Titled "Quit, Conform, or Change," this series explores new "possibilities for large corporations" through events centered on themes related to corporate transformation. Starting with the third installment, we will examine these possibilities by featuring case studies of large corporations that have challenged transformation, selected from companies affiliated with ONE JAPAN volunteer groups, and interviewing the individuals involved.

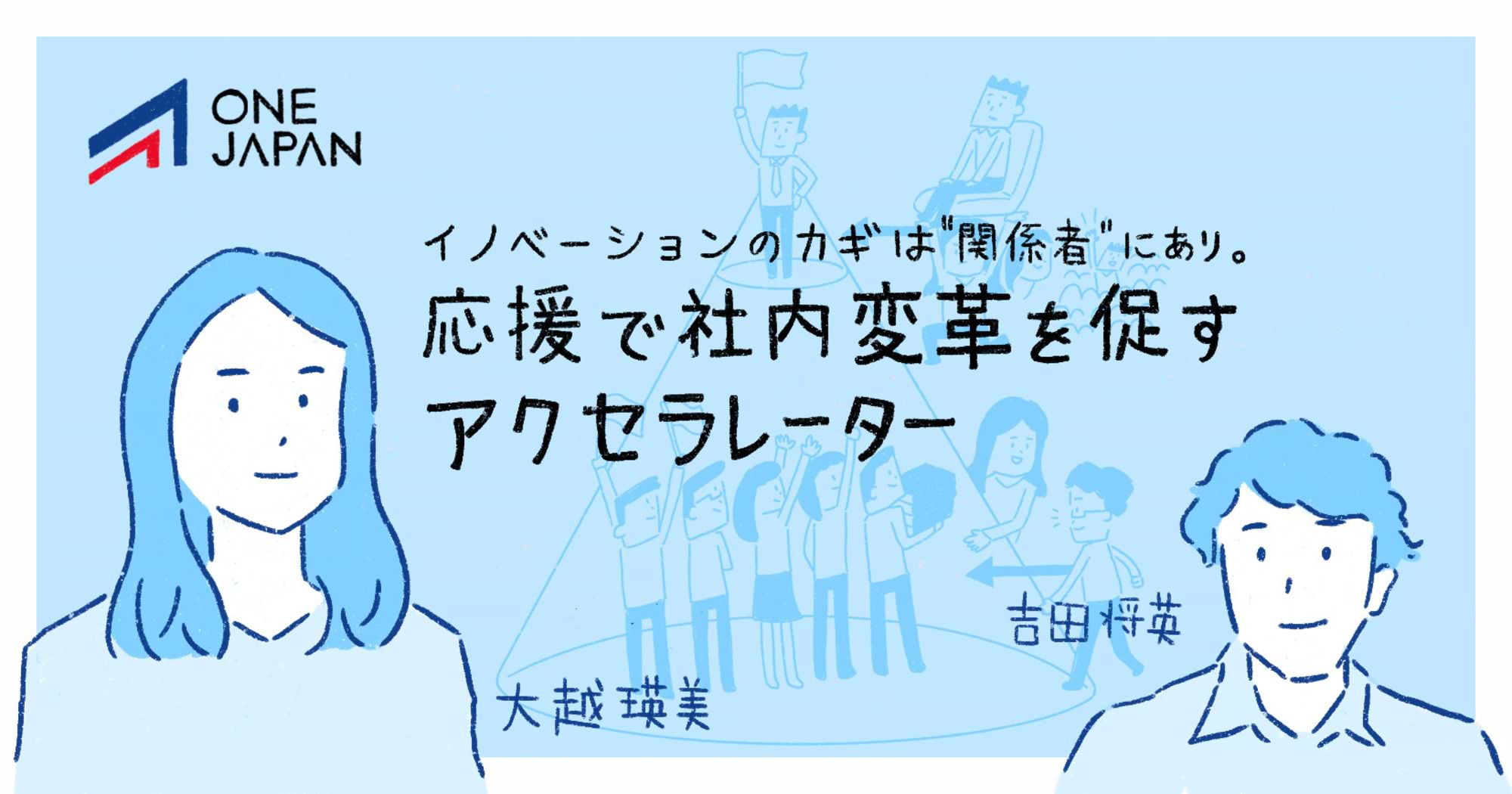

ONE JAPAN: A practical community gathering corporate volunteer groups centered around young and mid-career employees

This time, we interviewed Mari Kawasaki, who serves as a project manager supporting business operations at Nomura Research Institute's (NRI) overseas locations while also working as a "Digital Buzz Creator" to foster human connections in the new normal era.

In this era of individuality, she advocates the "Second Penguin Approach" as an essential element for both individuals and organizations to thrive. Masahide Yoshida, representing Dentsu Inc. Youth Research Department and a member of ONE JAPAN, spoke with her.

Online is a double-edged sword of convenience and impersonality. How can we evoke a sense of humanity?

Yoshida: Ms. Kawasaki, you've been actively promoting "Digital × Space Creation" since last year. What led you to this?

Kawasaki: The major catalyst was the pandemic. It fundamentally changed human connections, both inside and outside companies. In a world where people couldn't easily meet, I started thinking about how to express the immediacy and warmth of real-life interactions.

Personally, I've been fascinated by digital technology since high school, when I was deeply moved by Philip K. Dick's "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" While I don't develop IT services, I often encounter new technologies. As a user, I think about how to leverage digital technology for space creation.

Yoshida: With Zoom, which saw explosive user growth last year, I get the impression that you're adept at precisely utilizing tools accessible to anyone – whether it's running events that fully leverage its features, or sharing that know-how on social media and user-generated platforms.

On the other hand, watching Kawasaki-san handle the technical aspects at ONE JAPAN events, I sensed not only solid skills but also a strong awareness of what truly matters as a person.

Kawasaki: I love digital technology, but I also really love the human touch. During events, I enjoy watching participants' reactions and keep an eye on the video feed the whole time. Based on their responses, I might steer the conversation as a facilitator or follow up via chat or private messages. I always run events mindful of "what kind of atmosphere I want to create" and "what kind of afterglow I want to leave." I also place great importance on designing communication not just during the event, but before and after it. I consider what actions in each phase will best foster connections between participants afterward.

Yoshida: In terms of valuing people, how do you think the pandemic changed communication and connection? For example, looking at work communication, the traditional seating hierarchy in conference rooms disappeared with remote meetings.

Kawasaki: I think the loss of the stage and hierarchical seating has fostered a greater sense of flatness. Even during reports or presentations, the focus is now equally on each individual, rather than just one person standing in front of everyone.

Another interesting change is the liberation from physical space. Previously, securing a location and gathering people there was the norm. Now, you can participate in events from anywhere in Japan or the world. Participant diversity has also expanded. I believe this will become the new norm.

Depending on the industry, some people have actually decided to relocate because the need to come into the office disappeared. I feel this phenomenon symbolizes an era where the spotlight is shifting from companies to individuals. I also reconsidered where I live and how I use my time, and it really forced me to confront the question of "how do I live as an individual?"

Yoshida: Regarding the ease of personal choice, I imagine some perceive it as freedom, while others find it frightening. For instance, when working from home becomes the norm, it can conversely lead to feelings of gloom, and there's an aspect where new employees could arguably feel neglected. How do you think we can contribute to community building in response to this situation?

Kawasaki: I also feel there are challenges with the "shallow relationships" born from online interactions. While countless online events emerged this past year, how many actually made me want to meet someone in person afterward? This ties into the atmosphere we discussed earlier, both during and after events. While we can now connect broadly across physical spaces, pressing the end button instantly returns us to an environment where we might not speak a single word. There are no chance encounters like in an office. As initial meetings increasingly shift online, I'm conscious of creating mechanisms that make people want to keep talking and maintain connections after meetings or events.

The new "anchor" companies navigating the new normal should possess

Yoshida: Reflecting on the new lifestyle, I found myself wondering: Were we really that close when we commuted to the office? Even people sitting next to each other in the office might chat casually if they were nearby, but perhaps we weren't actually that close. When you look at a company as a community where conversation happens even without particularly close relationships, what function do you think it served?

Kawasaki: Companies provide individual roles—like job titles and positions—and the relationships that come with them.

I think it was precisely because of these roles and relationships that, as Mr. Yoshida mentioned, "even without being close friends," a certain level of conversation naturally occurred. Furthermore, commuting to the office was the standard way of working until now. By commuting and sharing time and space, there were many opportunities to be aware of others, creating an environment where conversation was more likely to happen.

Now, however, with the absence of commuting, sharing time and space has become difficult, making it harder to be mindful of the people we work with. Furthermore, in these unprecedented circumstances where it's hard to feel mentally at ease, people are often just trying their best to adapt to this new environment. It's common to be too preoccupied to think about how to interact with others online.

In that sense, I believe coming into the office held meaning beyond just the constraints of time and space. It certainly served as a key element in fostering community. As I work on creating digital spaces, I'm also contemplating what new key elements will emerge now that coming into the office is no longer the norm.

Yoshida: If we consider the past era as one where companies used the office space as a anchor to bring people together, what will replace that physical space in the next era? I feel it's crucial whether companies are raising a banner – something like the purpose or mission we hear about recently – that employees want to follow. As Mr. Ogoshi from Ricoh pointed out in a previous discussion, it doesn't necessarily require a mandatory "will." If that were the case, every employee would have to become an entrepreneur, and conversely, the organization itself wouldn't function.

Kawasaki: Exactly, not everyone needs to wave the flag. What matters is finding and growing the "overlap" between an individual's core values and what they hold dear, and the purpose or mission of the company or organization.

Even without that will, simply aligning what you value with your current company or organization allows you to think and act in your own way. While involving others and taking the lead, or creating new businesses or organizations, are valid approaches, the way people move forward varies. I hope companies foster environments where people can act in ways that suit their strengths—whether that's supporting others, spreading ideas widely, or other approaches.

Yoshida: It's perfectly fine to have followers or second penguins. Sometimes, through community connections, these individuals can suddenly transform. That's precisely why communities are so compelling—they reveal this kind of dynamism.

Not just one brave soul taking on the challenge, but for "everyone" to move forward just one millimeter.

Yoshida: I'd like to hear more about the "Age of the Individual." In today's society, business leaders are often equated with success, and many of them believe their macho theories can be applied to the entire organization. They say things like, "Don't you have something you want to do?" or "Just do it! You can do it if you try!"

Yoshida: I'd like to hear more about the "Age of the Individual." In today's society, business leaders are often equated with success, and many of them believe their macho theories can be applied to the entire organization. They say things like, "Don't you have something you want to do?" or "Just do it! You can do it if you try!"

I think those saying it have good intentions, wanting people to achieve self-realization. But when people follow along while harboring doubts, it can create so-called stragglers. Realizing one's own will isn't the only measure of society; there should also be ways to collectively grow a powerful energy ball. Even if it gets mocked as a "buddy club."

Kawasaki: I understand because I'm not the type to pursue my own will either. Now, I've found my place at ONE JAPAN, surrounded by passionate colleagues striving to transform large corporations. But at the first event I was invited to, the people who were constantly driven by their will were so dazzling that I thought, "There's no place for me here, I want to go home" (laughs). What changed that feeling was finding my "connection point" with ONE JAPAN and being able to "just give it a try."

My company seniors were already involved in running ONE JAPAN, so helping out felt natural. As I got involved, I noticed various issues, proposed improvements, put them into practice, noticed more... and this cycle of action started spinning. Through doing, I built trust with other ONE JAPAN members, gained my own successes, found things I wanted to challenge, new people joined... and before I knew it, I was fully immersed on the operational side (laughs). By taking action, even small steps, I found a place among colleagues and achieved "self-actualization" – something I never thought possible.

Another big thing was recognizing my strengths through practice and learning to use them consciously. My main job is project management, but I've developed what you might call "noticing skills" – like handling overall scheduling or stepping in to push things along when progress slows. I'm not the type to push my expertise or leadership skills to the forefront, but I feel like I'm in a position that's necessary for the organization.

Yoshida: From a company's perspective, someone who picks up the slack is invaluable. Especially for those not in the first-mover position, it can be unclear how far to get involved. For the second and subsequent penguins to shine, I think it's crucial for people like Kawasaki-san to serve as a compass for those who "don't know what to do."

Kawasaki: I feel that even when leading a community. Earlier we talked about "touchpoints." I consciously focus on providing accessible hooks for participants and ensuring organizers consistently convey the message, "We want everyone to get involved." To put it bluntly, if the first penguin appears overly competitive from the outside, it can make it harder for others to follow. Sometimes, the first person diving into a difficult spot might inadvertently steer the second and subsequent penguins in the wrong direction.

Yoshida: During the heyday of mass advertising, only "amazing people" appeared in the media. But now, with social media widespread, it's an era where anyone can participate in the media. If people assume only those who can dive into difficult areas can reach the spotlight, everyone will hesitate.

But if you look closely, those who stand out in information sharing aren't necessarily doing things only they can do. I see it less as special ability or insight, and more as the act of sharing itself being valued. Shifting from the mass media mindset of "only amazing people" to a social media mindset could lower the barrier for those thinking, "I'm not a first penguin."

The growing importance of "second-to-last" players in this era of individuality

Kawasaki: If this mindset takes hold, individuals will shine more easily, and it will undoubtedly benefit organizations too. Earlier I mentioned "just try it first," but I often say, "move even just one millimeter." The word "move" can feel like a high hurdle, but it's okay to start by simply following someone else. It's fine if you realize you've moved one millimeter without even noticing. The key is not to frame it as "move even just one millimeter."

If the first penguin is too perfect, it can intimidate others. The trick is to create space for that one-millimeter movement in various places. Deliberately showing imperfection is one way to do that.

Yoshida: So there can be many different forms of leadership and first penguins.

Kawasaki: To put it another way, you don't have to force yourself to be the first penguin. While a perfect leader can break through a situation, that shouldn't be the only, absolute model. It's good for leaders to come in different types. Some leaders excel at rallying people and pulling them along, while others are skilled at finding the intersection between the organization or team's direction and the members' aspirations and desires, then supporting that. I think it's crucial for those in leadership positions, starting with the top of the company, to understand that it's not a binary choice of whether someone can or cannot become a success.

Yoshida: In the sense that those who aren't first are important, I think ONE JAPAN embodies a new way of connecting. There are about 50 member groups (volunteer groups within companies), and nine people—co-representatives and secretaries—play central roles without any hierarchy or vested interests. Managing an organization without rank or a chain of command might be tough, but I see it as management for a future-oriented organization. People complain about top-down structures, but flat structures surely have their challenges too.

Kawasaki: That's right. Since it's a community of volunteers, everyone has their own convictions. Precisely because it's not a company, individual beliefs come to the forefront. Not everyone necessarily faces the same direction, and no single viewpoint is inherently "right." In that sense, it presents challenges not found in top-down structures. But I think it's healthy because everyone understands that these difficulties stem from the very passion driving us.

Yoshida: What concerns me is whether "everyone can do as they please" truly works. In traditional large corporate structures, things like dress codes, standardized work processes, and seals were default assumptions of what was right. But some people are starting to realize that those notions of rightness and common sense were illusions, especially during the pandemic.

Kawasaki: In that sense, it brings us back to what we discussed earlier about large corporations: rather than relying on the unique sense of justice inherent to a specific space or place, it's crucial to anchor ourselves in our aspirations.

Yoshida: As we discussed in our previous conversation, the essence of the "Age of the Individual" isn't about climbing a mountain faster than others, but about finding the mountain you want to climb. While you might be a First Penguin, Kawasaki-san, I sense you aren't fundamentally swayed because your own value standards are solid. Of course, the very act of demanding "You must find your value standards" or "What's your foundation?" can itself be a form of "will harassment."

Kawasaki: To find that foundation, taking even a tiny step forward is crucial. Not a centimeter, just a millimeter. And for those in a position to welcome second penguins, providing that hook to take that millimeter step is vital. I started on the receiving end of that welcome, but that tiny step eventually led me to become the one extending the welcome.