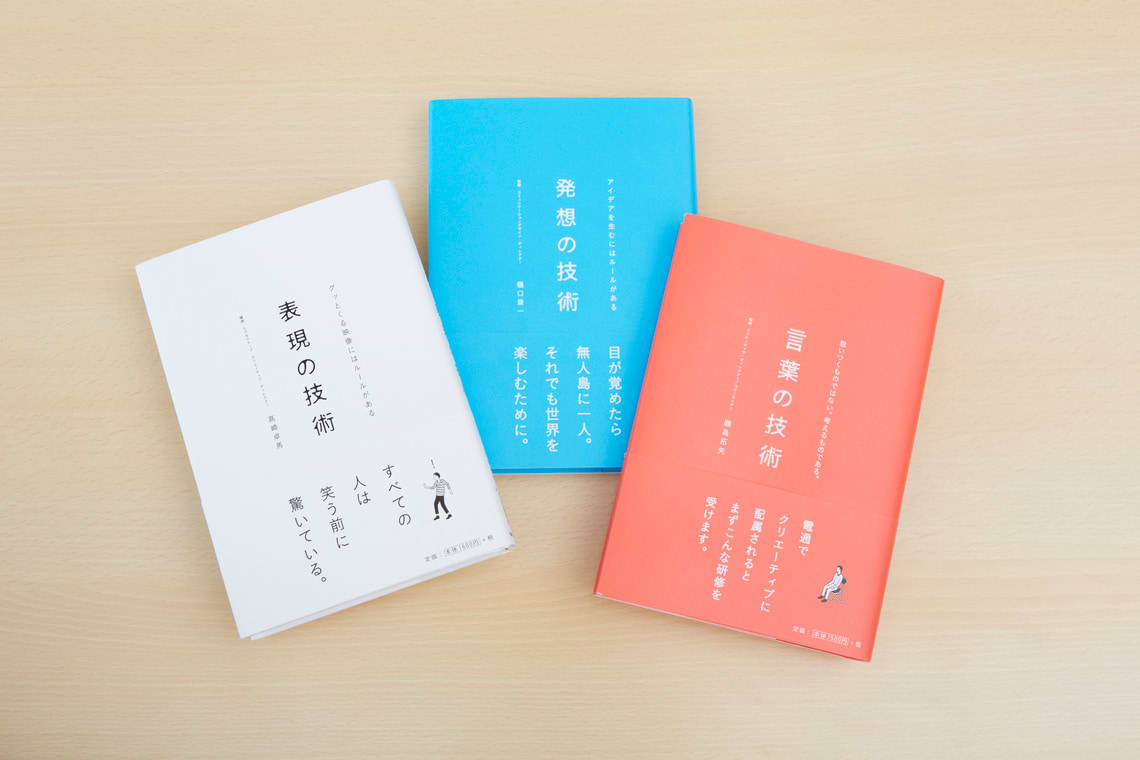

Books published by Dentsu Inc .: "The Art of Expression" (by Takuma Takasaki), "The Art of Ideation" (by Keiichi Higuchi), "The Art of Words" (by Takuya Isoshima). The three volumes of the "Technique Series"—written by authors from different specialties: CM Planner (Takasaki), Communication Design Director (Higuchi), and Copywriter (Isoshima)—are gaining recognition as universal treatises on technique, even beyond advertising circles. What the three authors share is their emphasis on the importance of "thinking." This time, they engaged in a roundtable discussion themed around "the technique of thinking," reflecting on their respective works.

All three are climbing toward the same point

Takasaki: When I created this book, I didn't really envision it becoming a series like this. That's why I didn't want to narrow the scope and ended up giving it a broad title. Now that we have this lineup, my book should have been titled "The Art of Film." I chose the title "Technique" because most advertising-related books become wildly outdated after just a few years. I really wanted to avoid that. I didn't just want to poke at our weak spots – our nervousness about changes in media and society – I wanted to write about how to build a core that isn't swayed by such things. In that sense, I'm writing about ordinary things. I deliberately aimed for the universal.

Higuchi: I see.

Takasaki: After reading all three books, it's strangely similar, isn't it? The aftertaste. The visual route, Higuchi-kun's strategic route, and Isoshima-san's copywriting route. Each route is different, but it's like as the mountain's elevation increases, the scenery you see fundamentally starts to resemble each other.

Isoshima: That's right.

Isoshima: That's right.

Higuchi: What struck me as frighteningly similar between the two books is that it all boils down to "ultimately, you just have to think." In strategy and planning workshops, you often see this box-filling format thinking—like "fill in the boxes and you'll have a plan." But good plans don't come from that. I wanted to break that mindset of trying to shortcut to the goal without actually thinking about the plan itself. That's why in The Art of Ideation, I wrote about anti-format thinking and how to build plans.

Isoshima: For copywriters, there are definitely specific techniques. Like, when asking someone out, "Want to go on a date?" is less effective than "Pizza or pasta? Which do you want?" because women tend to choose one or the other (laughs). Or how "white sneakers" is commonplace, but combining it with a jarring word like "glowing sneakers" creates something new. These techniques are concrete and useful, but relying solely on them feels a bit hollow. That's why in The Art of Words, I wanted to convey the technique of tracing the thought process – that words emerge from deepening your thinking.

Takasaki: The subtitle of The Art of Words is "It's not something you come up with. It's something you think through." I resonate with that intensely. The backbone of skill in this work is whether you can maintain objectivity. No matter which route you climb or what expressive means you use, that's actually everything. Only true geniuses are allowed to create 100% subjectively.

There are techniques only the creator can write

Takasaki: After years of lecturing in various settings, there are moments when someone gives you that "Ah, I get it!" look. That feeling where "the moment someone understands, I understand so many things myself." I sometimes feel this during presentations too—that sense of connection instantly deepens my own thinking. My book is essentially me organizing those moments where I felt that connection, then giving myself the task of weaving them into a coherent narrative. So nothing in this book was forced or contrived.

Takasaki: After years of lecturing in various settings, there are moments when someone gives you that "Ah, I get it!" look. That feeling where "the moment someone understands, I understand so many things myself." I sometimes feel this during presentations too—that sense of connection instantly deepens my own thinking. My book is essentially me organizing those moments where I felt that connection, then giving myself the task of weaving them into a coherent narrative. So nothing in this book was forced or contrived.

Higuchi: I agree. I conduct training sessions in corporate divisions, and that's been a learning experience for me. For example, product planning know-how isn't very well established. Brainstorming sessions often happen without clear direction, with everyone just diverging randomly. Divergence is necessary, but it's dangerous to lack a methodology for "deepening" rather than just "flying off." How do you provide direction and generate meaningful ideas? My experience teaching that forms the basis of The Art of Ideation.

Isoshima: Training and lectures are tough, but it's worth taking them on. Recently, I was asked to teach creative writing within the company, focusing on how to write long pieces. You have to prepare yourself, right? That's great learning. When you see how just a little advice can dramatically improve things, it really solidifies your own confidence.

Takasaki: Long ago, while writing a lengthy piece for work, copywriter Koichi Ito told me, "Takasaki's writing is hard to read. Try randomly inserting words here and there." That moment was a revelation. Arranging words creates a need for rhythm in writing. You can use that rhythm to draw people in. I still struggle with it constantly, but I'm always conscious of it. Since then, "rhythm" has become a crucial measure in my work. The same goes for video editing. The same for layouts that grab people's eyes. Books you flip through. The structure of a two-hour movie. I feel like it became a major weapon once I realized that. There were actually quite a few seniors around me who would suddenly give me revelations like that.

Higuchi: Back in the day, we had some pretty reckless seniors, right? Like, "Show me what you're writing now. Hmm, totally useless" (laughs). I think that kind of "roughness" only comes from having a technical background backed by real experience. Maybe when the "rough" people disappear, the skills don't get passed down as easily as you'd think.

Higuchi: Back in the day, we had some pretty reckless seniors, right? Like, "Show me what you're writing now. Hmm, totally useless" (laughs). I think that kind of "roughness" only comes from having a technical background backed by real experience. Maybe when the "rough" people disappear, the skills don't get passed down as easily as you'd think.

Takasaki: I feel like I've written about those revelations from seniors in my book, within the limits of what I can articulate now.

(Continued in Part 2)

Takasaki:

Takasaki: Higuchi:

Higuchi: