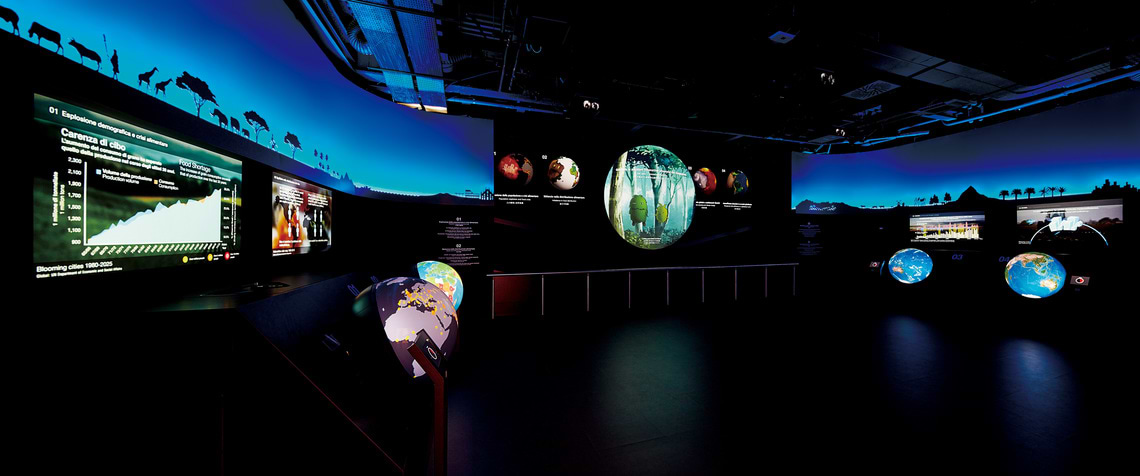

The Milan International Exposition (Expo Milano) ran from May 1st to October 31st. At Scene III "Innovation" in the Japan Pavilion, centered around Shinichi Takemura's "Touchable Earth" exhibit from Kyoto University of Art and Design, various global food and agriculture challenges were presented. Japan's unique solutions were expressed through compelling visuals (stories). Mr. Takemura, along with Mr. Ryoji Shimizu, who handled the planning and production of the robots, and Mr. Shinichiro Urahashi from Dentsu Inc. looked back and discussed the experience.

Reporting & Editing: Aki Kanahara, Dentsu Inc. Event & Space Design Bureau

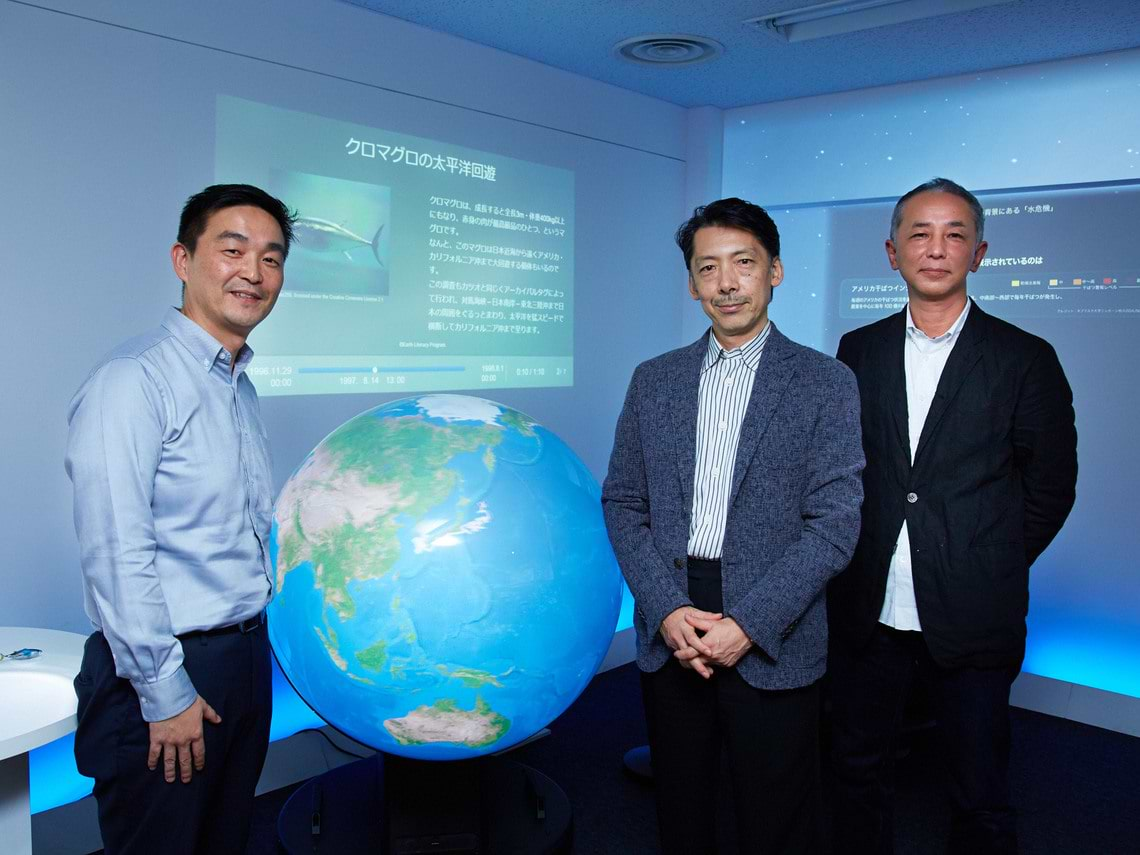

(From left) Shinichiro Urahashi, Shinichi Takemura, Ryoji Shimizu

Global raw material prices for food are rising

Urahashi: The Milan Expo is being held under the theme "Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life." Mr. Takemura, what are your thoughts on the global food challenges facing our planet?

Takemura: In Japan, the idea that food or agriculture is in crisis doesn't really resonate. Even when food prices rise, it's on the level of bread going up a few yen. That's because in developed countries like Japan, the proportion of raw material costs in the final product is relatively small. So even when raw material prices rise, the impact isn't that great, allowing us to remain somewhat oblivious. But globally, the prices of wheat, corn, and soybeans worldwide have already risen to three to four times their 20th-century levels.

Fundamentally, while emerging economies like China grow wealthier and consumption increases, China itself faces water shortages due to Himalayan glacial melt from global warming – the Yellow River has effectively stopped flowing. The fact that the Yellow River, cradle of one of the four great ancient civilizations, no longer flows to its mouth is something most Japanese people are unaware of, yet this phenomenon has become pronounced since the mid-1990s. Consequently, the North China Plain, an agricultural region within the Yellow River basin, is becoming unsuitable for farming.

It was already remarkable that China could sustain 1.35 billion people through self-sufficiency. But if they start importing 10-20% of their food from abroad, that alone equals Japan's population. The Himalayas aren't just the water source for Asia's eastern rivers like the Yellow, Yangtze, and Mekong; they also feed Afghanistan to the west, where water scarcity is also growing.

While news headlines focus on refugee crises or wars, the root issues are water scarcity and food shortages. The China risk is more severe than economic bubble collapses, air pollution, or factory explosions. The critical question is how 1.35 billion people will feed themselves in the future. Agricultural scientists call this the "water bubble (collapse)," though it's not widely recognized.

Shimizu: That's truly terrifying.

Turning Japanese Technology into a "Peace Weapon"

Takemura: The Milan Expo, addressing the challenge of "Feeding the Planet" for a projected 9 billion people by 2050, is about confronting this global vulnerability head-on. Globally, 800 million people currently suffer from undernourishment, while developed nations have 2 billion obese citizens. Both represent significant global food challenges, both quantitatively and qualitatively. The Milan Expo called on the world to properly address these issues. Among the world pavilions, I believe Japan's pavilion effectively presented solutions to these challenges.

Urahashi: For example, the UAE in the Middle East centered its narrative around water. The messages different countries convey inevitably reflect their national circumstances. What are your thoughts on Japan's unique problem-posing and solutions that can contribute to the planet?

Takemura: We presented a total of 16 solutions. I can't explain them all, but to give one clear example: the increase in meat consumption is further straining the already precarious global food supply. As economies grow worldwide, meat consumption rises. China's meat consumption has increased about tenfold in just the last few years.

When agriculture becomes unsustainable while meat consumption rises, corn that previously fed ten people becomes feed for cattle. Using it that way reduces its value to one-tenth—enough for just one person. So meat consumption is a very luxurious diet. While it wasn't a problem when grains were abundant, as global food supply and demand tighten, the increase in meat consumption becomes a major stressor on the food problem.

In contrast, Japan, with Buddhism introduced during the Asuka and Nara periods prohibiting meat consumption, developed high-protein, nutrient-rich dishes without meat in temples and monasteries. This led to the advancement of soy-based foods like yuba and tofu. Now, with further advanced technology like the USS process (a technique separating soy components into cream and low-fat fractions, similar to milk), methods for eating soy deliciously and efficiently have been developed. I even think this could become the standard for the 21st century.

Urahashi: Interest in Japanese cuisine will only continue to grow from here on out.

Takemura: Lately, factors like unpredictable weather, abnormal climate events, and climate change are causing poor harvests in agriculture. However, Japan is experimenting with growing crops in urban spaces, like vacant buildings, using plant factories and other methods. This innovation of "agriculture within cities" is already underway. The technology for fully farmed tuna is also remarkable. Endangered species like tuna and eel can be raised entirely from eggs in controlled environments. This spares natural resources from stress, and even as ocean acidification worsens due to rising CO2 levels, threatening the seas, fish can still be successfully cultivated artificially.

I believe such Japanese technology is a "peace weapon." In other words, dealing with refugees after they emerge, or conducting airstrikes after conflicts erupt—these are all symptomatic treatments. It's like deciding how to perform surgery only after someone gets sick. I think a "peace weapon" is providing solutions beforehand to prevent the illness from occurring in the first place. If Japan claims to pursue "proactive pacifism," then Japan has many such peace weapons. I want to send the message: "Please make use of them."

Japanese cuisine is the food of the future

Urahashi: Mr. Shimizu, within this project, were there any solutions that particularly caught your attention? Or did you personally rediscover something about Japan?

Shimizu: Hearing Professor Takemura speak revealed many things I hadn't known before. Being immersed in the grand theme that "Japanese cuisine is the food of the future" was truly rewarding. It made me realize that what we express carries such a significant theme. While I participated as a video creator, I felt strongly that, beyond just that perspective, as a Japanese person involved in the Expo, I absolutely must find a way to concretely express how "Japanese cuisine can be the food of the future."

Takemura: Thank you. To add, regarding obesity issues, research shows that meals containing umami—the flavor we take for granted in dashi, derived from ingredients like kombu and bonito flakes—are low in fat, sugar, and salt. They provide satisfaction to the brain and help curb overeating.

On the other hand, ingredients like cheese and tomatoes from around the world also contain glutamic acid. It's just that the concept of "umami" didn't exist globally before. I wanted to clearly convey that Japan's food OS, centered on umami, is packed with secrets and techniques for promoting global health.

Furthermore, Japan's fermentation techniques are magical. Take takuan pickles: they can increase the vitamins and minerals naturally present in daikon radish by over tenfold. Natto, compared to just boiled soybeans, has vitamins and minerals multiplied many times over. There's incredible know-how behind the ingredients we eat daily without thinking. Moreover, as a technology enabling long-term preservation, it can make a huge contribution to the world.