OODA (pronounced "woo-da") is gaining attention as a "decision-making model" that guides solutions to the rapidly changing challenges of modern business. It proves effective not only for organizational development and management strategy but also for branding and marketing.

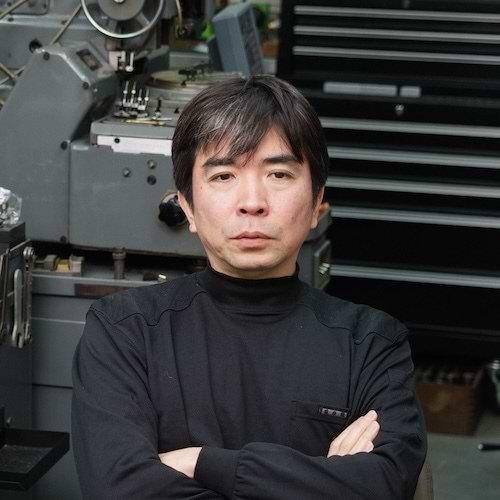

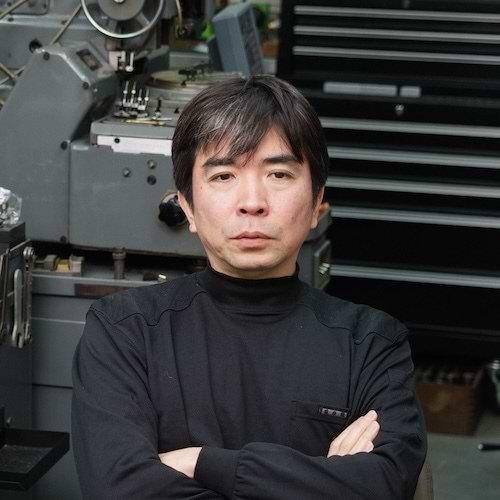

In this series exploring the appeal of OODA from multiple angles, our guest this time is Mr. Jiro Katayama, founder of the watch brand " Otsuka Lowtech." The high-quality, uniquely individual products born in a small factory in Otsuka, Tokyo, attract orders from around the world far exceeding production capacity, captivating even the most discerning watch enthusiasts. The brand concept of Otsuka Lowtech and Mr. Katayama's approach to manufacturing appear to share common ground with OODA.

We present a two-part interview with Aaron Zou, author of " OODA Loop Leadership: The World's Most Powerful Doctrine " (Shuwa System).

【What is OODA?】

A decision-making and action process proposed by John Boyd, a former U.S. Air Force Colonel and fighter pilot. The term OODA is an acronym for Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. Its purpose is to consistently take the best course of action in constantly changing, unpredictable situations. In Western business and marketing, OODA is recognized as an indispensable decision-making process alongside the traditional PDCA cycle. ( Learn more here ).

Combining watchmaking techniques learned from YouTube with expertise cultivated through Japanese craftsmanship to create truly unique products

Aaron: Otsuka Lowtech is a watch brand now attracting global attention. Its unique mechanisms have earned it a place in the Swiss International Watch Museum, and its technical value has led to preservation at the National Museum of Nature and Science. Personally, I'm a huge fan of the brand. While researching it, I began to suspect that Mr. Katayama might be an OODA practitioner. That's why I wanted to hear more about it in detail this time.

Katayama: I wasn't familiar with the term OODA, but I've rarely had the chance to speak at length with people who cherish my watches. I was looking forward to hearing how they perceive the brand.

Aaron: Thank you. Could you briefly share your background and how you launched the brand?

Katayama: After graduating from design school, I worked as a car designer at a Toyota-affiliated company, involved in the exterior design of models like the Altezza and Funcargo. Then, on a whim, I quit that job. I started doing product design work while moonlighting as a mechanic at a car shop, and in 2000, I became an independent product designer. Back then, I worked on all kinds of products across industries – helmets, home appliances, medical devices, you name it.

