The importance of thinking is understood. But where should one begin to deepen their "thinking skills" within daily work and life? For those struggling with how to take that first step, the three reflect on their own experiences and offer advice.

Raise the bar for yourself and hone your thinking skills

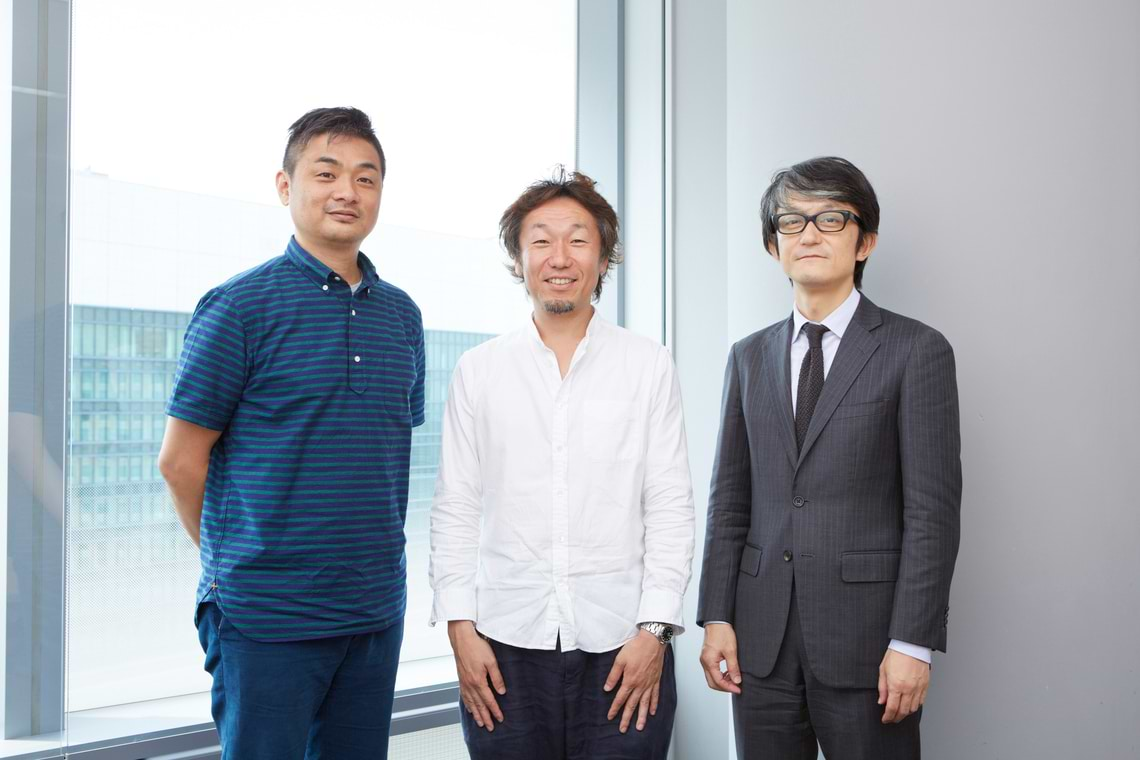

Takasaki: In this series, all three of us have emphasized the importance of "thinking skills." But how exactly should young people go about acquiring them?

Higuchi: First, it's crucial to constantly keep the bar high for yourself. If you think, "Well, this is good enough," you won't grow. In the past, demanding seniors or societal expectations raised that bar for you, but now you have to set it yourself. Visualizing the client and thinking, "For this person, I must go beyond this point," is one approach. Another challenge is how much you can handle doing every kind of work simultaneously. People often think quality drops when things get busy, but it's the opposite. When different aspects of each job influence each other, you start to see universal, important elements, and that actually helps maintain the quality of each task.

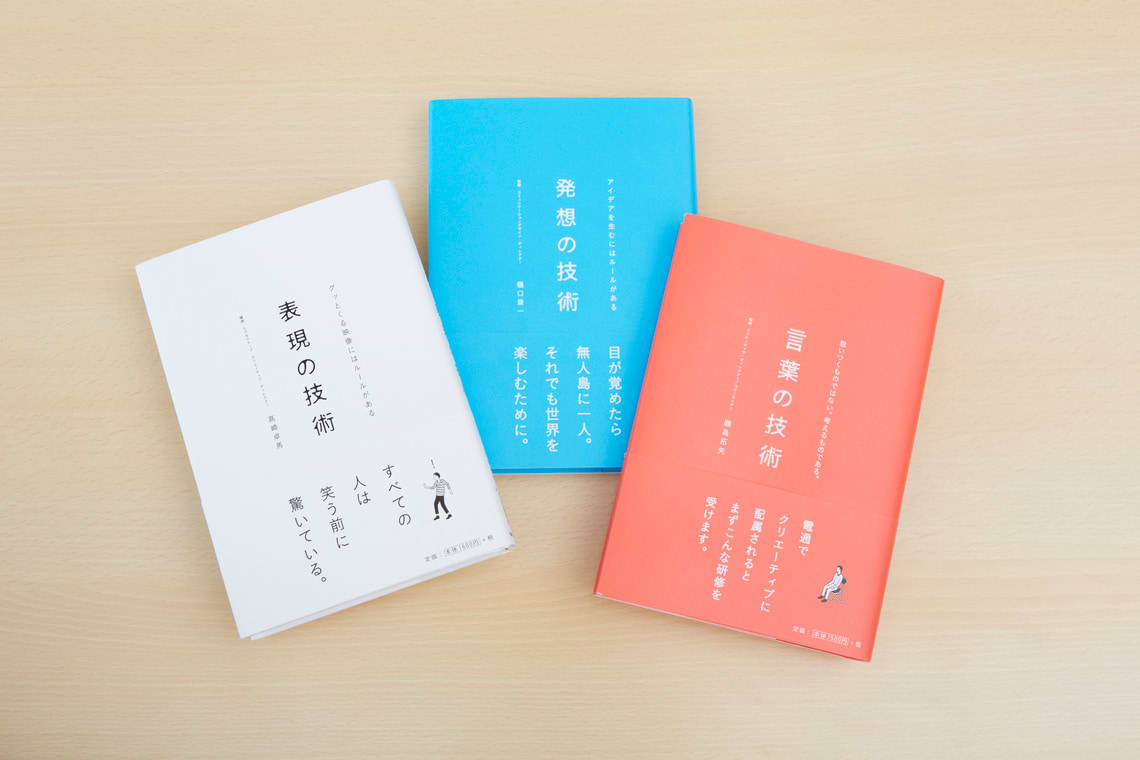

Isoshima: In 'The Art of Words,' I introduced thinking through four doors. I especially want younger people to be conscious of one of them: the 'Era/Society' door. Thinking about your own unique expression is natural and necessary, but it's easy to get stuck in a narrow place. How do you feel about the current society and people's moods? What would you show them to make them happy? It's good to think about this with a balanced perspective.

Isoshima: In 'The Art of Words,' I introduced thinking through four doors. I especially want younger people to be conscious of one of them: the 'Era/Society' door. Thinking about your own unique expression is natural and necessary, but it's easy to get stuck in a narrow place. How do you feel about the current society and people's moods? What would you show them to make them happy? It's good to think about this with a balanced perspective.

Higuchi: I think communication is about how much meaning you can project into the world. For it to succeed, there must be elements that many people can share. When using SNS, it's easy to think your immediate circle is the whole world, so perhaps we should always consider the opposite perspective.

Takasaki: Within a team, it's also crucial to be aware of how you function as an individual and where your responsibilities lie. When a sacrifice fly is hit to the outfield, everyone chasing the same ball is inefficient and pointless. A pro recognizes the strength of the fielder's arm and thinks about where they should relay the ball to prevent a run. You assign yourself responsibility, ensure others recognize it, and deliver results to earn their expectations. I believe work circulates like that. You must first establish self-awareness about where you create your value as a pro and how you hone it. Those are the people you get excited about working with.

Higuchi: To shoulder responsibility amid daily changes, you have no choice but to constantly update your necessary skills. It's a cycle, right?

Takasaki: After a presentation, a client who'd read my book 'The Art of Expression' once asked me, "Where's the surprise?" (laughs). Writing the book raised the bar for myself.

What kind of "muscle training" do you do daily?

Takasaki: Do either of you have any "muscle training" routines you keep up to hone your skills?

Takasaki: Do either of you have any "muscle training" routines you keep up to hone your skills?

Isoshima: Watching movies and reading all kinds of writing, I guess... Films are made with such dedication, you know. Just watching them is valuable, but analyzing why a film succeeds or fails—whether it's a hit or a flop—is incredibly educational. Everyone pours their heart into it, yet sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn't. Studying why by comparing the work itself, director interviews, critiques, and your own accumulated experience is how you learn. It's not just about expression; you also discover box office insights like, "Oh, this is what makes a hit."

Takasaki: So it's about grasping the gap between what society accepts and your own sensibilities?

Isoshima: Exactly. It's about thinking about various things efficiently, you could say.

Higuchi: I've been reading 20 books a month for decades now. I buy them just by looking at the cover. Thinking about the essence behind something that instantly catches your eye connects to advertising work. Even if I'm not interested in the content, it's good to have lots of platforms for thinking. Also, since I come from a marketing background, I look at survey data very meticulously. By continuing this, you can notice special changes happening within new data.

Takasaki: I do quite a lot of things. I record three days' worth of every TV channel. I want to feel the waves of popularity around actors and talents on my own skin. I want to cast them with conviction, and it's crucial to know for myself how things will look when done. It's also about responsibility. Plus, I've been running this "Advertising Police" thing for a long time (laughs). The moment I see a train ad hanging in the car, I instantly think about what's wrong with it, speculate on the cause, simulate the work process, and then just fix it myself. Then I consider how much impact that revised version might have on the world. I play this kind of mental game at high speed. I find it so much fun it's practically a hobby. My juniors who travel with me usually get a little freaked out.

Isoshima: Yeah, they probably do (laugh).

Higuchi: When I was a new employee, a senior colleague took me out to dinner every night for a whole year. The first week was tonkatsu every night, rotating through five carefully selected shops. Eating the same thing repeatedly made me appreciate each one's unique strengths. Then the next week was five gyoza spots, followed by five yakiniku places. That's when I started seeing the category's strengths too. The differences between individual shops and the differences between categories. "So this is what marketing is," I learned firsthand that year.

Higuchi: When I was a new employee, a senior colleague took me out to dinner every night for a whole year. The first week was tonkatsu every night, rotating through five carefully selected shops. Eating the same thing repeatedly made me appreciate each one's unique strengths. Then the next week was five gyoza spots, followed by five yakiniku places. That's when I started seeing the category's strengths too. The differences between individual shops and the differences between categories. "So this is what marketing is," I learned firsthand that year.

Takasaki: That's incredible. That senior intentionally designed it that way to help you understand, right?

Higuchi: Yes. I just remembered now—that was like "muscle training."

Takasaki: That's fascinating. It's great to have lots of unique people like that around.

Isoshima: But five days straight of tonkatsu is brutal (laughs).

Takasaki: It is tough (laughs). We heard many fascinating stories today. Thank you very much.

Isoshima &Higuchi: Thank you.

(End)

Isoshima:

Isoshima: Takasaki:

Takasaki: