my assets! " After that, even in the Japanese government's dispatch programs, working mothers started getting hired properly.

Tozaki:So someone has to break through that barrier.

Osaki: Once you have one precedent, others start following.

Tozaki: Was it difficult working at an international organization while raising children afterward?

Osaki: Balancing work, housework, and childcare was truly tough at first. What saved me then were the words of senior moms: "Asako, raising kids is hard, right? But the really demanding years only last a few years."

They told me that if I put in the effort then, it would get easier later, and that my children would become lifelong friends and treasures. That gave me an objective perspective. My female boss was also at a stage where her children were becoming more independent, so I had a role model right in front of me.

Otsuki: Were there any institutional supports?

Osaki:The UN promotes breastfeeding until age two, so to enable staff to choose that, they covered airfare and other expenses for bringing children on business trips until age two. My daughter visited five or six countries before she turned one.

Tozaki: Having that support for bringing them along is truly helpful.

Ōsaki: Ultimately, it's an option, so the decision to bring them or not rests with each individual staff member. But I think the fact that the choice exists shows consideration.

Tozaki: Was the atmosphere conducive to using such policies?

Ōsaki: It was around the early 2000s, coinciding with a period when work-life balance systems and mechanisms were being expanded within the UN. We could take breastfeeding breaks, telework was encouraged, and if you worked extra hours each day, you could take a weekday off once every two weeks, for example. Especially our female supervisors would tell us, "Go ahead and use it. "

Tozaki: Because seeing others use it makes it easier for everyone else to use it too?

Osaki: As they said, "We didn't have these when we were starting out. But we fought hard to get these systems in place, so please use them. "

Tozaki: What incredible humanity!

◆Is Japan a country that's cold toward children and mothers?

Totsuki: Ms. Osaki, you were pregnant and gave birth in New York, then worked at an international organization. Did you feel any difference after returning to Japan?

Osaki: What surprised me was how child-rearing is treated as the mother's personal responsibility in Japan. Also, the pressure from older generations saying, " We went through tough times too, so you should endure a little." You still hear that a lot in Japan.

Tozaki: I hear it often from friends who've given birth too. There seems to be this atmosphere of, "We endured it back then, so you shouldn't have it easy."

Osaki: That's one of the biggest differences I felt upon returning to Japan. Having an environment that encourages you during that period when you're raising children and also struggling with work is actually incredibly important.

Even if various systems are in place, the cold stares, the criticism, the atmosphere that says "it's your own responsibility, so you figure it out" – that's what torments Japanese mothers the most, I think. The Japanese sense that "the mother is responsible for everything, including the child's abilities or lack thereof," feels a bit unique.

Otsuki: How about other countries?

Ōsaki: When my daughter was little, I took her to China, Thailand, Cambodia, and the Philippines. Everywhere we went, people were incredibly kind to children. Even in China, just after the year 2000 when free trade was just starting or about to start, a shop clerk approached with a really scary face. I thought, "What's this?" but then she cooed, "Baby, baby" and started soothing her (laughs).

In Thailand, at hotel restaurants, waiters and waitresses would take turns holding my child. In the Philippines, people would swarm over, exclaiming "Cute! Cute!" and making a big fuss.

Then, when we finally arrived in Tokyo, everyone suddenly became cold. Even on the train, no one would talk to us, and no one offered to help with the stroller. Every time I came back to Japan, I was shocked by the stark contrast.

Tozaki: New York is a big city too, so it has a somewhat cold impression. What do you think?

Ōsaki: New York is definitely a big city, but everyone is kind to children. Once, on the evening before Thanksgiving break, I left daycare with my then-two-year-old son and a huge load of luggage. My son had fallen asleep, so I tried to hail a taxi, but there wasn't a single empty one in sight. As I stood there, clutching the stroller and feeling utterly lost, someone got out of a taxi. I made eye contact with the driver, and we had this exchange: "Please let me get in!" "Alright, hop in."

But while I was fumbling with the heavy luggage, a young man got in. Then the driver said, " Get out! I'm letting that mother in." But the guy wouldn't get out because he'd finally managed to hail a cab. Soon a crowd gathered, and people started saying , " Of course she should get in! She's got a kid and all this luggage! " Everyone was yelling, "Get out! Get out!" " Get out! " So he got off, and everyone around helped carry my luggage, and I got on safely.

Tozaki:It's like a scene from a movie!

Ōsaki: Manhattan is that kind of city. People were really kind to children.

Tozaki:So why is Japan... It has this image of being warm, polite, and considerate, but especially in Tokyo, there's absolutely no sense of kindness towards children or moms... Especially with issues like the maternity mark causing problems.

◆Is the role of mothers too big in Japan?

Tozaki: Osaki-san, you work in development and deal with gender issues. I feel the word "mama" carries a gendered connotation, like a division of roles. Could you explain what gender actually is?

Ōsaki: Biologically defined sex refers to male and female, or male and female, with the biggest difference being reproductive function. In contrast, "gender" refers to socially and culturally constructed differences and roles. In that sense, while "pregnancy and childbirth" are biologically only possible for women, the subsequent role of "raising" the child being the mother's responsibility is a gender role, I think.

Tozaki: "Giving birth" and "raising children" are very closely linked, so it might seem like a natural progression. However, Japan is a country where women's participation in society lags significantly behind other developed nations. I think one factor contributing to this is the sheer magnitude of the child-rearing responsibility and the "good wife, wise mother" type of values that exist.

Ōsaki: Derived from the idea that "women give birth," there's also the role that "mothers raise young children." However, it's not just that. The notion that so-called "care" – for example, childcare, elder care, nursing, and "all aspects of caring for others" – is the role of women, that women are better suited for it, is precisely gender.

When such stereotypes emerge, all care-related tasks fall to women, and it expands to the point where they're expected to do it "for free" and with love. Then it becomes the societal norm that "that's just how it is."

Otsuki:So it's expected as a matter of course.

Ōsaki: Exactly. Even looking at Japan's occupational division of labor until very recently, the job titles themselves—like "ho-ba" (nursery teacher) and "kaniku-fu" (nurse)—were completely female-specific. While these titles have become gender-neutral in the last 10 to 15 years, the idea that care work is women's work was incredibly strong.

◆Why Sweden Has So Many Hands-On Fathers

Tozaki: How is it overseas?

Ōsaki: When we think of countries with advanced gender equality, the Nordic nations come to mind. But it wasn't always part of their culture. Before the Industrial Revolution, work and home were essentially one and the same. On farms, both men and women were workers. However, as industry and manufacturing developed, people started commuting to factories and offices. This meant the separation of the "wage labor" sphere from the sphere of "care work" like housework and childcare.

Tozaki: So the places where people worked became different.

Osaki: Exactly. It became the most efficient way to maintain households based on gender roles: women, as the childbearing sex, provided care at home, while men earned wages outside. However, as advanced economies diversified beyond manufacturing into service industries and knowledge-based sectors, this model became less than optimal.

Sweden was also an advanced industrial nation, so initially, this separation existed. But during the economic boom of the 1960s, the government started saying , "We don't have enough workers, so women need to work too. " They wanted women to participate in the national economy and boost GDP (Gross Domestic Product).

Otsuki: So it was for national economic reasons.

Ōsaki: At that time, women responded, "Wait, what are you talking about?" Discussions arose about who would handle the care work we had been doing unpaid in our homes and communities. They thought, "Surely you don't mean we should do care work and work outside the home too? " That's when women started demanding the government create proper policies and systems to share care work across society. This became the catalyst for women entering politics.

Tozaki: I see... So that was the progression.

Ōsaki: Sweden today has this image where all men are involved in childcare, and women manage both work and home... But that image came about through this process. Over the past few decades, they changed laws and built systems, creating the framework we see now where men and women equally share responsibility for "household finances" and "family responsibilities." In contrast , Japan is right in the middle of this transition period!

Tozaki: I see... Exactly! Even just in the last few years, I feel like the percentage of female new hires has been steadily increasing. That means more working moms, too. In that sense, this might be the toughest period for moms.

Only relatively affluent families can sustain a completely stay-at-home mom household. Yet juggling childcare and work places an enormous burden on moms, and societal attitudes aren't always supportive. Where is Japan headed from here...?

[Part 3 (Part 1) Analysis]

Why do we hear so many complaints from Japanese moms, who should theoretically have relatively supportive systems? I believe it stems from the inherent difficulty of care work centered on childcare and housework, the fact that much of this responsibility falls on moms, and the current transitional phase of the Japanese economy and the family structures it fosters. Where is Japan headed from here? What should we do? In the next installment, the second part of our discussion with Asako Osaki, we will explore concrete ways to help mothers find happiness.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Asako Osaki

Visiting Professor, Kwansei Gakuin University Director, International NGO Plan Japan

Graduated from Sophia University. Completed graduate studies at Columbia University in the United States. At the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), she was responsible for promoting gender equality and women's empowerment in developing countries, working on projects worldwide related to girls' education, employment and entrepreneurship support, promoting political participation, and conflict and disaster recovery. She gave birth to her eldest son while in graduate school and her eldest daughter while working at UNDP, also experiencing business trips with her children. Currently active as a freelance international cooperation and gender specialist. After the Great East Japan Earthquake, she utilized her international cooperation experience to support women and girls in disaster-affected areas. Drawing on her own work and parenting experiences, she is also involved in developing global talent and global education. Author of "The Theory of Girls' Happiness: A Brighter Way to Live, Starting Tomorrow" (Kodansha).

Ikumi Toga

Dentsu Inc.

Second CR Planning Bureau

Copywriter/Planner

Creative direction and copywriting form the core of my work, which also encompasses branding, business development support from a creative perspective, communication development, product development, and project management. Served as Representative of Dentsu Inc. Gal Lab from 2016 to 2020.