One day, I happened to acquire a bench lathe. I started metalworking in my spare time between my main job. It turned out to be quite interesting, and I got hooked. But since I was working in a corner of my kitchen, I couldn't make large things like automobiles. So, I decided to aim for smaller items. That's when I started making watch cases around 2008.

Aaron: With established Swiss brands, you have this strong image of them being made in workshop-like castles, right? Starting from a kitchen in a downtown house – that story alone makes it truly one-of-a-kind.

Katayama: Honestly, I did want to make them in a castle-like place (laughs). But back then, I didn't know about those famous watch brands, and I had absolutely no idea how to make watches. I started by searching online, watching YouTube videos, and just copying what I saw. I remember thinking, "Swiss watchmakers sure dress stylishly" (laughs). Now I've just accepted it and work in overalls.

Aaron: That's precisely what makes it great. To Westerners, the fact it's made in a small town workshop—a scene that embodies the good old days of Japanese craftsmanship—conveys an Oriental quality and uniqueness absent from mainstream luxury brands. That story perfectly complements the product's form and details.

Katayama: It's gratifying to hear that kind of praise. But perhaps it was fortunate that I didn't know the established theories of watchmaking—I didn't have preconceived notions about how things "should" be.

Repeatedly cycling through "Observation" → "Judgment" → "Decision" → "Action" leads to the ideal idea

Aaron: How did you acquire the skills necessary to make watches?

Katayama: Web searches, YouTube, and books. For example, I'd watch videos explaining how to make mechanical watches over and over. First, I'd gather tools and parts and try making one by imitating what I saw. Repeating this process, ideas would emerge like, "I'd want to do this differently," or "This feels more natural." Then I'd test those ideas. Through constant trial and error, I guess I just happened to get it right. Honestly, I still don't think I fully understand the correct way to make watches.

Aaron: That's precisely what I'd call an OODA-like thought process. Rather than acting based on meticulous plans or theories, you're constantly accessing new information, observing things, making on-the-spot, flexible judgments, and implementing the best course of action each time—repeating that cycle. By repeating that process, you ultimately ended up creating an innovative product that made its mark in watchmaking history.

Katayama: Now that you mention it, working alone probably allowed for quick cycles of trial and error, which was beneficial. I imagine larger watchmakers take much longer for even a single decision.

Aaron: Exactly. In OODA, we also emphasize "delegation of authority" as crucial for speeding up decision-making. As an independent watchmaker, Mr. Katayama is a prime example of this. Even within an organization, granting trusted members a degree of discretion can significantly accelerate decision-making.

Dialogue with things that strike a chord becomes an "unconventional strategy" for watchmaking theory.

Aaron: In today's rapidly changing business environment, "orthodox strategies" that once reliably generated profits can become ineffective. In such situations, surprising "unorthodox strategies" that make you think "Why didn't I think of that?" can become breakthroughs. I feel Otsuka Lowtech's innovative mechanisms and designs are precisely such "unorthodox strategies" against watchmaking theory. Is there anything you consciously do to foster creativity?

Katayama: I don't have any special preparation or plan, but whether it's watches or other things, I take photos of or keep nearby items that I instantly like. When I'm thinking about design, I look at or touch them and ask myself: Why did I think this was cool? How does this mechanism work?

Aaron: Is that like honing your sensibility?

Katayama: Yes. There's a phrase, "striking a chord." It's when something moves you without you knowing why, when you just think, "That's good." You can't clearly define the reason, and that's why design is so interesting. Also, I personally love mid-20th century lathes, gears, and industrial machinery. I often draw inspiration from their forms, details, and textures.

Aaron: Indeed, Otsuka Lowtech watches are incredibly intricate and mechanical. Yet, they don't represent cutting-edge mechanics like Swiss mechanical watches. What's truly outstanding is how they express the essence of Japanese craftsmanship from the era of high economic growth through their design.

Katayama: I'm delighted you see it that way.

In the second part, we'll explain the products crafted by Otsuka Lowtech and the "New Luxury Strategy" glimpsed through their manufacturing approach.