─Trend #1 from the 16-Country Sustainable Lifestyle Awareness Survey─

In July 2021, the Global Business Center and DENTSU SOKEN INC. jointly conducted the "Sustainable Lifestyle Awareness Survey 2021" targeting 12 countries (Japan, Germany, UK, USA, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam). An additional survey was conducted in October targeting 4 countries (Brazil, Australia, South Korea, Sweden).

This report focuses on the findings from the 16 countries, examining "Awareness of Personal Responsibility for Sustainability" and "How Much Action Can Be Taken?"

Does a country's maturity lead to weaker personal responsibility?

First, let's look at the overall composition of "sustainability-related consumption intent × social activity" across 16 countries.

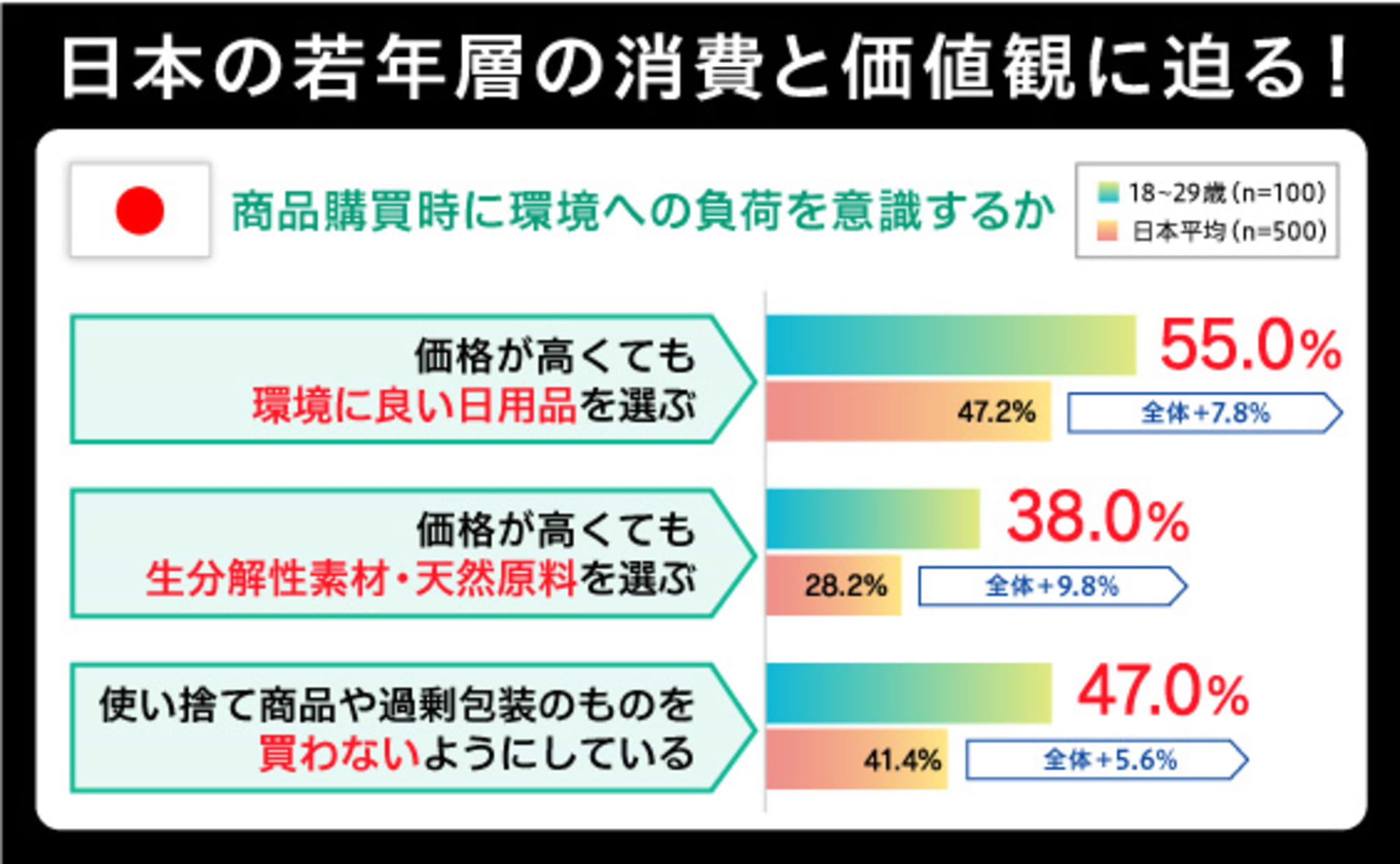

The vertical axis of the matrix below represents consumption willingness: whether people choose "environmentally friendly daily goods even if they cost more" or "daily goods that are cheaper than environmentally friendly ones." The horizontal axis shows whether people participate in or support social activities like donations, signing petitions, or sharing information.

In this paper, we define accepting environmental conservation costs through consumption as "environmental premium consumption" and actions like donations, signing petitions, or sharing information as "social activity support."

Among these four groups, the clear indicator that divided the 16 countries was actually the percentage of people who were "indifferent to both."

Japan, which ranks at the bottom of the 16 countries, has a strikingly high proportion of indifferent people at 40%, and is characterized by a low total proportion of social activity support (shown in green and pink on the graph) at 28.0%, which is less than 30%.

In contrast, the top-ranked ASEAN countries, India, and China have a low percentage of indifferent people, with the majority supporting social activities.

The middle group, including Europe and the United States, had an indifference rate of about 30%, with 30-50% supporting social activities.

Among them is Sweden, a Nordic country that has been in the top three of the SDGs rankings for many years. Sweden stands out for its high level of knowledge, such as people's understanding of sustainability terminology, and its top-level actions, such as the collection of unwanted items. However, this graph shows that Sweden, like other economically advanced countries, does not have a high level of consumer awareness or social activity related to sustainability.

Many Asian countries, benefiting from a younger population structure and ongoing economic growth, are proactive about change. They are positive about supporting social activities aimed at creating a better world and show little negative sentiment toward environmental premium consumption.

Conversely, in Europe, Japan, and South Korea, there is a stronger tendency to contribute as consumers through environmental premium consumption rather than supporting social activities.

Even in countries with well-established social and economic foundations and advanced environmental conservation efforts, those experiencing slower economic growth in recent years may find it harder to envision "change for the better."

Furthermore, this survey found no correlation between higher household income and willingness to engage in environmental premium consumption across all countries. It seems that uncertainty about the future (anxiety about future economic growth) is what makes people hesitate to spend money or time on environmental conservation.

Why is Japan's environmental awareness high, yet its actions remain only "occasional"?

Based on the results of an additional survey conducted in December 2021 across four countries—the US, UK, South Korea, and Japan—we will now examine environmental awareness and actions.

Is there a difference between countries in the desire itself to "take environmentally friendly actions," or in "how much environmentally friendly action is actually being taken"? If there is a gap on these two points, we will compare "why people are not taking action."

To state the conclusion first: the desire to "do environmentally friendly things" is high in every country. There are differences between countries in "actual actions taken," and the top "barriers preventing action" are the same across all countries.

First, the desire to "do environmentally friendly things" is high in every country, ranging from 80% to 90%, though there are slight differences between nations.

Next, regarding "actual actions taken," for waste sorting, a high proportion in each country—70-80%—reported doing it "daily or most days," indicating it had become a habit. On the other hand, for reducing CO2 at home, the UK had the highest rate at 53.7%, while other countries hovered around 40%, showing it is not yet habitual.

Regarding consumption behaviors aimed at reducing environmental impact, habits are established among 50-60% of people in South Korea, the US, and the UK. However, Japan stands out with a notably lower rate of habit formation, around 30%, where "occasionally" is the most common response.

Regarding climate change response and animal protection, within the trend of reducing meat consumption, concepts like "#SometimesVegan" and "#PartTimeVegan" have emerged. These promote not eliminating all meat and fish entirely, but consciously incorporating them occasionally while enjoying the experience. These terms are posted on social media and have gained support from celebrities.

This movement to spread environmentally friendly practices alongside a sense of style resembles the emergence of various eco-bags from luxury brands a decade ago. Back then, eco-bags became a mainstream item, something everyone carried. However, for daily use to become established, it required legal measures like fines or fees in various countries. Similarly, for it to become a habit, some form of regulation might ultimately be necessary. Plant-based meat alternatives are now sold in many supermarkets, but becoming a "daily use" item for the majority still seems challenging. As of July 2021, 29.0% of Japanese people aged 18-29 had tried "plant-based meat."

Finally, examining the "barriers preventing action," the four factors below were the main reasons cited by over 30% of respondents in every country.

Among these, "Environmentally conscious products are too expensive," "I can't tell if a product is truly environmentally conscious," and "The variety and choices of environmentally conscious products are limited" are areas where corporate initiatives are expected.

Meanwhile, Japan stood out with a significantly higher percentage (48.7%) for the consumer-side factor: "It is difficult to live without using cheap and convenient products."

In Japan, corporate efforts to make high-quality, convenient products widely available at low prices have been considered a virtue, and the idea of "working harder than others to achieve economic success" has motivated the workforce. Consumers have also become accustomed to the idea that "buying new things as cheaply as possible is smart and makes life enjoyable."

However, if we eradicate illegal labor, use green power, and maintain supply chains that do not burden the environment or socially vulnerable people, product prices will rise. If the majority of consumers continue to base their purchases solely on price, the spread of environmentally and socially conscious products and services may be delayed.

Although resistance to price increases is likely to be strong, it is necessary to shift to a model where satisfaction is achieved through reduced consumption, even at a higher cost. The idea of decoupling environmental conservation from economic growth may be necessary not only for countries and companies, but also for individual consumers, in order to feel a sense of richness that is not based solely on economic factors. Of course, it is equally important for countries and companies to guarantee the foundations of people's livelihoods, not just raise awareness.

In recent years, the spread of COVID-19 has made "reevaluating our lives amid restricted actions and economies" increasingly acceptable. The question is whether we can shift our focus from emphasizing economic gains and losses to valuing ways of life and virtues. Are nations, corporations, and individuals united in letting go of "cheap and good things" (which are not necessarily good for the environment or society)?