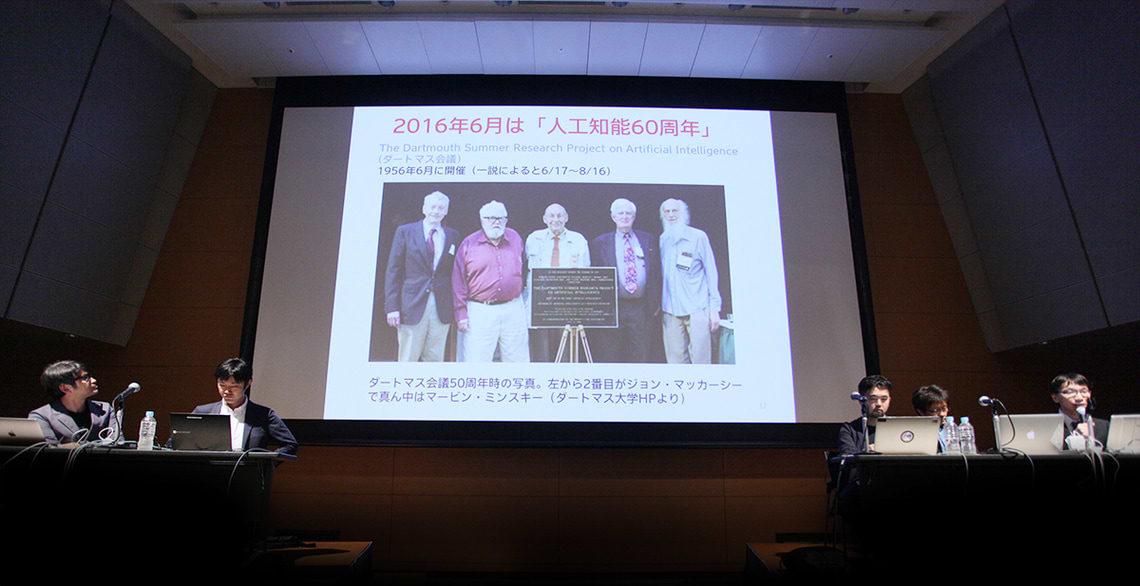

Some view artificial intelligence pessimistically as "something that will take away jobs humans do," but fundamentally, it should be used to expand the ways humans live. This Dentsu Inc. Design Talk explores the future brought by artificial intelligence. The speakers are Dr. Yoshiki Ishikawa, a medical doctor researching preventive medicine × AI; IT entrepreneur Dominic Chen, also a leading figure in information science research; creator Tetsuya Mizuguchi, who constantly incorporates cutting-edge digital technology to create new forms of expression; and Hiroshi Yamakawa, Director of Dwango AI Research Institute. They discussed a future where AI is not just "artificial" but "intelligent" as a matter of course, focusing on creativity, desire, the mind, and emotions, viewing technological progress positively. The moderator is Fumi Hito, leader of Dentsu Inc.'s cross-functional internal organization specializing in AI. Following the first part, we present the second part.

(From left) Mr. Mizuguchi, Mr. Ishikawa, Mr. Dominique, Mr. Yamakawa, Mr. Nitta

Understanding human desires well

we can glimpse the "happiness" AI brings.

Dominique: My wife loves cooking, but her job is so busy she rarely has time to cook herself. I've been wondering—if I gave her Chef Robot from the Ishikawa team, would she actually be happy? I suppose the freedom from labor might seem like a benefit, but I think she'd insist on wanting to handle the creative process herself. (※ When I asked her later, sure enough, she snapped, "Don't take away my healing time of cooking!" (laughs))

Mizuguchi: There's always debate about what truly makes us happy. Take a super-rich person who could eat whatever they wanted every day—would that really make them happy? Maybe not. If you break down the desire to "eat delicious food," it might not just be about eating delicious food.

Dominique: Reading various AI research books, one point that really doesn't sit right with me is the lack of insight into how human desires are designed. Take fermented foods, for example. They're foods where fermentation and decay are two sides of the same coin. You could even say they're potentially dangerous foods. But I think people derive pleasure precisely because they take that risk.

Mizuguchi: Probably, what makes a chef robot enjoyable isn't just how well it cooks. For instance, if a robot teaches you various cooking tips and supports you by saying, "You can do this too," that kind of robot could make people happy.

Dominique: Exactly. When we asked people involved in making fermented foods, "What kind of information technology do you want?" they all said the same thing. It seems "happy" that technology subtly supports human learning, keeping humans as the main actors, thereby increasing the number of skilled cooks and connoisseurs.

Nitta: When developing AI chatbots, it's conceivable that humans might develop strong emotions toward them, regardless of whether the AI itself possesses feelings. It's somewhat akin to becoming overly engrossed in dating simulation games. How do you view such issues?

Mizuguchi: Like the world depicted in the movie "Blade Runner," where it becomes impossible to distinguish between replicants and humans, the future of AI is often viewed pessimistically. But the actual future might not be like that. While the pattern of AI making people happier or more prosperous hasn't been fully explored yet, I believe a positive version of "Blade Runner" is possible.

Ishikawa: In emotion research, we use birds called Whiteheads. When comparing learning from a real master bird versus listening to a recorded voice, even though the information is the same, learning from the live bird is more effective. Something gets lost the moment it's digitized. This is said to be a hint for thinking about emotions.

Yamakawa: In experiments where robots play games with children at daycare centers, the level of engagement differs significantly depending on whether the robot is operated by an amateur or a childcare worker. Childcare workers can likely adjust the difficulty of problems finely while observing the children's reactions.

Mizuguchi: Listening to everyone, I started thinking that developing games, VR, and AI might be like quantizing and reconstructing something deeply human. Looking back from the future, perhaps the internet will be seen as having quantized things.

Is AI with a mind possible?

The Relationship Between "Emotion" and "Mind"

Nitta: Let's delve a bit deeper into the realm of the "mind." This diagram (below) positions artificial intelligence within four quadrants. The vertical axis maps "strong AI" possessing a mind or consciousness versus "weak AI" lacking it, while the horizontal axis distinguishes between "specialized" and "general-purpose" AI. It's said that currently, only "weak specialized" AI exists—without a mind and with a clearly defined purpose. But are researchers at DeepMind and proponents of the Singularity aiming for "strong general-purpose" AI that possesses a mind and can discover its own purpose? And can the presence or absence of a mind even be quantified? ...Fundamentally, is it even possible to have AI that has a mind but is specialized, or that lacks a mind but is general-purpose?

Yamakawa: Historically, we started with specialized AI. For example, an AI developed for Go can only play Go, whereas a professional Go player possesses general intelligence—they can play Go, but also shop or clean. In the past, humans had to create specialized systems, but today's AI can learn independently. Given data, it can acquire knowledge across various fields.

For an AI system to achieve true general-purpose capability, it needs to enhance its ability to make analogies—like humans observing birds to create airplanes—by drawing knowledge from other domains. On the other hand, research into the "strong AI" aspect, as Mr. Nitta pointed out, remains relatively limited. The term "strong AI" relates to "mind or consciousness," but such concepts are difficult to set as research goals. Rather than thinking along the difficult axis of mind or consciousness, I believe it's more realistic to consider the axis of emotion. Even without a mind, we can create interfaces that express emotions capable of human-like empathy, making the AI appear human-like.

Hito: So, even if we don't know whether AI possesses a mind, we can stage behaviors that make it appear as if it has one, giving the illusion of consciousness or a mind.

Considering the Relationship Between AI "Creation and Imitation" and "Copyright"

Nittō: Next, I'd like to ask about "Creation and Imitation." For example, when you feed text to an AI and have it automatically generate content based on certain rules, sometimes it produces interesting results that surpass the original. What happens to copyright in such cases?

Dominique: I think the very idea of attributing creativity to an individual is fundamentally a very Western "poverty." Japan and the East are more attuned to a collective intelligence mindset, and the custom of valuing anonymous culture is stronger in Japan than in America. However, since we live in a global economic society, we must give something back to society. The Creative Commons concept is about continuing the actions of the original creator regarding open content placed online. This isn't special; it's been done since long before the internet. But the internet made it faster and cheaper. AI might help us visualize the vast amount of information and human activity behind our seemingly trivial words or gestures, potentially linking this insight to a new economy.

In his book "The Smooth World and Its Enemies," Ken Suzuki proposed the virtual currency "PICSY." For example, I treat Ishikawa to ramen. This energizes Ishikawa, enabling him to write an excellent paper. It gets published as a book, earning him 100 million yen. Yet under the current monetary system, I don't get a single yen. Ishikawa might treat me to ramen in return, but that's it. Technologies like Git for software and blockchain for digital currency handle creation processes and transaction histories. If we could more easily handle the histories of all phenomena, we might develop systematic ways to reduce invisible inheritance relationships. Laws and cultures would likely adapt to such technologies.

Mizuguchi: Hearing that made me wonder: What if we quantified the mechanisms of companies and organizations? Right now, HR evaluates compensation for work. But if daily tasks could be broken down, with time spent and contributions quantified for assessment, managers would likely become unnecessary. When you engage creatively with various people, compensation reflecting that activity would be automatically deposited into your account. I think that's the direction we're heading. A "quantum democracy" concept will definitely emerge.

Ishikawa: Right now, I'm researching business card exchanges using a database with a company called SanSan, which does cloud-based business card management. I started thinking that exchanging business cards is essentially exchanging ideas. By using this database, I thought we could understand how quickly ideas are flowing through Japanese society right now and where I fit within that. When we actually analyzed it, we discovered something incredibly interesting. Using these results, you could figure out who among your acquaintances would be most interesting to meet right now, or who to connect with whom would be most beneficial. However, I'm writing a paper on this, and I'm wondering about the copyright implications. I don't know any company or personal names, and I've obtained permission from the companies involved, but there have been past cases where using data for research without proper authorization caused problems...

Dominique: Technologies for anonymizing big data are emerging, and there are techniques for synthesizing samples too. The environment is becoming more conducive to moving forward without excessive concern over rights. Still, seeing people like Ishikawa and Yamakawa, I feel research and society are becoming increasingly interconnected.

Yamakawa: Indeed, the rapid advancement of AI today is largely driven by the high-speed exchange of ideas facilitated by the internet. With various research reports frequently becoming openly available at an early stage, the cycle of "standing on the shoulders of giants" is accelerating.

We shouldn't treat AI discussions as a black box

Dominique: Whenever we discuss AI, the question "What if AI is misused?" inevitably comes up. What I always think is that we haven't yet developed the right mindset for these conversations. Preconceptions like "this person is positive" or "this person is negative" get in the way, making it hard to have free-wheeling, constructive discussions and reach consensus.

What gives me hope about AI right now is that the people confronting AI technology on the front lines are engaging in ethical discussions about it. As the technology trickles down to civilian use and becomes less of a black box, these discussions should become more open. Rather than getting bogged down in value judgments about good and evil, we need to focus on creating an open environment where more people can scrutinize it and increase the probability of good ideas. I believe that's the best approach.

Yamakawa: There's no doubt that artificial intelligence will become deeply integrated into our lives. While the happiness of those living today is important, I also believe it's equally crucial to ask what we want to leave behind for the next generation. If we broaden our perspective and examine Earth's history, it's true that life has persisted, but looking at individual species, over 99% have gone extinct. Therefore, it's hard to imagine humanity persisting in its current form 500,000 years from now. Now that artificial intelligence has advanced significantly, we possess great power while also gaining deeper self-awareness. I feel we've entered an era where we must contemplate the future world—including how we will walk alongside artificial intelligence and what we will and will not entrust to it.

<End>

You can also read the interview here on AdTie!

Planning & Production: Aki Kanahara, Dentsu Inc. Event & Space Design Bureau