Note: This website was automatically translated, so some terms or nuances may not be completely accurate.

A "Global" Class That Doesn't Talk About "Global"!?

Since its establishment in October 2015, DENTSU SOKEN INC. Active Learning "What About This?" Research Lab has conducted unique collaborative and practical lessons with teachers at various schools nationwide. Rather than simply providing lesson content, the lab collaborates with teachers—the education professionals—to explore the most effective way for each specific school and class to become most "active." Each session has resulted in highly original methods and compelling stories. A researcher reports on these sessions. This time, the report comes from Kirillova Nadezhda, a researcher at the institute.

A Request for a "Global Class" from Daiichi Gakuin High School

Last summer, representatives from Daiichi Gakuin High School approached me with an intriguing proposal: they wanted to collaborate on a "global studies" class. Global studies? It sounded deceptively simple, yet question marks immediately filled my head. Was it a class teaching foreign languages? Introducing various overseas cultures? Or teaching how to succeed abroad? While none of these were wrong, each felt slightly off.

"Unease" – this might be the most crucial keyword for learning about "global." That's it! Let's turn this "unease" into the class itself!

Uneasiness: What exactly is "global"? Who does it refer to?

"Global" seems to point to some single "universal standard," but it doesn't actually refer to anything concrete. Because, I think, "global" is a collection of diverse personalities and ways of thinking.

By learning about those individualities and ways of thinking, you realize different individualities and ways of thinking exist. Within that, you can also notice commonalities. To do that, you first need to know what kind of individuality you have and what kind of thoughts you hold. Otherwise, you can't even notice where the differences and commonalities lie. I thought that might be the gateway to "global."

Further discomfort: Japan is global too, though...

In Japan, "global" often means "everything outside Japan," but for me, Japan is also "global." And it's a very distinctive kind of "global." If that's the case, could we turn this around? By looking at Japan from my perspective, could we make Japanese high school students aware of that "discomfort"?

Hypothesis for this project

Couldn't using the familiar place called "Japan" as an entry point drastically lower the barrier to "global"?

I decided to test this hypothesis during a meeting with Daiichi Gakuin High School. "Hey everyone, this might be sudden, but what exactly are those 'name tags' you often see in Japanese elementary schools for?" The adults looked a bit surprised and said, "Huh? They don't have those overseas?"

Everyone present had worn name tags in elementary school, but it was so commonplace that no one had ever considered why. Nor that some countries don't use them. Okay, my hypothesis might not be so far off after all.

Thus, through four lessons, we developed a program at Daiichi Gakuin High School—a correspondence school with 35 campuses nationwide—that lets students experience "global" from a slightly different angle.

The "Discomfort" Starts with Appearance

You're probably wondering what kind of class it became. But before that, let's start by introducing a bit about the sense of dissonance outside the class itself. This time, the "dissonance" wasn't designed just for the class content.

Since Daiichi Gakuin is a correspondence school, instructors and students aren't in the same room. Classes are delivered via 60-inch monitors at each campus. Even with interesting content, it's tough to keep students engaged for 90 minutes if the teacher just mechanically explains slides.

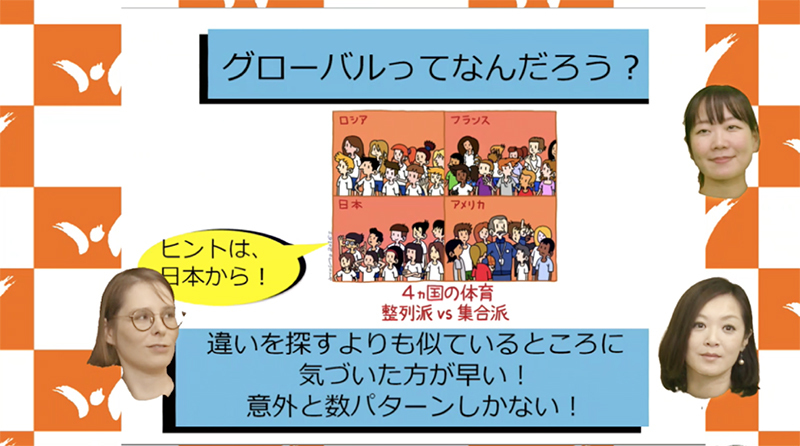

Therefore, instead of having just one instructor, we decided to have three: one to introduce the "unfamiliar feeling," one to make witty remarks, and one to connect with Daiichi Gakuin High School. By dividing their roles, we created a format similar to an interactive talk show, and we also challenged ourselves to have only the faces of the three instructors appear on the slides. The instructors wore green ponchos, which were prototyped repeatedly, against a green background and taught the class. The class was broadcast to each campus using three cameras.

First Period: Japan is this interesting!

Japanese schools and streets are overflowing with "interesting" things. For example, in schools: name tags, headbands, disposable textbooks, cleaning time. In the streets: white taxi seats, toilet slippers, orderly boarding, traffic light colors. In Japan, these are all normal, but to me, each one felt quite "strange."

Don't you remember your classmates' names? Why use headbands when you have name tags? Doodling in textbooks...? We share each of these observations with the students.

I asked them in real time why things were done that way. We compared the various answers together. We realized that even within Japan, there are many different personalities and ways of thinking. Together, we experienced discovering "global" right around us. What's "normal" for someone can be "strange" for someone else.

Lesson 2: "Global!? Japan and overseas are the same!"

When encountering "global," alongside the "strangeness" of differences, there exists the "strangeness" of similarities. Methods and forms may differ, but actually, the world has quite a lot of similar places and things. For example, in schools: school slogans, uniforms, packed lunches or school lunches. In towns: festivals, foods with distinctive flavors like natto or Australia's Vegemite, Halloween and Obon, the fact that more countries require removing shoes...

As the saying goes, "Birds of a feather flock together." Discovering similarities is a shorter path to "global" than just looking for differences. It's that "strange feeling" of realizing, "Huh, this is actually pretty 'normal'."

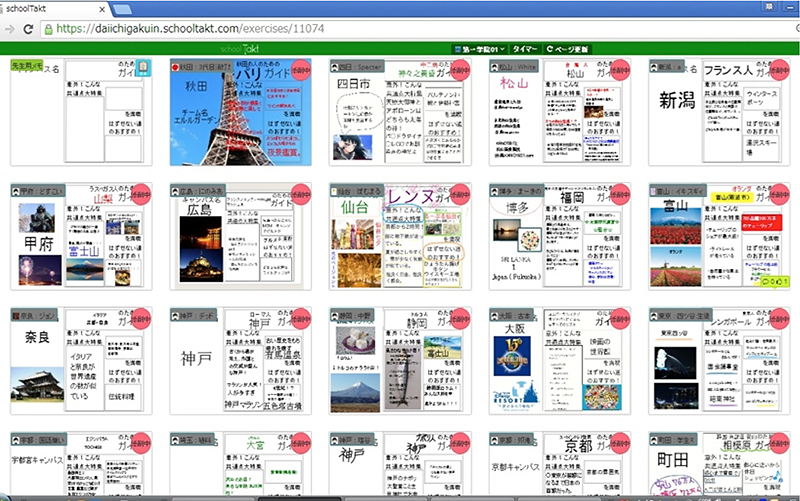

3rd Period: Workshop "Your City Guidebook for People Living Abroad"

Just as we were getting used to the idea of "global," it was time for the workshop. The third session was practice for diving into the "global" world ourselves. The assignment: "Find an overseas city similar to your own and create a guidebook for people living in that city about your hometown."

The 35 campuses nationwide are like small "globes." It starts with finding what makes each town unique, then searching for overseas towns that share that same "interestingness." If they're all the same, you won't feel motivated to visit them. You can't create an interesting guidebook without knowing the differences. So, we also explore the differences. After 90 minutes, 35 guidebooks were completed.

4th Period: Critique Reading all 35 guidebooks together

35 guidebooks revealing the charms of 35 Japanese cities and 35 overseas cities from slightly unconventional angles. They offered encounters with foreign cities, of course, but also many new perspectives on familiar Japanese cities. By discovering each one, the high school students unconsciously plunged into the "global." And it may have become a trigger for them to want to embark on a "global" journey more than ever before.

The Grand Prix winner that day was Kumamoto Campus's "Kumamoto Guide for Icelanders." Focusing on the fact that both Kumamoto and Iceland are "lands of fire," it proposed enjoying the shared attractions of both: magnificent nature and hot springs. Precisely because even long-time residents of Japan hadn't deeply considered Kumamoto as a land of fire, it became the most popular guidebook among both instructors and students.

Another guidebook that gained popularity among instructors was the Hiroshima Campus's "Guidebook for Residents of the Manche Department in Normandy, France." It highlights the shared World Heritage status of Itsukushima Shrine and Mont Saint-Michel as sites floating in the sea. It points out commonalities like eating conger eel rice when visiting Miyajima and omelettes when visiting Mont Saint-Michel, as well as the beautiful nighttime illumination at both locations. This approach makes you want to visit again, even if you've been before.

What exactly is "global"? Learning languages to communicate with people worldwide or going abroad to experience "global" things are certainly very important. But perhaps the essence of "global" begins with understanding the ways of thinking of various people and why they act as they do.

This time, I happened to teach from this slightly unconventional angle, but there must be many more ways to approach learning about "global." For example, if you suddenly teach elementary school students about "overseas" or "English," they might feel it's something distant from their own lives. For people who've lost touch with "global" in their daily lives, making it relevant to themselves again can feel like a high hurdle. But I thought that by changing the approach slightly, like starting with things close to home, we could create opportunities to connect with "global."

Announcement: In February of this year, I received the Judges' Special Award at the JICA Global Education Contest.

Was this article helpful?

Newsletter registration is here

We select and publish important news every day

For inquiries about this article

Back Numbers

Author

Kirillova Nadezhda

Dentsu Inc.

Business D&A Division Team B

Creative Director

Born in Leningrad, USSR (at the time). Raised in six countries. After joining Dentsu Inc., worked as a creative across diverse fields, handling a wide range of domestic and international projects. Recipient of numerous awards. Member of the Active Learning "How About This?" Research Institute.