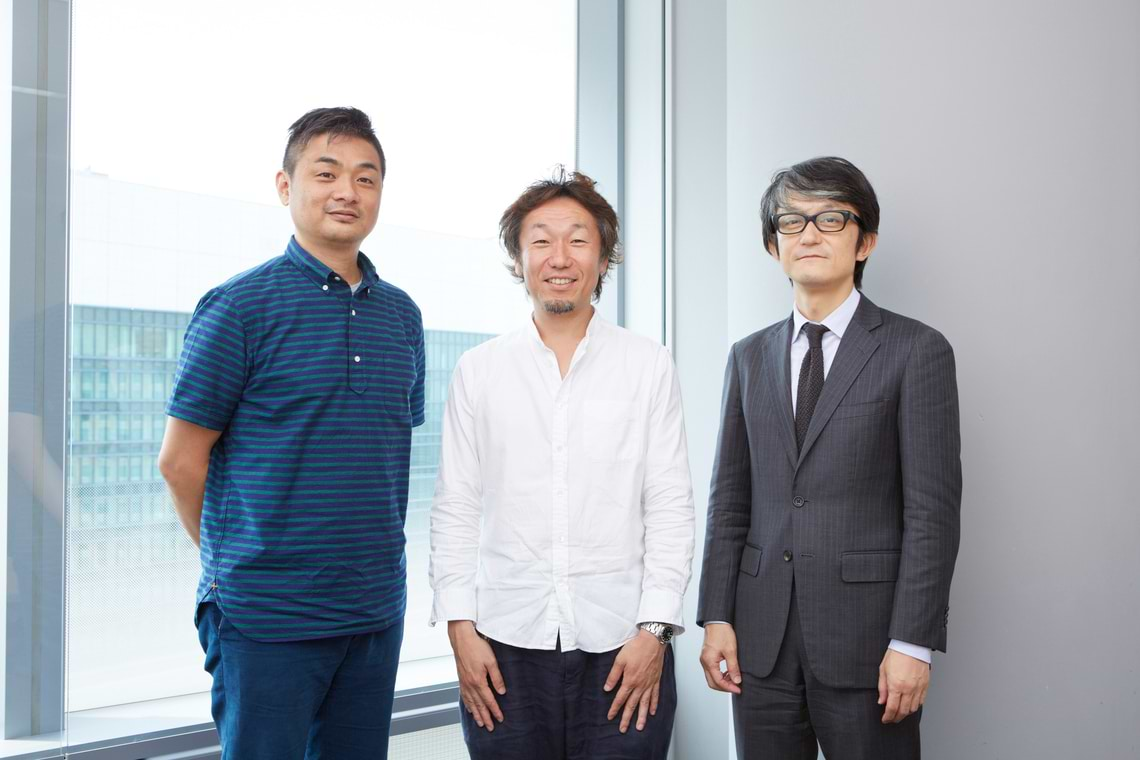

The changing media landscape continues to profoundly impact the creative world. How should young creators navigate this wilderness where "anything goes"? The three emphasize the importance of "words" at the core of "thinking techniques."

Words lie at the heart of every project

Isoshima: Today's young creators are standing in the wilderness, so to speak. It must be incredibly tough. Even the old adage, "First hone your skills as a copywriter," seems uncertain now. I myself was raised with the principle of "words first," so even with various wilds to navigate, I have a "foothold" to move forward.

Takasaki: In the past, there was ample time to hone skills within the "box" of creativity, allowing one to recognize their strengths, weaknesses, and nature. But today's people have no time to even confirm where their backbone lies; they must walk through a wilderness where "anything goes." Freedom is actually a form of constraint. While there's potential for suddenly mutating into incredibly interesting talent, it might require tremendous vitality.

Isoshima: I heard from a new hire, "For the first six months after joining, I've been making apps nonstop." What kind of "muscle" does suddenly making apps build? It's impossible to explain based on past experience alone these days.

Higuchi: However, I believe words lie at the heart of every project. I feel uneasy when those words seem weak and ambiguous. If we use loose language to describe the means—"Let's go with this concept, this kind of video, this kind of website"—I doubt it will translate into something that truly resonates with the world. Regardless of whether you're a copywriter or not, the skill everyone in the advertising industry must hone is the craft of words.

Higuchi: However, I believe words lie at the heart of every project. I feel uneasy when those words seem weak and ambiguous. If we use loose language to describe the means—"Let's go with this concept, this kind of video, this kind of website"—I doubt it will translate into something that truly resonates with the world. Regardless of whether you're a copywriter or not, the skill everyone in the advertising industry must hone is the craft of words.

Takasaki: Even if you make an incredible invention, if you don't create words that convey it, no one will discover it.

Higuchi: I also sense this strange misconception that "good words are clever words." Being accurate is more important than being clever. Isn't this happening in many fields, not just copywriting?

Takasaki: Learning copywriting is incredibly close to learning the language of communication. Whether you can see that or not makes a huge difference.

Higuchi: Talking with top executives and business unit heads makes you realize that words are central to everything—business strategy, operational strategy, and product planning. Concise words that unite tens of thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of employees and stakeholders toward a single direction. Top executives understand that this demands a power of language nearly equivalent to copywriting. Our work extends beyond advertising communication into the realm of how to elevate a client's business through ideas. Shouldn't we train to strengthen the language in this area?

"Intensity of Plea" and "Meta-Frame"

Isoshima: That's a different concept from copywriting in the narrow sense, right? In Uchida Tatsuru's book 'Street-Level Stylistics' (Mishima Publishing), he introduces the term "intensity of appeal." He argues that only the intensity of that appeal – the sheer force of wanting the reader to listen, to understand – determines the quality of the writing. Indeed, if you can find something with that intensity of appeal, it becomes good copy as is. I think that's probably close to what Higuchi-kun is saying?

