He also runs the school's flagship program, Venture Lab, where students work on startups aiming to secure funding from investors. I participated in this program myself.

Before becoming a professor, he worked in sports-related fields and collaborated with Dentsu Inc., so he knows Japan well.

After class, I caught up with him at a bar near campus.

Nami: Can entrepreneurship even be taught in school?

Paris: We don't teach "how to become an entrepreneur." Becoming an entrepreneur involves significant risk. Not everyone can do it, and we can't teach that.

What we teach is "thinking like an entrepreneur."

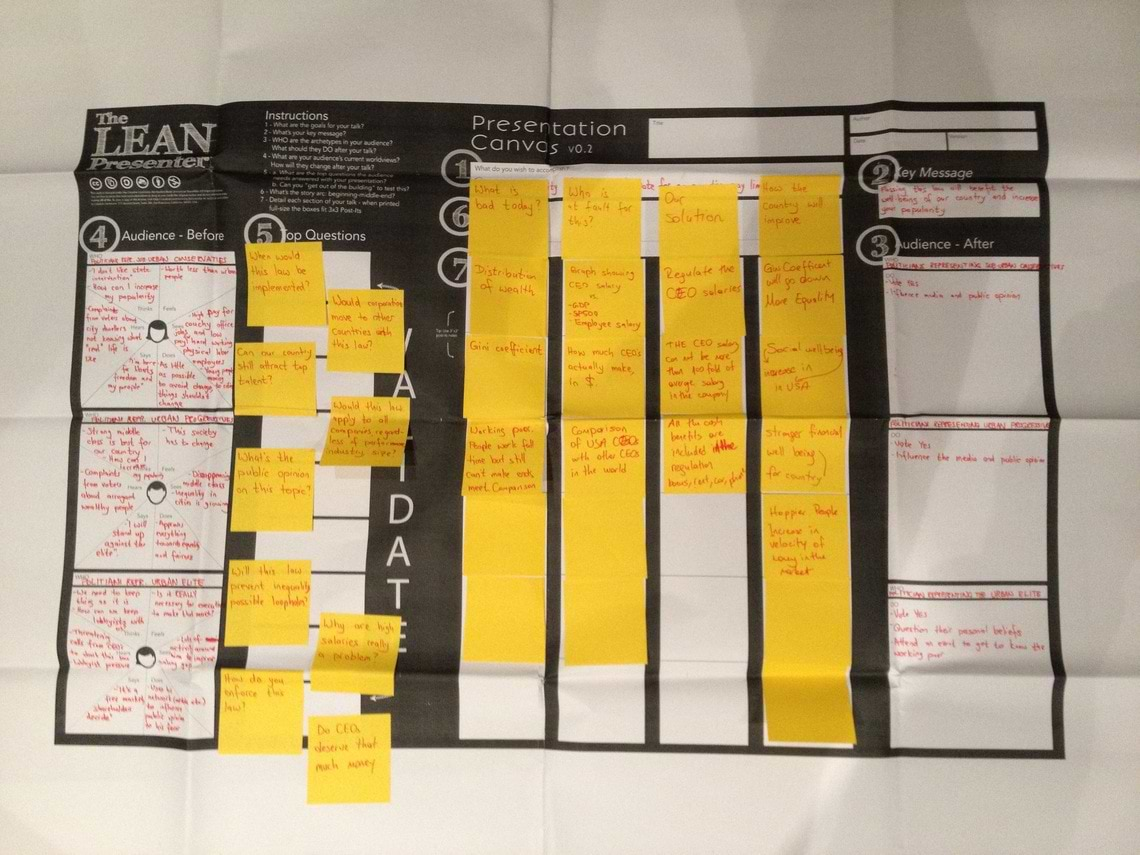

At Venture Lab, we spend four months teaching how to think to turn an idea into a business. The ultimate goal is to present to investors at Venture Day and secure funding. Our first Venture Day in Tokyo will be held on December 9th.

Nami: How do you view the relationship between "what you learn in lectures" and "real business"? Personally, I felt I gained more inspiration from Venture Lab and workshop-style elective courses (like consulting for startups or proposing M&A deals to companies) than from classroom lectures.

Paris: Real-world experience is crucial. Talking with clients is real business. That's why you must balance business and study.

Most people in the business world think, "University is unrelated to work; it's a different world." That's true. Therefore, we must integrate university into actual business. If we can't do that, it becomes "the MBA is useless."

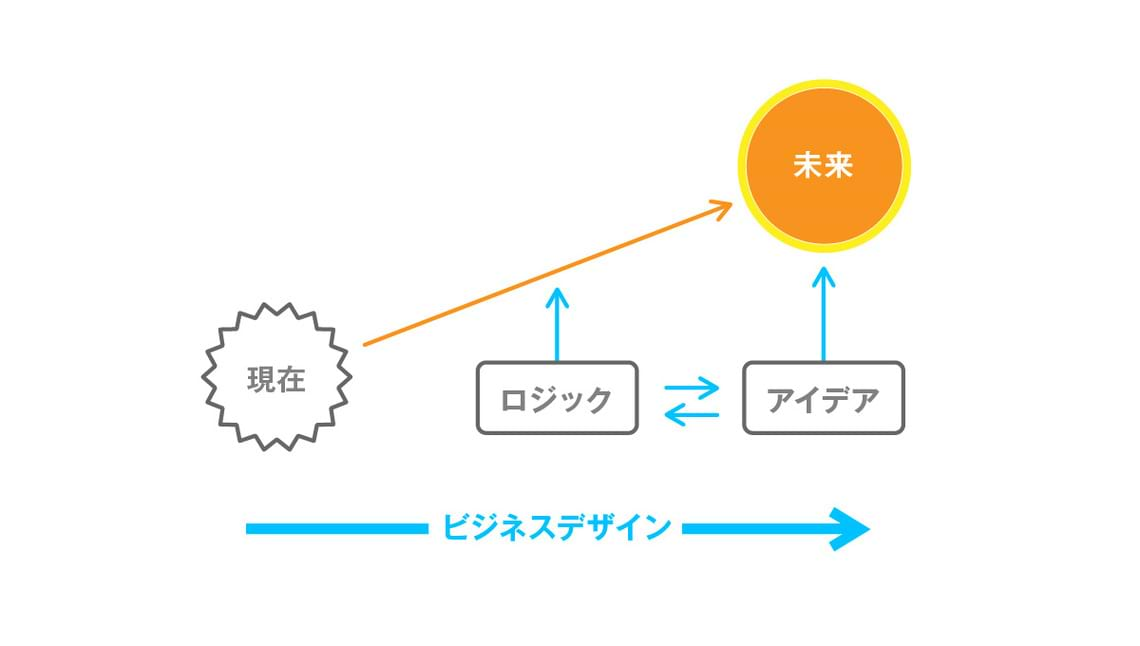

You must develop "business intelligence" – the ability to identify business opportunities in your surroundings by leveraging "analytical thinking" and "business knowledge."

Nami: So, what is the significance of learning through lectures?

Paris: The theories taught in lectures are crucial for understanding past examples (best practices). Understanding what others have succeeded or failed at in business is extremely useful in real business. That's the role of lectures and why we do case studies.

Nami: What kind of environment fosters entrepreneurial spirit?

Paris: We need to create an environment where people talk to each other and give presentations to each other. What we're trying to achieve is making people "comfortable with ambiguity." To do that, we also need to get used to talking to people we don't know.

Nami: At Venture Network every Thursday, entrepreneurs present to investors with a beer in hand. Does the beer also help create that environment?

Every Thursday at Venture Network

Paris: Absolutely. Beer opens people up. Having a beer allows people to speak openly about what they're passionate about. That creates meaningful connections. Investors invest in people, not just ideas, so fostering the best possible encounters is crucial.

Nami: In Japan, it's common to go out for drinks after work.

Paris: That's a good thing. But drinking too much isn't good. It's dangerous.

Nami: Earlier you mentioned that "entrepreneurship involves risk." What are your thoughts on "failure"?

Paris: People learn when they fail. I feel a problem in Japan is that failures at work tend to be seen as personal failures. That's not good.

In the entrepreneurial world, failure is seen as an asset. Even if you've failed three times in business, if you can leverage those failures for the future, investors will fund your fourth venture. As long as the entrepreneur is passionate, failure becomes proof of what they've learned.

People who fail aren't losers. Changing how we perceive failure is crucial.

After this, I also heard about fostering entrepreneurial spirit within large corporations, but since this has become quite lengthy, I will cover that in the next installment.