The Milan International Exposition (Expo Milano) ran from May 1st to October 31st.

At Scene III 'Innovation' in the Japan Pavilion, centered around Shinichi Takemura of Kyoto University of Art and Design's 'Touchable Earth' exhibit, various global food and agriculture challenges were presented. Japan's unique solutions were expressed through compelling visuals (stories). Takemura, along with Ryōji Shimizu, who handled the planning and production of the robots, and Shinichirō Urahashi of Dentsu Inc. looked back and discussed the experience.

Reporting & Editing: Aki Kanahara, Dentsu Inc. Event & Space Design Bureau

(From left) Shinichiro Urahashi, Shinichi Takemura, Ryoji Shimizu

How to express diverse global challenges and solutions through exhibition design

Urahashi: As a venue for sharing global challenges, could you tell us about any particular approaches you took with the exhibition?

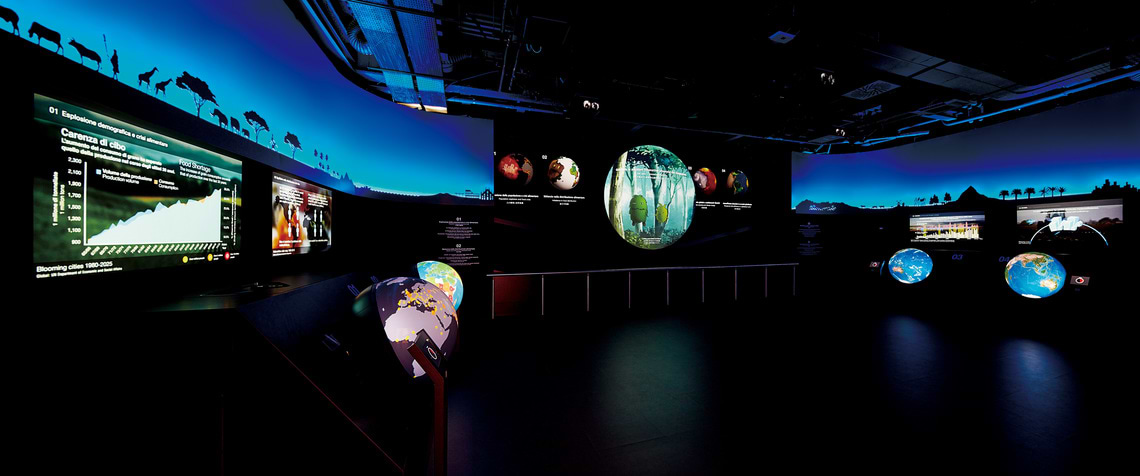

Shimizu: Having been involved in the work for the Japan Pavilion at Expo Milano and understanding the overall flow, I was constantly conscious of how the exhibition for Scene III "Innovation," which I was responsible for, was positioned within the whole. Within the pavilion's flow, the section preceding this exhibit introduced Japanese food from a relatively micro perspective, delving into details like fermentation and ingredient characteristics. The section following this exhibit moves towards a more entertainment-focused flow, placing our exhibit squarely in the middle. I thought it would be impactful if visitors could experience the expansive scope of the theme from a global, bird's-eye perspective at this point.

Japanese cuisine is a culinary culture that delves into the minutest details and possesses a delicate nature. However, I wanted visitors from around the world attending the Expo to take home the image that, by shifting perspective, it could potentially become a global solution. To maximize the impact of Professor Takemura's digital globe, "Touchable Earth," I decided to place the Earth as the central theme for the main screen content as well, aiming to create a memorable fusion of these concepts.

※Video footage provided by: Earth Industry and Culture Research Institute, General Incorporated Foundation / JA Group

Takemura: In your scenario, Shimizu-san, you used characters like Morizo and Kikkoru to convey humanity's message. The entity making the appeal wasn't human.

Urahashi: A third-party presence.

Takemura: Yes, that felt like a distinctly Japanese expression. Not a Christian concept, but rather embodying the Japanese sensibility that all things possess souls, carry messages, and hold potential Buddha-nature—though not quite the same as "all beings attain Buddhahood" (sansen sōmoku shikkai jōbutsu). Morizo and Kikkoru represent a modern expression of that feeling.

Also, coming from the previous exhibition, there was this sudden, dramatic expansion—both temporally and spatially. Our intention was for visitors to experience that sudden widening of perspective, to truly share in the human challenges and their solutions before leaving.

Urahashi: Mr. Shimizu, you worked on several types of animation expressions. Could you share your thoughts on that?

Shimizu: The central pillar was the globe-shaped screen, and we structured the exhibition to add depth with animation. As is common in European countries, Italy in particular has a deep affinity for Japanese animation. We envisioned using animated characters as storytellers positioned around the globe screen to capture everyone's eyes and hearts.

What emerges from the blending and clashing of cultures

Takemura: I think it was a uniquely Japanese characteristic that the entity calling out, "Let's think about the Earth like this," wasn't human. We often talk about stewardship – that humans must protect the Earth and nature or face dire consequences. But here, the entities delivering the message are all non-human things: creatures you can't tell if they're animals or plants, robots, and so on. They say humans have collaborated with nature to build the Earth, yet humans themselves don't particularly appear.

Shimizu: I'm really glad you see it that way. Japanese culture is also about blending various cultures, so with the robot and stork story, we deliberately tried to create that sense of incongruity. I hope it shows that when things that normally don't mix collide, what emerges and the results can unexpectedly offer a much broader perspective.

Urahashi: Now that the exhibition is complete, what are your thoughts on its achievements and significance?

Shimizu: Working alongside Professor Takemura was an incredibly valuable learning experience. The final output of this project's content was an encounter that will undoubtedly influence my own creative work going forward. Professor Takemura's ideas are deeply embedded in the animation's story—in fact, they form its very pillars. Japan isn't a country formed by chance. It was shaped alongside this land by the creativity of its people. While I vaguely understood this intellectually, it didn't truly resonate until I heard Professor Takemura speak.

Terraced rice fields don't just appear on their own; Japan has a history of creating them. Seeing the Japanese landscape now, feeling the people who built them, the agriculture, the food culture, changes everything. My perspective has definitely shifted. I'm truly grateful to have been involved in this work and to have met Professor Takemura.

We must share the achievements of the Milan Expo with Japan's children

Takemura: We can't let it end here. Today's Japanese elementary, middle, and high school students likely have almost no opportunity to learn about it. I believe the content we expressed at the Milan Expo is an achievement that must be properly shared with Japanese children. For example, I want this to be the starting point for activities, working with the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries and JA, to communicate this theme domestically as well. What matters is what comes next.

Urahashi: As Mr. Shimizu mentioned, Mr. Takemura's talk was about rediscovering Japan. It made us realize how much we take for granted, overlaid with perspectives built up over a very long history.

Takemura: To add to that, it's not just about heritage; it's about how people creatively engage and maintain it continuously—cleaning waterways, maintaining rice fields. This is done by local communities, including cooperatives. We can import rice, but we can't import land or local communities. We mustn't forget that it's not just about having a past history; it's the ongoing activities of living people today that make it possible. The spotlight tends to fall only on cutting-edge technology and ventures.

Urahashi: That's right. The entire culture, including food production, should be creative.

Takemura: Actually, there are tons of cool farmers out there. If Expo Milano was the catalyst for rediscovering that this is a field worthy of respect, then I think it would be great to start focusing more on the untapped resources in the food and agriculture sector that haven't yet received the spotlight.

The Earth faces many problems. We can visualize them on a globe, but just as many solutions are emerging. Talking about global environmental issues tends to make everyone gloomy, but there's also plenty of bright news that can break through that. For example, Mr. Shimizu animated why the agricultural revolution happened – how worsening climate led to food crises, yet people still worked hard to cultivate wheat that grew bravely in such harsh conditions. Sometimes, constraints actually spur creativity.

The urban revolution was similar. As the land dried up, people had no choice but to gather and live around rivers, leading to the formation of large cities along waterways. Times labeled as crises are also opportunities within that field. I want to convey this message more strongly to the younger generation.

Shimizu: I actually think people in Europe and America might have more expectations or insights about Japanese food than we do. If many people in Japan are still going about their lives without realizing this, it feels like a tremendous waste.

Takemura: There's this image that preparing one soup and three dishes is a lot of work, right? When a master of Japanese cuisine comes along and demonstrates how to make dashi like this, it has its pros and cons. But I think the true beauty of Japanese food lies in the fact that you can just plop kombu and bonito flakes into boiling water, and in less than five minutes, you have the best dashi. We should be communicating that you can easily and simply create the highest quality slow food – "fast slow food."

Shimizu: That's absolutely right.

Takemura: It's wonderful that masters of Japanese cuisine influence chefs in France and Italy, but we also need to shine a light on how effortlessly you can make Japanese food – as easily as toasting bread or brewing coffee.

Urahashi: The Japan Pavilion is promoting that aspect too.

Takemura: How about bringing the Japan Pavilion exhibition to Japan as it is?

Shimizu: That's a great idea!

Urahashi: Exactly. Actually, I feel like the people who should really see the Japan Pavilion are the Japanese themselves. It was great to have this relaxed time today with Professor Takemura and Shimizu-san, reflecting on the Milan Expo exhibition. We definitely want to share this initiative and its results with Japanese children and build on it for the next action.