Higuchi: It is similar.

Takasaki: It's not about mental attitude.

Takasaki: It's not about mental attitude.

Isoshima: Thinking "If I do this much for this assignment, I'll probably get 85 points" will never improve quality. Even if the word count or theme is fixed, you have to find the "intensity of appeal" within that framework – what you truly want to convey.

Takasaki: For everyone, discovering that "something that makes you want to create it so badly you can't stand it"

is the starting point for all expression, so it's absolutely essential.

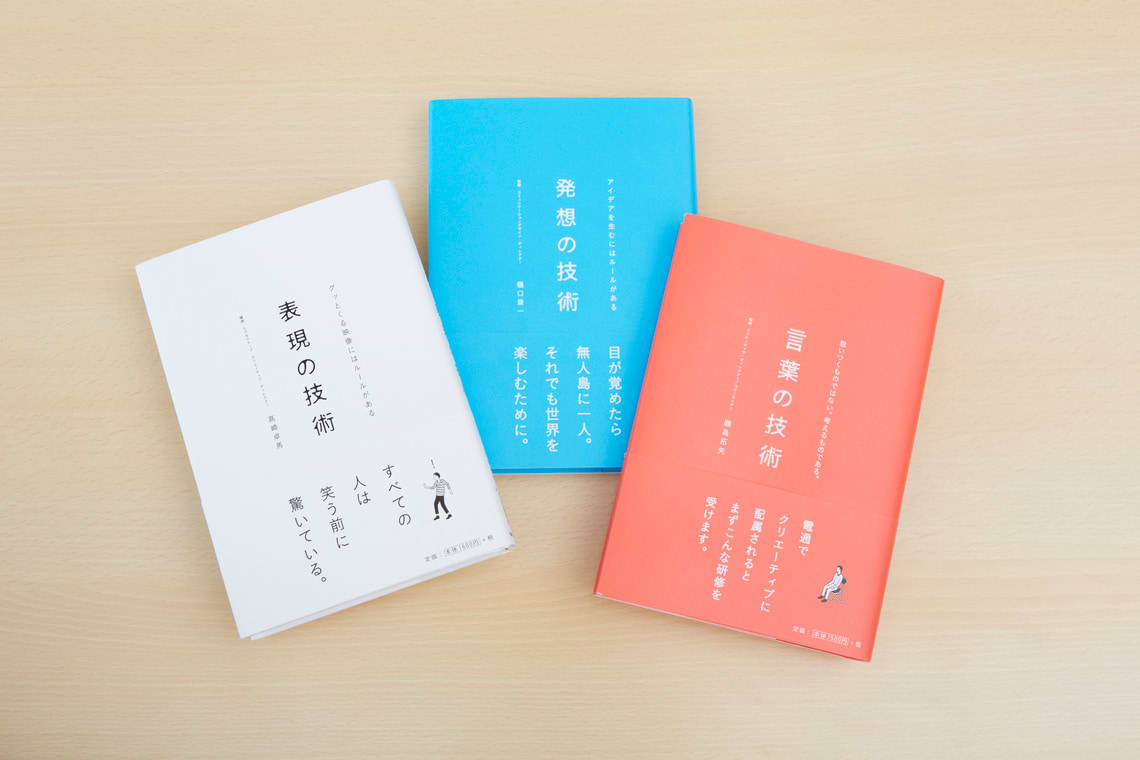

Higuchi: People might say what we're talking about isn't technique, it's just mental attitude. But isn't that exactly what the three books in the Technique series are saying? That technique includes the intensity of feeling, that conviction that "This is what needs to be communicated right now!"?

Takasaki: Exactly. The weather on the mountain called advertising is fundamentally unpredictable. It keeps changing. Having 50,000 manuals doesn't guarantee you can adapt to those changes and reach the summit. You can't do it without the mental fortitude to question the past every time and seek new answers. I think that's what mountaineering technique is all about.

Isoshima: Occasionally, a "monster" like Masahiko Sato appears and shows us a completely different route.

Takasaki: There's something in Mr. Sato's expression that we can't put into words, something that would surely be lost if we tried to verbalize it too easily. Something you can't replicate even if you try. Even if you create something following Mr. Sato's rules, that particular quality won't emerge.

Isoshima: Uchida's book introduced the linguistic concept of "meta-frames." Like when a teacher asks, "Can the back row hear me?" and someone in the back yells, "Can't hear you!" It's incredibly contradictory, but there are definitely words that get through before meaning—those are the meta-frame words. I thought this feeling was close to Sato's "something that inevitably gets through."

Isoshima: Uchida's book introduced the linguistic concept of "meta-frames." Like when a teacher asks, "Can the back row hear me?" and someone in the back yells, "Can't hear you!" It's incredibly contradictory, but there are definitely words that get through before meaning—those are the meta-frame words. I thought this feeling was close to Sato's "something that inevitably gets through."

Takasaki: That's fascinating. Something that inevitably gets conveyed. I hadn't consciously thought about it, but it feels like something I've always been aware of. Even when communicating about products or companies, I feel like I'm constantly, consciously designing that part that gets conveyed before the actual message—putting a lot of effort into it.

Higuchi: How universal is meta-frame? It feels like it could transcend time, doesn't it?

Takasaki: It also feels close to the creator's personality. That part inevitably seeps through. When humans communicate with humans, that something that gets conveyed regardless. Maybe that's why we can still be moved by old movies and literature today.

(Continued in Part 2)

Higuchi:

Higuchi: Takasaki:

Takasaki: Isoshima:

Isoshima: